Metropolitan Opera 2019-20 Review: Wozzeck

An Overwhelming Experience With Little Payoff & an Underwhelming Performance by Peter Mattei

By David SalazarOne could call the Met Opera’s new production of “Wozzeck” a collage.

The opera itself undeniably brings this word to mind in how Alban Berg unites the dark tale of a misanthrope who murders his lover and drowns himself via numerous musical structures and forms. The entire first act features a suite, a rondo, a lullaby, and a passacaglia while Act two is essentially a symphony in its four movement structure; the final act is a series of inventions on single notes or rhythms or chords, etc.

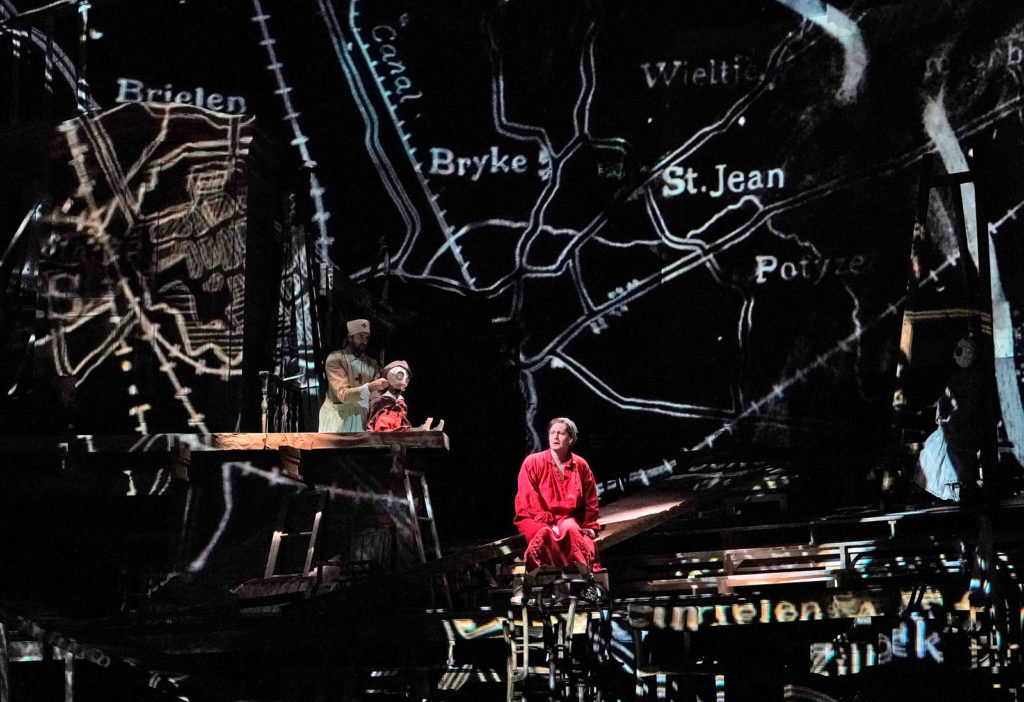

And as such, William Kentridge and Luc De Wit’s production, making its Met premiere, throws together a wide range of imagery that combines both surrealism with gritty realism to create a panoramic view of the story’s society with literally one set that constantly morphs and shifts into different locales.

Companion Piece

In many ways, this production is the perfect companion to this opera in its complexity and ability to pack so much information into such a small space (the opera does much the same with all of the unique musical structures in less than two hours of music).

As the opera opens, we see Wozzeck himself engaged with a film projector and a small screen in the middle of the stage showcasing a variety of images that fly by before you can really grasp their meaning. Eventually the projector will simply take off on its own; there is also a massive screen upstage that dovetails with this one to project the same images in addition to a few others. This is but one visual element in a parade of others. Marie’s son wears a white mask that almost makes him look alien; throughout the performance, choristers can be seen in a similar mask, providing a stark contrast to Wozzeck and his own sense of alienation.

The entire set is broken up into different sections that allow for the piece to move seamlessly from scene to scene without distraction. In the middle of the stage is a table with a nearby doorway that acts as Marie’s home. In the upper section of stage right is a small alcove of sorts that is used for scenes with the doctor as well as a performance space for several musicians.

The lighting design by Greta Goiris also plays a major role and, in some cases, particularly during Wozzeck’s death scene, one simple switch suddenly changes the entire set completely. It’s this flexibility that gives the production a sense of connectivity and forward movement.

And while the design and direction has the major advantages of a collage in its ability to pack a lot of information in a limited space, it also features many of its drawbacks. While you can get the big picture on first viewing of a collage, you can’t really take it in all it has to offer unless you really take a closer look at the individual details. This is undeniably the case with this “Wozzeck.”

You definitely come away with the feeling of depravity in the work; you feel the hardship of the impoverished world that Wozzeck and his community lives in; but it all flies by so quickly that you can’t really take in all of the other grace notes and symbols layered throughout. While this is a short opera that packs a lot of action in its short span, Wozzeck does allow for moments of reflection where you can engage with some of the philosophical and emotional discourse taking place between the characters. The previous Met production, with its minimalism, undeniably allowed for this kind of interaction with the opera.

But in this new Kentridge-De Wit take, the sensory overload is so great that you can’t really tell where to concentrate. As noted, the video projections are on two screens and even if some of the footage is on loop, you are drawn to it and trying to understand its meaning; this takes the viewer away from the action relating to the singers. And if you aren’t a native German speaker, good luck trying to keep two eyes in three places because every sentence in this opera is packed with meaning.

The reality is that when you walk away from this production, you feel like you missed out on most of the experience and this nagging feeling that you definitely need to go see it again to get more out of it. To be challenged by a work of art is never a negative, but this production leaves you cold emotionally and probably confused intellectually.

(Credit: Ken Howard / Met Opera)

An Abyss

That doesn’t include the fact that you still have a lot to listen to, especially in a complex score like “Wozzeck.”

Maestro Yannick Nézet-Séguin seemed to be operating on polar extremes of intensity with the orchestra either super charged or rather subdued, giving the performance a sense of predictability. The music didn’t seem to be driving the drama so much as it was simply there as a consequence of it.

His work with the singers was very up and down. In many instances, particularly at the start of the night, the conductor drowned out a few of the major singers. Inversely, he was also a solid companion to Elza van den Heever’s Marie during the prayer during the first scene of Act three.

He did however have some stellar moments, particularly the massive crescendo during the Invention on a single note where the orchestra was as thunderous as it has probably been all season; that said, he moved quickly through the passage, its lingering impact diminished as a result.

In the title role, Peter Mattei sounded overpowered early on in the opera, but eventually found his footing, his splendid baritone ringing nicely in the hall. However, his interpretation of Wozzeck didn’t really provide much depth or complexity, his singing lacking the edge or grit that adds to the devastation of the character.

Mattei is an elegant singer with a voice capable of some truly searing emotionality, whether it be in Mozart or, especially in Wagner’s “Parsifal,” but here, the fine qualities of his voice undercut the character’s pain and suffering. It was technically sound, but rarely pushing a complex color palette that could provide strong range of emotional weight to the character. One might suggest that it all sounded rather restrained throughout, which might bode well at the start of the opera, but certainly doesn’t add tension as the character starts to unravel. When accused of murdering Marie, Mattei’s vocal expressions during the ensuing scene, “Das Messer? Wo ist das Messer?” lacked the desperation and fear that the character claims to have, his singing rather similar in expression and approach as in previous scenes. As such, the character felt static even though the story clearly pushes him to a breaking point where his next action is to commit suicide.

No doubt that this music is probably the most complex Mattei has performed at the Met to date and this could all be chalked up to being the first performance. As such, it should be interesting to see how his interpretation develops over the course of the run.

Scene Stealers

It didn’t help Mattei’s cause that his performance seemed to be overshadowed by his colleagues in virtually every scene. To a certain extent this might be the point and reflects the story at large; but at some point, “Wozzeck” requires the central character to take hold of the drama and become its emotional core. In this performance, that honor belonged to Elza van den Heever’s Marie as the soprano managed to portray a character full of complexity and contradiction. She was gentle in her expressions toward her son, but in her confrontations with the Drum-Major, she was assertive and aggressive. She resisted his advances before seizing control of the situation, blasting out intense sound as she pushed him into the room for their first sexual encounter. In a latter scene, she made the Drum-Major chase her. Her scenes with Wozzeck hinted at a combination of fastidiousness but also tenderness, while her shining moment at the start of the third Act allowed her to express her deep fear and inner turmoil.

It was during this particular moment where van den Heever, after a number of scenes showcasing a bright and vibrant sound, suddenly pulled back and allowed for something far slenderer and more intimate. When she yelled “Fort!” at her son, her voice cut through like a jagged knife in one of the viscerally pained moments of the evening. But right after, she pulled back to the tender vocalism that had commenced the scene, giving it a great sense of external and internal tension; she was afraid of what Wozzeck might do, but was also struggling with her conflicted emotions toward her son.

As the Captain, Gerhard Siegel dominated the stage with a brilliant tenor and some truly mesmerizing high notes. Christian Van Horn, as the doctor, also displayed some exciting comic chops in his scene with Mattei, though his sound occasionally got drowned out by the orchestra. Tenor Andrew Staples, in his Met debut, had a solid night, displaying truly confident singing in his upper range during the second scene of Act one.

As the Drum-Major, Christopher Ventris sounded a bit overpowered as well and his sound was somewhat muffled and lacking in bloom. However, he made up for his vocal limitations with a very virile display that focused on intense machismo and physical showboating. His flirtation with Marie was very sexually charge and awkward, while his bullying of Wozzeck at the end of the second act was truly revolting. He went from egging on the central character to physically abusing him as the situation intensified.

As Margaret, Tamara Mumford delivered a pointed performance, mopping up the floor while hurling jagged vocalism at Marie during “Was Sie, Sie ‘Frau Jungfer!’” She was similarly despondent during her latter interaction with Wozzeck, though her accusations, which are written in the lower register of her mezzo-soprano, didn’t quite pack a resonant punch and sounded rather muted.

Overall, it is truly challenging to assess this evening. In many ways, the sensory overload that you experience throughout is exactly what you might want from a night at the opera. And yet, with such a challenging work, the delivery of this production makes it very difficult to interact with the opera on an emotional and intellectual level. You constantly feel like you’re trying to keep up with a fast-moving train. On some level there is an understanding that this is a ride you probably have to take again to get more out of it. But the first trip might leave you so drained and lacking in payoff that you might not want to.

Categories

News