Metropolitan Opera 2021-22 Review: Fire Shut Up in My Bones

Terence Blanchard & Kasi Lemmons’ Masterpiece Makes History in So Many Ways

By David Salazar“You gotta disturb the earth to make it grow.”

Uttered by Charles Blow’s uncle Paul in Act one of “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” that line means so much in the context of this work, our world, and on Sept. 27, 2021, the opening of the Met Opera’s 2021-22 season.

First up, this was a historic night. Terence Blanchard and Kasi Lemmons’ opera, based on the autobiographical book by Charles M. Blow, was the first by a Black composer in the Met Opera’s history.

Then was the added context of this opera being the first official performance at this theater since a global pandemic literally rocked the world by shutting it down.

And then there’s the fact that, in the context of looming social questions about race and equity we have more openly grappled with during the lockdown, opera is in a struggle with its own identity and how to move forward. The Met itself is in many ways ground zero for the conservative mindset – a place where a large portion of its audience clamors for tried-and-true classics while barely showing up for newer works past the opening night curiosity. A place where many of these audience members have vociferously expressed their disdain for productions that dare to challenge them, forcing them out in lieu of safer, more tepid versions (see Willy Decker’s “Traviata”).

A place where there would undeniably be questions over the staying power of something like “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.”

But now a place that, on the evidence of opening night, must realize that this opera “disturbed the earth” and will hopefully kick open the doors for a more diverse operatic repertory for years to come.

Disturbing the Earth

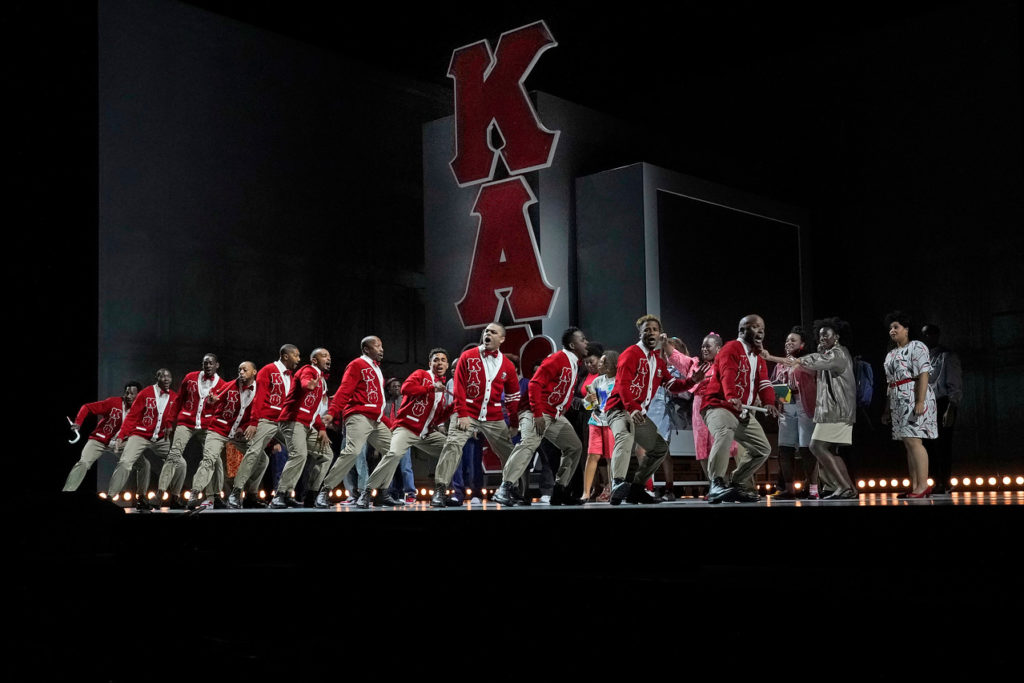

Let’s set the scene at the start of Act three. The curtain rises on a massive Kappa Alpha Psi emblem as the fraternity brothers, portrayed by a troupe of dancers, make their way onto the stage. Everyone who saw the videos the Met shared online prior to the opening knew what was coming and they greeted the dancers with exuberant applause. But even then, they could never have anticipated the sheer mastery that would unfold through Camille A. Brown’s choreography. And when the dancers had completed their number (no orchestration by the way to accompany them – they were both dancers and the music), the entire audience JUMPED out of its seats to give them a standing ovation.

Now, I’m not old enough to have gone to the Met during the halcyon days of its glory years in the mid-20th century. I don’t know if the likes of Birgit Nilsson, Franco Corelli, or even Maria Callas got show-stopping standing ovations in the middle of a performance. But I do know that I have never seen that in recent history. Ever. I’ve seen anger and walkouts during performances (“Death of a Klinghoffer” comes to mind), but never the sheer excitement, joy, and celebration on display during this particular moment.

But what’s most essential to remember is that it came from a moment that we never see in most opera houses – a moment where the orchestra, the vocal soloists, the chorus were part of the audience. A moment where dancers were not performing classical ballet. It came from step dance.

This got the audience out of their seats and stopped the show.

Which simply goes to show that opera audiences can crave more than vocal pyrotechnics from the great classics. They crave a deeper connection. A feeling that opera can be fresh.

And surprising.

And truly inclusive of other cultural experiences.

And that’s not to say that the bravura of “Lucia’s” mad scene or the vocal endurance feats of Wagner’s epic poems no longer has a place or ability to wow us at the opera house. Of course it does. We must continue to build on what’s come before.

But what it means is that opera has more room at the table. In fact, it needs a bigger table with more seats and permanent places for all kinds of people. Not just a one-time invite. And we most certainly need that table now at the Met, with its gargantuan 4,000 seat theater and long-held status as the leader of the opera world.

But “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” in my mind, is a triumph not only because of what it represents in a larger social context or how it can open opportunities for future creators of color but because it is itself, a masterpiece.

(Credit: Ken Howard)

Peculiar Grace

Charles Blow is a boy with “peculiar grace,” ridiculed by many, neglected by his parents, leaving him vulnerable to the attention of his predatory cousin Chester, who seizes on Charles’ loneliness to abuse him. Years later, Charles seeks out a means of overcoming this trauma through numerous rites of passage (baptism in church, sex, college, joining a fraternity, and even a romantic relationship), ultimately finding that none of them can truly heal him from those wounds.

Meanwhile, he is forced to contend with the forces of toxic masculinity with constant reminders from male counterparts (and even women) around him that men don’t wear their hearts on their sleeves. Men don’t talk about their pain and trauma. Instead, men just hold it in, puff their chests, look strong, and take what they want (and worry about it later).

What’s shocking about this exploration of manhood in “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” is that it spotlights so many of the operatic heroes of the great classics. Time and again we see men in opera follow their emotions more than reason and, quite frankly, common sense; they tend to “take what they want” and “worry about it later.” But instead of glorifying that archetype, “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” openly questions it. Time and again, Charles tries to fit in with this “ideal” of manhood, only to find himself unsatisfied and increasingly frustrated and angered.

But the opera doesn’t only seek to break down the male archetype in opera, but also take on opera’s inherent misogyny head-on. For despite the Met Opera’s questionable decision to only focus on Will Liverman (who plays Charles) in its marketing, this is also the story of his mother Billie (played by Latonia Moore) and her own travails in this toxic society.

In fact, as structured by Lemmons, the first half of the opera is all about Billie. Sure, we open up with Charles at a crossroads as he prepares for vengeance, but then we flashback to his childhood where his mother takes centerstage. We see Billie struggling to raise five boys, working in a chicken factory, dealing with her conniving and irresponsible husband Spinner, and simply trying to overcome her own sense of loneliness. At one poignant moment, she reflects on how it’s impossible to feel alone in a house full of people before noting that she does in fact feel so alone in such a place.

And it’s this loneliness, like young Charles’, that leaves her vulnerable to her husband returning to her life time and again to do the same over and over. It’s a perpetual cycle in which the victim is repeatedly abused even though they want to “leave it on the road” and move on.

And when faced with this disgrace, Billie’s choice is to pull out her gun and threaten Spinner and the other women with violence. It’s no surprise then that at his own breaking point (or bending point, as the opera ultimately shows), Charles also thinks that pulling out his mother’s gun is the solution to ending his problems.

Of course, what the libretto reminds us of is that the violence never does anything for Billie. She pulls it out at the midpoint of Act one only to have to do the same thing later in the act. But it doesn’t relieve her pain. She eventually “leaves it in the road,” though not without difficulty, and gives away the gun, to her son.

Charles comes to this very realization as well at the climax of the opera and also eschews that very symbol of perpetual violence and pain. And it’s fitting that the opera ends on a note of connection for the two characters as they openly express their love for one another, something each was incapable of doing at earlier moments (Billie at the end of Act one and Charles at the end of Act two).

That’s just the two main characters. Circling them is an entire world of foils and doubles, starting with the embodiments of Destiny and Loneliness that follow and guide Charles as he reflects on his life. Loneliness reminds him that she’s all he really has while Destiny reminds him of the inevitability of his fate. No doubt that when Charles wonders about his culpability in his trauma, these two muddle the message and seem to push him toward tragedy. It is worth noting that these embodiments are unique to the opera itself and not directly taken from the original book on which the opera is based. Destiny / Fate and Loneliness are time-honored tropes in opera and seem to imply that Charles might be headed toward a typically violent operatic conclusion; that he doesn’t further this dialogue that Lemmons and Blanchard are having not only within their own work but also with the art form itself.

While Destiny and Loneliness are portrayed by a woman, they find male counterpoints Spinner and Chester. Spinner represents the loneliness that Billie is subjected to. He is a terrible husband by any standard – philandering, deceiving her, taking her money, and never providing for his family. He claims that he’s given her everything he has and even the things he doesn’t (his dreams), but the truth is that he is barren and empty.

Chester is an embodiment of Destiny for Charles and the inevitability of his trauma; the idea that within the world he was born into, there was no other possible outcome than for someone to come in and abuse him in this way.

This notion is furthered by the mythical passage of the “boy with a peculiar grace” that crops up three times in the opera. The first time this myth comes into play is precisely when Charles is first abused. And who delivers it? Destiny. The passage / myth emphasizes the inevitability of Charles’ fate, the pain he’d suffer in a place like the South. And while we’re on the subject of myth, these abusers tend to use God and redemption for the sinner as a means to justify their ends.

Both Chester and Spinner are juxtaposed with the soulful character of Uncle Paul, who imbues Charles with the simple philosophy of disturbing the earth to make it grow. This concept of connecting with not just the earth but our own individual nature is furthered by ideas of roots running deep and furthered by the whole notion of bending but not breaking, which is ultimately embraced by both Billie and Charles.

This is but a scrape of the surface of a nuanced and complex libretto that warrants revisits for deepened experience and understanding.

Musical Storytelling

A common complaint leveled against modern opera (and often rightly so) is how distancing it can feel. A lot of modern composers, despite their best intentions, tend to fall into the mistake of being too clever for their own good. There’s nothing wrong with trying to challenge your audience, but when being a musicologist is almost pre-requisite for understanding the nuances of your score, then the opera is not for any audience, but a specific one. That’s one of the reasons why opera gets the brand of being elitist.

Terence Blanchard doesn’t seem interested in making this kind of opera. While there’s no doubt that his “opera in jazz” is full of nuance and details that will undeniably cater more to certain audiences (all opera does in some way), this work’s music is, like its libretto, in open conversation with the art form’s history. There are ample solo numbers that one can identify as ariosos with lush vocal lines and sublime orchestration. There are shifts into more rhythmic fare as well as moments that play to the jazz quartet’s strengths. But it always connects to the dramatic moment in a very visceral way.

One moment that stands out to me is the myth of the “boy with peculiar grace.” In its first iteration, it’s a sublime bit of vocal writing underscored by menacing accompaniment in the strings. When it returns in the second Act, there’s a more serene quality to the music, with a similar vocal passage, but a different character in the accompaniment that gives the audience a feeling of change and even transcendence. But when it returns in the third Act, transformed with a more rhythmic and angular quality, it feels like all that which was gained has been lost.

It’s this kind of musical storytelling that not only more clearly tells the story, but more readily immerses us in it. And “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” is replete with it.

(Credit: Ken Howard)

Immersive Detail

Speaking of immersion, this complex libretto and score were brought to life in a glorious production by James Robinson and Camille A. Brown that is arguably the best use of projections in recent Met Opera history. Whereas past productions have tried to play up the use of projections the way movies of the past have tried to show off their CGI (see LePage’s “Ring” Cycle) to diminishing returns, this one is conservative in its approach, eliciting a far more satisfying experience.

The projections along the perimeter were mostly utilized as scene-setters, shifting the perspective between scenes, and allowing for a seamless, almost cinematic experience. At center stage were two cubes used in varying formations depending on the necessities of the scene. In one moment they were used to portray the home of the Blow family. In another as the abandoned house in the woods and later on as the college campus. Never obtrusive or overbearing, this stripped-down aesthetic allowed for us to focus on the music, the words, and the performances on hand – the essence of opera.

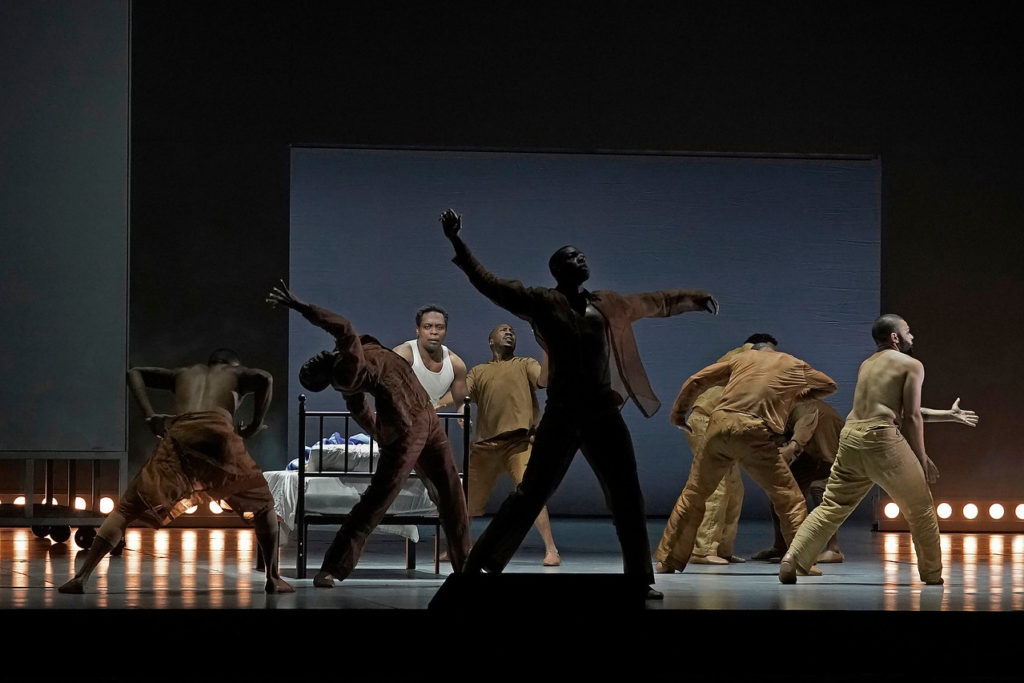

In keeping with the mirroring and doubling structure throughout, Robinson and Brown also employ a number of pivotal visual mirrors in their direction. The most notable are the two bedroom scenes – the traumatic abuse by Chester with a projection of young Char’es face on one of the large screens, and the love scene between Charles and Greta in the third Act. Narratively, both scenes could not feel more different; but both connect in numerous ways. Dramatically, they both represent heartbreaking moments for Charles and pivotal turning points. The first is the traumatic experience that will mark his life while the latter sets him on the path to vengeance and eventually redemption.

But the latter scene with Greta is the very moment where Charles finally reveals the details of what happened in the former scene and thus its connections to it are all the deeper thematically. When Charles finally reveals this experience to Greta (and the audience), it’s this moment of intimacy where he seemingly loses her and realizes he won’t find fulfillment or healing through her.

It’s also worth mentioning the visual expression of the sexual acts in these two scenes. Both feature the two main players stripping down and Greta and Charles fully embrace one another; we never see Chester’s abuse of Char’es, nor do we need to. But in some ways, it makes it all the more horrifying, as it forces the viewer’s imagination to put the pieces together, something we most definitely don’t feel comfortable with.

Then there are more subtle doublings and mirrors, such as how Chester and Spinner are portrayed. As directed, the two men enter from the same place at the close of Act one, are both dressed in similar attire, and are even confused for one another at one point. One could even go so far as to say that when faced with violence from those they abused, the two are also portrayed as cowards who run off with “their tails between their legs.”

There are also some rapturous passages of ballet (in addition to the aforementioned step dance) of male spirits seemingly haunting Charles as he comes to grips with his experience. They dovetail nicely as disembodied contrasts to the spirits of Loneliness and Destiny that also haunt Charles.

This detailed work gives the overall opera a sense of sublime cohesion that makes the experience immersive and transformative.

The Search for Redemption

The pivotal role of Charles was played powerfully by both Will Liverman and Walter Russell III (taking on the younger incarnation of the character), allowing for poignant contrast in both the physical and vocal interpretations, especially when they sang together in duet (another creative and astute choice by Blanchard to immerse us in Charles’ experience of his life in the present and retrospectively). Where Char’es-Baby skips onstage in his initial appearance, the older Charles runs at the audience, gun in hand. Where Russell III’s delicate, vibrato-less voice beautifully expresses his innocence and “peculiar grace,” Liverman’s rugged baritone allows for greater layering and complexity. While he takes on a more supporting role throughout the opera’s first half, his major interjections, which bookend Act one, are full of anger and pain. As the act concludes, Liverman’s Charles repeats the lines “It never dies,” his voice almost a visceral weep at first before “dying” away. These final bars have a haunting effect, the diminuendo akin to a fade out without necessarily having a feeling of musical resolution.

It sets up the second half where Liverman’s Charles takes central stage. Here Liverman’s baritone takes flight as we see a gentler, more exuberant side juxtaposed with moments of yearning; this is most notable in a second Act arioso where he reflects on his loneliness. But as Charles seemingly finds his way further and further away from his trauma (he grows up, goes to college, meets new people, finds love), Liverman’s singing takes on a more tranquil and serene quality, suggesting Charles finding some sort of inner peace. We can see this most prominently in his recitation of the myth of the boy with “peculiar grace,” which appears after his first sexual encounter as he prepares to “head North.” At this point, Charles believes he’s overcoming his trauma and Liverman’s legato line is pure and gentle.

But upon having his heart broken by Greta (again, Liverman’s pained singing here called back to the final enunciations at the end of Act one), the anger and fury makes a comeback with a vengeance (and some powerful and robust high notes). During the final recitation of the myth of the “boy with peculiar grace,” Liverman’s singing took on a more jagged quality, emphasizing his self-loathing. This hostility was furthered with the return to the opera’s opening scene where Charles finds himself at a literal crossroads as he prepares to murder Chester. Liverman’s tortured singing comes to a head, especially when confronted with Char’es-Baby’s final reappearance as he reminds him that sometimes you have to “leave it on the road.” It’s in this moment where we fully feel the contrast between these two versions of Charles, both physically and musically. Both Liverman and Russell III combined to create a nuanced portrait of Charles, allowing us to see his journey from innocence to deep trauma and back to healing.

As Billie, Latonia Moore nearly runs away with the show (she pretty much did during the Met’s last opening night when she appeared as Serena in “Porgy and Bess”). In some ways, she is the recipient of some of the most challenging music in the entire score. She’s called upon time and again to shift from glorious long legato passages to more pointed and rhythmic material, this musical push and pull a clear reflection of her character’s own struggles in a world that constantly asks more and more of her. Moore’s voice was a constant beacon throughout, always clear and resonant in the space.

What was most refreshing about this particular interpretation is how complex the role and Moore’s interpretation proved to be. Yes, we sense her in anguish throughout and we see her fury when she pulls out her gun on several occasions to fight back her philandering husband Spinner. But we also see her flirtatious side (again with Spinner) as she tells her boys to watch “Big Foot” on TV while “daddy goes to help me with something.” We hear her hopeful side as she sings of being a teacher someday. We feel her tender side as she asks Charles to stay close by so they can go to school and study together. And we even lament moments of her neglecting her own son as he asks for her to tell him she loves him. Moore manages all of these differing beats seamlessly and it’s not out of step to say that with Billie, she has delivered one of the most complex interpretations of any character on the Met stage in recent history.

(Credit: Ken Howard)

Creating the World

Angel Blue also makes her presence felt in the three distinct roles of Destiny, Loneliness, and Greta. Her interpretation of both Destiny and Loneliness are of particular interest with regard to the vocal contrasts. She sounds and moves almost like the snake in the garden of Eden when she approaches Charles in the abandoned house in Act two, reminding him that no matter what happens, “loneliness is always here.” She seems to revel in his pain, her voice taking on an earthier and rougher edge. There’s an excitement as she watches him run off with Evelyn for his first sexual encounter.

Contrast this with Destiny, who comes off as more sarcastic in her first and last entrances, almost seemingly laughing off Charles’ laments, and reminding him that he can’t escape his fate. But when she appears at the end of Act one to witness Chester’s abuse of Char’es, her interpretation of the “boy with peculiar grace” is issued as a lament. Blue’s voice here is gentle, almost disembodied, highlighting how Charles later describes the incident and his own experience of it.

When she reappears later as Greta, Blue’s overall characterization is an amalgam of those other two roles. She’s flirtatious, aggressive, and yet gentle and loving in the final moments with him.

Of particular note were the two artists enlisted for the characters of Spinner and Paul who represent the heart of the conflict of Charles’ understanding of manhood. Not only are these characters distinct in their musical approaches (Paul’s legato lines coalesce with the grounding philosophy he imparts on Charles while his father’s more rhythmic scoring suggests his instability and always being on the move), but the casting in this particular case is pure gold. On one hand, you have Ryan Speedo Green as Paul with his round, earthy bass that feels like a big aural hug every time he pours it out into the auditorium. And on the other, you have Chauncey Packer with a light tenor that feels flighty in this music, his singing prickly and almost against the grain. Green’s Paul is shown working the land and being a family man; Packer is interrupting work and making moves.

As mentioned, the character of Chester is a double for Spinner, so it is no surprise that Chris Kenney, in his Met debut, hews hauntingly close in his interpretation to Packer’s with a similarly snake-like vocal personification. Even some of the physical ticks, the way they walk, and even their cowardly expressions as they prepare to run away match up rather well, furthering this connection. But what Kenney also adds a sinister layer, particularly in the moment where he strips down and circles young Char’es, staring him down as he goads him into “playing a game.”

We see other similar doublings in interpretations of Evelyn and Ruby, interpreted by debutantes Brittany Renee and Briana Hunter, respectively. Both masterfully ooze vocal and physical sensuality in their respective moments, the former with Charles and the latter with Packer.

Then there’s the larger bands of brothers – Billie’s other four sons (in their younger and older incarnations) and Charles’ fraternity bros and their hazing, another form of abuse. The former group, (performed initially by Cheik M’Baye, Oeode Oshotse, Ejiro Ogodo, and Judah Taylor, and later by Calvin Griffin, Terrence Chin-Loy, Errin Duane Brooks, and Norman Garrett) is in contrast with itself. The younger incarnations never sing, their “voiceless” nature relegated to the background of the drama between the older characters. But when they return in the second half as older incarnations, they prove to be the new messengers of toxic masculinity, only interested in their brothers’ sexual rite of passage but intolerant of his need to express deeper sentiments. While the younger versions never really share any dialogue or sing together, this older incarnation is like a well-oiled machine, singing in harmony – a callback to the initial male chorus that critiques young Char’es for his “peculiar grace” and the drilled-in indoctrination of how a man should act.

The same goes for his fraternity brothers, who do more dancing (and beating) than singing and when they do vocalize their thoughts, they are, again, chanting as one. The choice to express them as step dancers, more than a further exploration of cultural nuance, also adds both contrast and similitude with other male-dominant groups in the opera. They retain their own individuality as a unit, but they are again, of a singular mindset.

In the pit, Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin, sporting a colorful jacket, led a solid performance of Blanchard’s score. There were some initial balance issues in the opera’s opening moments, but after a while, there was a consistent ease with which he led the show. From the orchestra seats, voices came through clearly as did the differing colors in the pit. The jazz quartet also got ample opportunity to shine, blending seamlessly with the other orchestra colors throughout.

The chorus also put in a formidable shift throughout the evening, particularly in moments where they were tasked with accompanying the soloists (Charles’ Act two solo comes to mind).

I cannot emphasize how unforgettable an experience this was. There was always going to be a vibe in the air given the context of the performance and people’s craving for this kind of artistic experience for more than a year-and-a-half. But “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” transcended even that. The opera itself, finding healing from trauma through communication and love, was in so many ways a perfect encapsulation of our own collective experience and needs.

There are seven performances left of this opera in the 2021-22 season. After that, one hopes that the Met does its job and gives it a permanent seat at the table because Blanchard and Lemmons’ masterpiece deserves that and so much more.