Metropolitan Opera 2023-24 Review: Dead Man Walking

Joyce DiDonato & Ryan McKinny Shine in Ivo Van Hove’s Messy Production

By David Salazar(Credit: Karen Almond)

The Metropolitan Opera re-opened its doors on Tuesday, Sept. 26, 2023, with a new production of “Dead Man Walking” by Jake Heggie and Terrence McNally.

The production kicks off a major initiative for the company. Last year, the Met announced that due to the success of contemporary works, including “The Hours,” it would invest more potently on newer opera with the hopes of building a new audience. This year, the company is set to feature six operas from the late 20th and early 21st century as part of that initiative. Furthermore, for the near future, only newer operas would open the seasons.

It feels kind of strange to call “Dead Man Walking” a “new opera,” given that it premiered nearly 23 years ago (though if we compare it to most of the works presented at the Met, it is). But the fact that it took so long for the opera, which has been around the globe, to get to the Met stage, speaks to the company’s inability to pivot quickly over the past few decades to keep up with the overall industry at large. Nonetheless, better late than never definitely applies here because “Dead Man Walking” is a special work.

A Complicated Matter

The opera, which is based on a non-fiction work by Sister Helen Prejean and a subsequent award-winning film, features Sister Helen and her interactions with Joseph De Rocher, a man convicted of rape and murder at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola. During her journey as his spiritual advisor, she faces a great deal of pushback and emotional turmoil stemming from the conflict between her faith and morality.

And that’s what makes the opera both rich and complicated. Joseph De Rocher is a murderer and a rapist. It’s very hard to feel anything for him but disgust even though the opera, through Sister Helen’s perspective and how much time is allotted to her attempts to “redeem” him, aims to ask us to try and find some empathy for him. How? By pitting the morality of the situation against another moral issue – capital punishment. I am very much against the death penalty, and the question stands regarding my experience of this work: how should I feel about someone who has committed the ultimate acts of depravity facing systematic execution? That’s where the opera maintains the audience’s attention both emotionally and philosophically. It pushes us to question our limits as humans presenting us with an endless array of scenes full of contradicting arguments and characters.

That serves as both a boon and a problem for the work because it makes it impossible to fully divorce the politics of the situation and our relationship to religion from the piece. If you are on the other side of the spectrum and support the government’s power to systematically execute a criminal, then the issue becomes one of patience with the characters of the opera. If that person is a religious, then it becomes of question of their connection to Sister Helen and the ideals of compassion she is preaching and those inherent contradictions. Conversely, if someone is pro-death penalty and not religious, this work might not be for them. Meanwhile, for those who aren’t religious, it might be difficult to get lessons in compassion for a criminal from someone who belongs to an institution that, in 2023, has limited compassion for marginalized groups.

Regardless of where you stand on this, the fact that opera gets us thinking about these issues as deeply as it does speaks to its importance.

Modern Opera at Its Most Effective

One of the biggest critiques of modern opera comes down to the accessibility of the music. Everyone has a different opinion on this, but personally, music is a universal language because it can connect with us all on a truly visceral level. It stays with us, continuing to work on us emotionally. As I start writing this review, streams of music from this opera keep playing. The opening overture, with its flowing line, is full of tension and foreboding. Then there’s the simple beauty of “He will gather us around.” And most prominently, the gorgeous ensemble “You don’t know” when parents confront Sister Helen about losing their children. The melodic development of that piece is gut-wrenching and simply beautiful. It connects and stays with you. Personally, it’s the musical high point of “Dead Man Walking.”

Heggie’s vocal writing is brilliant in how simple but varied it is. The nuns at large get lyrical, even a jazz-like vocal language, contrasted with the more speech-like quality of Joseph DeRocher; there is no melody in his singing at all, a smart move on Heggie’s part as it makes him the most inaccessible character musically. Contrast that with the parents, who are given voice through song. Meanwhile, Joseph’s mother is a mix of her son’s speech-like lines, emphasizing her alliance with him, but also more lyrical passages that line up with the victims’ parents and show her understanding of their plight. Sister Helen is all of these, her vocal writing altering depending on where she is and who she is with. But most telling is that she opens and closes the opera on an acapella line, “He will gather us around,” a simple tune that gets ample development throughout the opera and further emphasizes her emotional openness as the core dramatically and musically. That we return to this initial seed at the close of the opera, a single voice amidst the void, is heartbreaking.

Meanwhile, the orchestra furthers these connections with De Rocher and the prison associated with darker instruments (and lower voices with the prison guards and warden baritones or basses). As we get closer to his execution, the music’s color shifts accordingly to further emphasize those instruments and sounds. The religious figures are all higher voices, including the dubious priest – a tenor – and are often accompanied by more delicate textures. We see this most prominently at the start of Act two, where Sister Helen and Sister Rose, another nun, sing a glorious duet together. The rest of humanity is a mix, with the quintet of parents all differing voice types. The orchestration there is richer and more varied, best exemplified by the “You Don’t Know” ensemble.

At the center of how this music stays with you is that music is direct and emotional about its methods, a connected whole with musical themes and ideas joining and developing throughout. It is intended for the audience sitting there before them, not a specific one of musicologists or audiences predisposed toward a specific kind of classical music. It’s bare and immediate, and as a result, it is memorable. It’s not about “testing the limits” of the art form, or being different but about engaging with the audience’s expectations, both to challenge them and also to embrace them. Take the ending of Act one. The entire ensemble takes over the stage, and as the orchestra explodes with sound, the entire vocal group starts singing, seemingly improvising anything in the moment; the incoherence of the music works because it coheres with the madness and confusion that Helen is feeling. It’s a traditional choral climax with a bold twist.

Blending ‘Don Giovanni’ & ‘West Side Story’

When the Met announced that Ivo van Hove would be directing this production, I was very excited. I personally loved his “Don Giovanni,” especially when I first saw it in Paris. It was interesting to see how it evolved and adapted to an American audience last season, but I still found it to be insightful and potent.

But when the opera actually started, I didn’t get memories of “Don Giovanni,” but another work I saw Van Hove stage in New York – “West Side Story.” That production didn’t last long in the Big Apple, and for good reason. With the use of live video feed and a massive screen to project that dwarfed the stage performers, that production almost felt like Van Hove really wanted to make a movie but had to settle for theater instead. It cheapened the experience as a whole because it was nowhere near a movie but also not really theater; it was a theatrical Frankenstein.

For his production of “Dead Man Walking,” we got some of the best of “Don Giovanni” and many of the problems that plagued his “West Side Story.”

The set is a massive white box with a few doors that allow the stage flexibility to shift from scene to scene. There is also a large cube hanging over the center of the stage (but more on that later). The real key here is in the lighting and how it is employed to differentiate space. Hope House is characterized by its warmer orange hue, while Angola State Prison is awash in a cold blue. It’s a simple rule, but it’s incredibly effective and perhaps comes to greatest fruition at the top of Act two when we see the two main characters, Sister Helen and Joe, on the stage, but separated by this lighting motif, establishing that the audience in both locations at the same time and allowing for the opening to connect/counterpoint thematically and emotionally.

For most scenes, Van Hove plays it rather safely, relying heavily on the singers’ performances to lead us through scenes, which is especially effective when it’s a two-person or one-person scene. It gets a bit messier, sometimes intentionally, other times not, when there are more people in the room. Case in point would be the best scene in the opera (my opinion) during the appeal hearing. There’s a long table established across the stage that features all the scene’s major players, the parents and Sister Helen. Initially, the rigidity of the scene works for the formality of the hearing. But once everyone has to stand around and wait for the decision, chaos ensues, and the staging goes all over the place. The parents of the two slain children are placed on one side of the stage while Ms. De Rocher is on the other with her children. And yet, because of how massive the stage feels, they all look like bodies floating in a large space without physical anchors. It’s an intimate scene, and the inability of the staging to replicate that amidst the largeness of the space takes away from it. Thankfully, the music is so powerful that nothing else really matters.

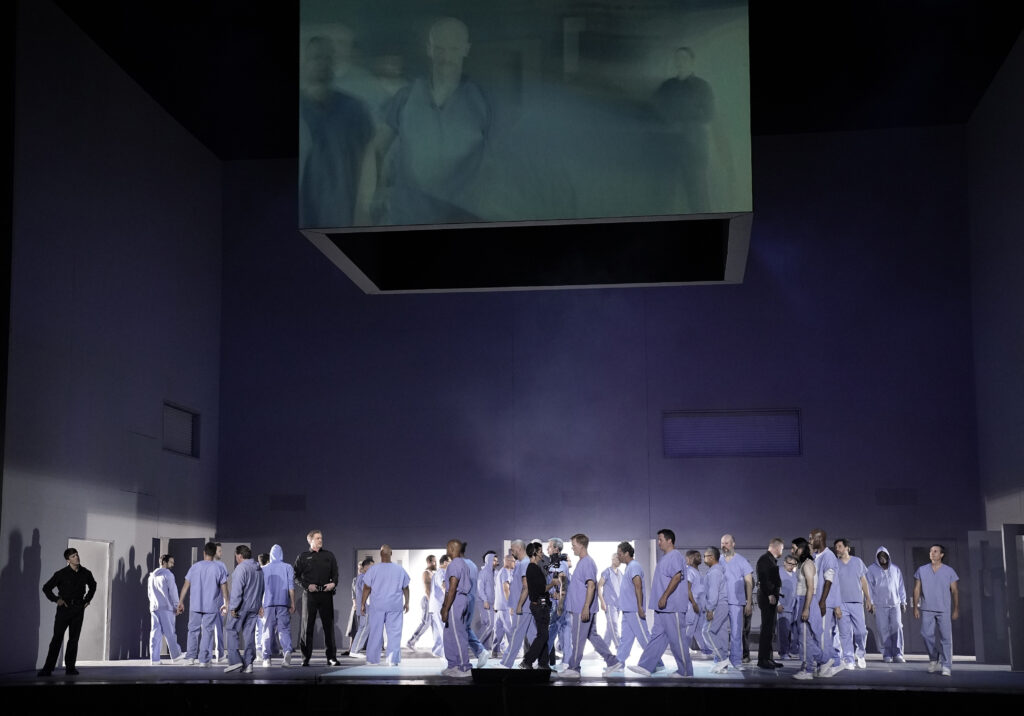

With bigger crowds, it was a mixed bag. Musically it wasn’t always successful with soloists placed upstage and the chorus closer to the audience, thus obscuring the former or forcing soloists to oversing and strain (and throw in the fact that the set was a massive box that didn’t seem to do much for vocal projection to begin with). That said, the actual aesthetics of the staging were more successful conceptually. During the opening scene, Van Hove has the children run and whirl around Sister Helen; that staging is matched and corrupted when she heads to prison and seeks out Joseph for the first time. It’s a potent counterpoint showing us the contrast between innocence and depravity, but all the same, in Helen’s eyes, they are children of God. The first Act ends with a similarly massive choral scene in which the entire cast stands behind Helen, almost as if weighing on her, furthering the impact of her fainting right at the close of the Act. Conversely, the ending, with the lethal injection featuring bleachers, is particularly powerful because it mirrors the audience in the opera house, including us in the act as voyeurs.

(Credit: Karen Almond)

Turning Us into Voyeurs

Speaking of being voyeurs, let’s talk about the use of video in this production.

The opera opens with a short film. The camera flies overhead through a forest. Then it enters that forest before whisking us away down a countryside road and into a bar where we see a a man and woman interacting. We get a Lynchian closeup of a woman before the man rushes out into a truck. All of this over the opera’s foreboding overture. Then the orchestra stops, and some tune starts on the radio, and the film cuts to a couple of young kids having a romantic evening in the forest. The tension builds as we see two silhouetted men arrive then attack them… and all hell breaks loose. We see the crime take place, the curtain rises, and Sister Helen sings her first “He will gather us around.”

Opening the opera with a film is not new and can be a very effective technique. And this one could have been if not for two factors (the second comes up later and needs to be addressed). First off, we have a very particular relationship to film. Modern-day audiences are literate visually and can tell when something comes off as overly staged. The choreography for the murder, unfortunately, felt like that, and no quick editing in the world (which is essentially how they tried to fix this problem) was going to change that. The fact that the film didn’t really line up with the music’s intensity didn’t improve matters. Later in the opera, we get blurred closeups of the girl screaming, appearing as memories and dreams to the main characters. In all honesty, the music tells us EXACTLY what is happening, and a sudden cut to black right as the murder takes place probably would have been more effective than what we got. Less is more, and sometimes having the audience imagine the crime is all the more horrifying than watching one whose staging plays it overly safe. To then have those memory videos come back would likely have been more effective because, instead of reminding us of the staging of the film, it connects us with the dread and emotion that the music gives us.

And as a side note, regardless of whether a production is revived later on with a different cast, it also would have been nice to match up the content/performers of the video with the casting on stage (i.e., it should be re-shootable). Asking the audience to suspend disbelief for one group of parents but not the others is… not optimal in this day and age.

At the other end of the opera is a live video feed of the lethal injection of Joe, which is undeniably the coup de théâtre that Van Hove was likely looking for and delivered. As the staging takes place, a live camera recorded, in closeup, every single step of the way, the images projected on the aforementioned cube hanging over the stage. The entire process is intense and powerful, putting the audience in the middle of the action. It’s kind of ironic to say this, but nothing has ever sounded so unforgettable at the Met than the silence that accompanied this entire scene. Not one note. The silence was deafening – uncomfortably but also viscerally. If I struggled the entire night with my feelings toward Joe and how the opera seemed to want me to feel about him, this moment of intense voyeurism, of participating in the spectacle of systematically executing another human being, transcended that. I didn’t see Joe, but another human. And that was devastating. When DiDonato sang the final “He will gather us around” to close the opera, the effect was just too much to bear.

The Limits of Theatrical Live Video Feed

The problem was that this was the end of the opera, and it felt clear as day that the use of live feed, and by extension, the cube screen atop the stage, was all about this moment and that everything else was reverse-engineered around it, almost as if to justify it all from a production/budgetary standpoint. Because the truth of the matter is that the other instances of live feed were not only superfluous but not necessary. If Van Hove started the opera with a film, interspersed it with a few projections of the crime (or of Sister Helen driving), and ended it all with this live video, it would have been truly powerful. Less is truly more.

But, the inclusion of those other live videos were hit or miss and didn’t cohere at all aside from the fact that they were live video. We get two similar instances during the intros to the prison. The cameras whirl around chaotically as the prisoners enter the stage and then leave. It’s a very brief moment and pure visual chaos. But the chaos is already there on stage, and the camera, which aims to show us Sister Helen’s perspective, is detrimental. The problem comes down to direction. You are asking the audience to choose – watch what’s on stage or look at the screen. On screen, we see Helen’s point of view. But on stage, in the form of Joyce DiDonato’s performance, we also see her point of view. So, which one should we focus on? If we choose the camera, we disconnect from DiDonato’s interpretation. If we stay with her, we might feel we are missing out on this cool new technique that’s just been introduced to us visually, and that must have a point. So naturally, we move toward the novelty, and DiDonato’s work on stage is lost to the audience. We disconnect from the character momentarily.

It gets better the next time it comes around because the camera is shooting at a different framerate and exposure, creating a blurring effect that doesn’t force us to look at the camera the entire time. Once we understand the technique and intention, we can move on from it quickly and see it for what it is – an added effect. But the first instance of live feed is realistic in approach and execution, so it detracts from the impact of the moment.

But the most problematic is the top of Act two. As noted, the staging here is simple but brilliant. De Rocher and Helen are both on stage, lit in different hues to imply their connection/disconnection across time and space. She’s asleep, and he’s awake, and when we shift to her scene with Sister Rose, he sits still, allowing those two scenes to rhyme and contrast emotionally and thematically.

Van Hove adds two cameras and creates a split-screen on the overhead cube, creating a myriad of issues for the audience. The two cameras are set up to film close-ups of the two characters. First off, the duration of a shot creates tension. The tension comes from waiting for the visual payoff, the suspense of knowing where this is leading. Holding on someone sleeping would lead you to wonder if they might wake up at some point. There must be a reason we are being asked to pay attention to this image, as it will most surely have an impact on an upcoming moment. Nothing actually happens until it’s time for her scene, so there is no real payoff to having her shot during his scene and vice versa. One camera would have sufficed.

But of course, the problems multiply because keeping an eye on that image of the sleeping Helen forces us to disconnect from the other of Joe’s monologue, hence why movies rarely do split-screens during a conversation – the directors want us to focus on one particular moment at a time. The problem is multiplied on stage because, since the stage is lit, it implies that the director also wants the viewer to pay attention to the stage action, especially if the camera isn’t capturing it all (it doesn’t and can’t). So as a viewer, you end up confused about what you are looking at. Choice is nice, but the choice here isn’t between following two characters, but which perspective on a specific character we are meant to immerse with – screen De Rocher or stage De Rocher. Because it’s not the same. One is constantly singing and facing the audience creating one interaction. The other is kept in profile by the camera until he looks right into the camera, creating a completely different experience. It’s two different relationships with the audience – in one, he’s interacting with us, and in the other, he’s in partial view until he chooses to look at us (the fourth wall breaking into the camera comes off as jarring as a result). Which one do we interact with? If one wanted to be generous, you could argue that this lines up with how we feel about Rocher – “conflicted.” But then how does it line up with Sister Helen and this sudden split personality? That’s where it starts to stretch credulity.

Then there’s the introduction of Sister Rose. She’s an essential part of the scene, but she’s barely on camera save for a few moments (or when she’s awkwardly in the background of De Rocher’s closeup, which, based on the lighting, breaks the entire intention of the staging). If the intention is for us to focus on the camera images, then her character means nothing to the scene. But if we’re meant to interact with the stage versions, then the live feed is pointless. And when she does get a moment onscreen at the end, it doesn’t add much. We can see that Sister Rose has sat beside Sister Helen and is holding hands. We don’t need a closeup of the hands to understand what it means nor the subsequent two-shot of them embracing. We see it on stage. It’s there for us already.

As I watched these scenes unfold, and unfortunately had most of these thoughts running through my head, I couldn’t help feeling that either Van Hove had no confidence in his staging of the scenes and hence added the live feeds to create more visual “stuff” to contrast the stillness of the staging, or that he was mandated to do more with the live feeds to justify their existence for the final scene (I imagine that HD audiences will get the best experience as the camera feeds will likely be used directly for the video transmission or replaced by them and the visual disconnect from the screen won’t be as big a part of the experience for cinemagoers). Either way, artistically or practically, it didn’t work. And it’s a shame. Because the recipe for success of that scene was already there. The end of the first half of the opera was a coup, and I was excited for it to start up again. This took me right out of it. If Van Hove were to take the video feeds away for subsequent performances, those scenes would be infinitely better with what’s already there. And that’s because the performers deliver those scenes brilliantly. In fact, the performers were the key to the opera’s overall success. I wouldn’t say that they succeeded in spite of the production or staging, but when Van Hove’s direction faltered, they kept me in it.

(Credit: Karen Almond)

Contrasting Stars

The MVP of the night was Joyce DiDonato, who, at this point, is an American treasure. Last season she was the star of “The Hours” and that was no different on this night. From her opening “He will gather us around,” sung with the most delicate and thread-like sound, you were with her. There was both serenity and yearning in her singing, the contradiction perfectly establishing the character’s emotional journey throughout. From there, she sang with ebullience when “He will gather us around” turned into a full-blown choral celebration with the children and Sister Rose before singing with similar brightness and charm during the drive to Angola.

That’s about as long as that cheery nature would last, with DiDonato’s Helen shifting toward increased desperation during her scenes with De Rocher. The first scene pitted the two characters against one another in stark terms, but in the second, where she tells him that “The Truth Will Set You Free,” her singing takes on a more delicate quality, and at one point when he turns to her and acknowledged that he liked that, you could see him visibly shake with hope as she said “Me too,” her singing full of warmth.

One of the standout moments for DiDonato (which is where I double down and say that Van Hove’s decision to bring in the camera at the top of Act was unnecessary) was during the Courtroom scene where Sister Helen is often on the sidelines and gets the brunt of the attack from the parents of the victims. A lot of the time, her back is to the audience, her attention on the other characters. And even then, her body language communicated the conflict. The pain at listening to them and understanding and even siding with them and yet holding on to a conviction that was more than that somehow. It was all there, on stage, in DiDonato’s performance. No need for a closeup to emphasize it.

The same for the top of Act two, where her own moral quandary is at its greatest following a dream. In places, DiDonato was at her most agitated, her voice and articulation of the text pointed. But as Sister Rose comforted her, she settled back into that serenity of the opera’s opening for the sublime duet.

In subsequent scenes, that calm remained even as she begged Joe to speak the truth, and the ending sequences of the opera, in which DiDonato was just asked to listen, were among her strongest moments. It was through her, not Joe, that we were experiencing the horrors. And at those moments, we could understand what it was she was searching for. Having her gentle voice end the opera was a balm to the chilling experience, and even as I write this, I can still hear it. It is going to haunt me for some time.

As Joseph De Rocher, Ryan McKinny delivered a tremendous performance, providing a perfect counterpoint to DiDonato. His voice has a thick and earthbound quality that suits the character. With his imposing stature and gait, a rigidness in his early appearances matched his unyielding stance on the truth. He sang with a dark, direct, and often jagged line, making him completely unapproachable. But then the opera allowed for moments of warmth, such as the second scene with Sister Helen after he finds out that he is to be executed. When he repeats, “The Truth will set me free,” his voice takes on a thread-like quality that matches DiDonato’s similar prayer-like phrasing.

McKinny’s opening monologue in the second act is a unique exploration of the character, allowing him to reveal his feelings about his impending execution. In the production, McKinny does pushups and then sits and sings to the audience, occasionally turning to the camera. While McKinny’s singing was powerful and potent, it was hard to connect here, mainly because of the camera issues stated. McKinny has a solid camera presence, which I witnessed in the scant moments he got here (especially the ending scene) and from past work he’s done. But asking him to play to the camera and theater audience simultaneously is a challenge for any actor, and his looks to the camera, which picks up the most subtle of details in closeup, came off as distracting and off-putting (not in the right way). It hindered the quality of his overall excellent performance.

That said, as the story moved closer to its climax, McKinny imbued Joe with greater vulnerability, particularly during the scenes with his mother and brothers, his confession, and the ending. The gruffness of his voice developed into a more delicate tone that coalesced with DiDonato’s. When he finally reveals the truth, McKinny’s De Rocher sits down, his legs close to his body in a child-like position, delivering the narrative of his crime with increased agitation. When he utters his last words, in that final moment, McKinny portrays a man full of fear with hushed utterances.

Other Standouts

Susan Graham gave one of the night’s standout performances, especially when she appeared before the appeals board and made her statement. Her voice sounded weak and muted at the outset, emphasizing her anxiety in the moment. But as the scene developed and her desperation grew, her singing did as well, exploding with tremendous strength at several moments as she pleaded for her son’s life.

As Sister Rose, Latonia Moore’s soprano shone in the space, particularly during the Act two duet, where her smoother sound complemented DiDonato’s more anxious tone.

Chad Shelton provided comic relief as the snarky Father Grenville, his voice pointed in its delivery. Being the first line of conflict that Helen faces in the opera, his sardonic delivery provides a fitting change of tone. Meanwhile, despite his darker tones, Raymond Aceto had a rounder quality that counteracted Shelton’s interpretation in the previous scene, amplifying the work’s musical and dramatic qualities.

As the victims’ parents, the Harts and Bouchers, Rod Gilfry, Krysty Swann, Wendy Bryn Harmer, and Chauncey Packer sang beautifully as an ensemble. The fact that their vocal qualities were so different allowed each one to stand out among the vocal ensemble. Gilfry’s character arguably gets the most prominence here as he lambasts Sister Helen most profusely at the start and then essentially reconciles with her at the end. Gilfry developed this brief arc, his singing stern and aggressive in the first scene but softer and rounder in the latter scene.

The opera also featured a larger ensemble of performances by Christopher Job and John Hancock as prison guards; Justin Austin as the Motorcycle Cop; Alex Jarvis as Mrs. Charlton, Briana Hunter as Sister Lillianne; Helena Brown as Mother; Jonah Mussolino and Mark Joseph Mitrano as Joseph’s brothers; Patrick Miller, Jonathan Scott, Earle Patriarco, Ross Benoliel, and Tyler Simpson as Inmates; and Regan Sims as a Paralegal.

In the pit, Yannick Nézet-Séguin led the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Newer music is his strong suit, and here was no different as the orchestra sounded at its finest throughout the night. The overture of the opera was a major standout. There were some moments with the ensembles that sounded a bit messy, with balance a bit all over the place, though personally, I think this might have had to do with the staging more so than the musical execution overall. When the soloists were closest to the front of the stage (at the end of Act one), the balance was cleaner and tighter.

Pacing is always key to newer works, especially since they have more scenes than more traditional ones, thus more of a musical and tonal shift. Nézet-Séguin has always excelled in this particular aspect of modern opera and definitely nailed it here as well as the opera moved at a solid pace, never lagging.

While the production leaves a lot to be desired, it’s impossible not to appreciate the big swings it takes. More importantly, it’s the vessel through which a work like “Dead Man Walking” and its amazing cast are allowed to take the Met stage. And that’s the key here. This is the season that Met Opera management has decreed as a shift in direction, and this is the first statement of intent. It’s a solid one.