Metropolitan Opera 2019-20 Review: Agrippina

Joyce DiDonato & Brenda Rae Are Dominant Dueling Divas In David McVicar’s Masterful Modern Take on Handel’s Political Comedy

By David Salazar(Credit: Marty Sohl / Metropolitan Opera)

The operas of Handel are not necessarily standards at the Metropolitan Opera. And to a certain extent, that is understandable. They are rather expansive in runtime with ample casts and a musical style that doesn’t always suit the cavernous hall.

But the reality is that these operas, while dating to the 18th century, are in many ways more relevant thematically than operas that would come later. And in the hands of David McVicar, they come across as modern masterworks.

His Best Work

Let’s just get this out of the way – McVicar’s “Giulio Cesare” is probably the best production he has ever directed at the Met. Or at least it was, until “Agrippina” opened on Thursday, Feb. 6, 2020, giving Met audiences what is without any doubt, the intellectual pop hit of the 2019-20 season. This is a production with so much on its mind, but so full of pop culture references that it can truly hit a wide ranging audience in one go. It is a mad romp from start to finish with so much pizzazz that its three hours of music and endless sequence of arias (albeit with some sections cut from the original score) will fly by without you ever noticing. In McVicar’s hands, “Agrippina,” much like his “Giulio Cesare,” feels like the most relevant and powerful of all operas.

As you enter the theater, the first image plastered across the stage is of the mythical she-wolf and two little babies, Remus and Romulus. The reference indicates that Rome is thriving. When she reappears at the close of the first half, during Ottone’s famed “Voi che udite il mio lamento,” the curtain portrays the she-wolf as hurt, but still standing, mirroring Ottone’s own fall from grace and the state of affairs being painful and chaotic. A third appearance of the She-wolf takes place during Nerone’s “Quando invita la donna l’amante,” and here we see an image similar to the opening curtain, suggesting, in Nerone’s eyes, that all is well in the world. But the final curtain of the opera, after Nerone has been crowned the next Caesar shows the She-Wolf murdered, her body upside down to suggest that the image of Rome’s nurturer has been slain.

Those images hit even harder when you see it as a visual “State of the Union,” if you will, as it reflects on the narrative and its characterization of the main players. Ottone is the sole expression of honor and all that is good and true. And yet, he is constantly thrown around like some toy by the other characters; at the end of the first half, Handel presents three straight arias by Agrippina, Nerone, and Poppea in which they lambast the poor guy as a traitor, for doing absolutely nothing wrong.

Meanwhile, Pallante and Narciso, a general and politician respectively, are portrayed as polar opposites in their manners, but both prove to be fools that Agrippina uses and abuses without any remorse. In the case of Narciso, he is portrayed as bespectacled spineless coward who cries when the going gets tough, giving into Agrippina’s every suggestion because he’s afraid of what she might do to him (his physical qualities and characterization might remind Americans of a prominent political figure). Meanwhile the great General Pallante is like a dog that barks but never bites. He struts about with braggadocio, but then becomes putty at Agrippina’s mere smile.

Poppea is at the core of the story, serving as a moral anchor in many ways. The narrative turns as she turns. She’s an ingenue at the start of the opera who eventually realizes she is being used like a common tool for more powerful people. When she smarts up and starts to use the system to her advantage, she not only uncovers the lies surrounding her, but manages to get what she wants (a certain political party might learn a thing or two from her). But McVicar doesn’t let her off the hook all that easy as the final moments of the opera suggest that the lure of power might be too much for her. As Nerone ascends the throne, he throws her a look. Poppea walks over to the staircase and reaches out for him, only to be stopped by Ottone. It seems that even she cannot escape the lure of power, harkening back to the beginning of the opera where her very first lines were all about the attraction that jewels hold for her. Her wardrobe which shifts from a silky white dress to a black skirt with a light top to a grey sweater to, ultimately, a black dress, suggests her progression into the next “Agrippina;” in history, of course, Poppea would become Nero’s second wife.

Then there is the triumvirate of Claudio, Agrippina, and Nerone, who when seen as parts of a whole, might hit strikingly and uncomfortably close to home.

Claudio is a golf-playing, red-tie wearing fool who has a penchant for sexually harassing Poppea and, despite being the man in charge, never seems to have a clue as to what is going on around him.

Nerone is a snake-like teenage junkie and hypocrite who, at one point, goes around handing out meals to the poor while giving them the finger and toying with their emotions; he is doing this precisely to boast about how much he is doing for those very people and thus legitimizing his claim to the throne. He sexually harasses Agrippina while constantly feeling himself up, almost as if compensating for the masculinity he wishes was there but probably isn’t (it’s a pants role). He’s so inept and clueless that he even needs to be carted around by two security guards and when he ascends the throne at the opera’s end, you know that this government is going to implode.

And then there is Agrippina, dressed in black, a woman so concerned with maintaining power that she’ll lie and lie again to get what she wants. She hatches a quid pro quo with both Pallante and Narciso that involves giving them the chance to rule alongside her in exchange for helping push Nerone’s claim to the throne. When that plan fails and Ottone is named successor, she smears the hero’s name in the eyes of all the major characters. And when that plan also starts to get away from her, she promises the “hope” of sex and power for Pallante and Narciso in exchange for them murdering her political opponents. And despite being uncovered, she manages to talk her way into salvation, AND get what she wants. She is the traitor that turns everyone on themselves and still comes away without a single scratch.

(Credit: Marty Sohl / Metropolitan Opera)

Funny Business

McVicar manages to escape the feeling of a didactic play by framing it all as satire (again, it hits close to home). Besides allowing the characters to explode into their most exaggerated traits (Narciso being a crybaby, Nerone always acting like he’s high), McVicar is exceedingly clever in how he stages the text, giving it new and very appropriate context. It is not an exaggeration to state that the dialogue is so freshly directed that it feels rather current. At one point, Nerone dumps a can of cocaine on his table and then proceeds to sniff it in one fell swoop. His next line of dialogue kicks off with “Come nube che fugge dal vento (Like a cloud that flies from the wind).” That tiny detail was not lost on anyone in the audience, delivering what was probably the single-most enthused and prolonged laugh of an evening full of them.

Earlier in the opera, Poppea heads to a bar to drink away her troubles. After singing “Bella pur nel mio diletta (with one guy clumsily and creepily taking selfies with her from afar),” she notices her beloved Ottone arriving in the space. She takes a pot of flowers and hides herself behind it. Ottone arrives and sings “Vaghe fonti, che mormorando (nebulous springs)” as he pours him self a couple of shots. Then he notices Poppea “hiding in the flowers.” Poppea then attempts to hide herself face down on the bar, to which Ottone remarks that she looks beautiful as she sleeps. These recontextualizations of the dialogue are present everywhere in this production; many directors, when they can’t find a way to make the text work with their concept will either cut it or simply ignore it and hope that audiences won’t give it too much thought. The fact that McVicar has not only preserved much of it, but given it new meaning, speaks to his mastery.

McVicar also plays up the self-awareness of baroque opera. He doesn’t hide away from the fact that the music of this era, is at its core, dance music and he uses that to his advantage at every turn, whether it be Ottone having a boy band moment with two other fellow soldiers during “Coronato il crin d’alloro” or seeing two dancers go at one another during the big harpsichord duet in the middle of the second act. The other characters, particularly Agrippina and Nerone, also dance about in many of their own solo numbers to equally lively and comic effect.

He also isn’t afraid of poking fun at the recitatives’ self-referential manner. In the final act, he hides Ottone and Nerone away in closets on opposite ends of the stage. Whenever it is their respective turns to deliver a quick line while hiding, they poke out their heads out and deliver it; each of these interjections resulted in an excited laugh from the audience.

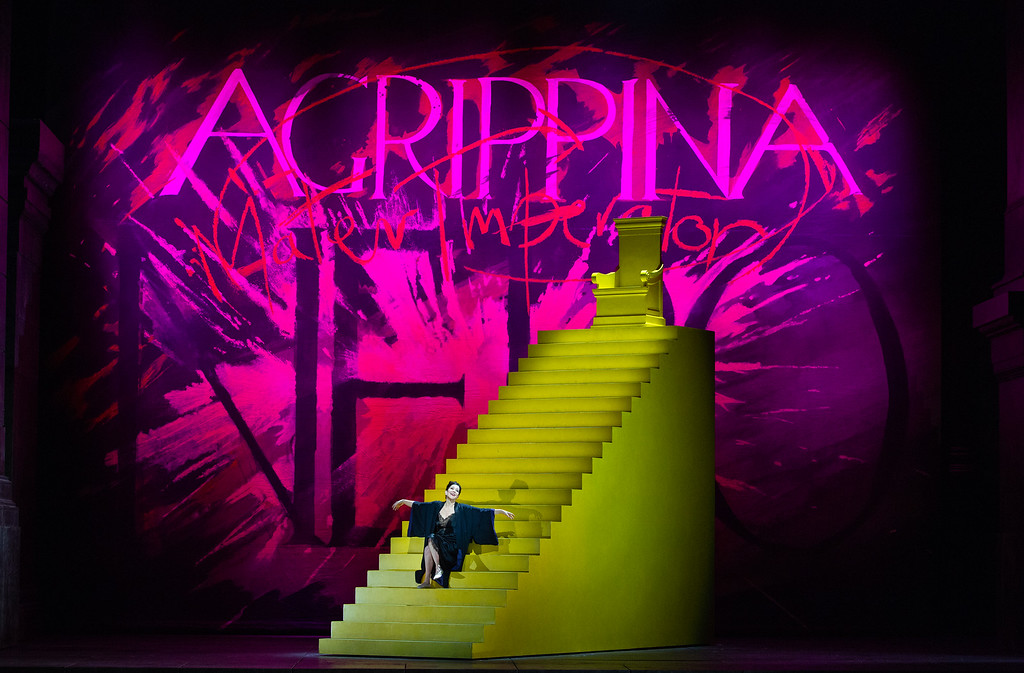

The sets are rather spare, but extremely well-incorporated. A golden staircase with a golden throne dominates the scenery, rotating about during the opening scenes. It’s the object of every single person’s desire and seems increasingly within reach for Agrippina in that early going. But as her plan implodes, so too does the staircase recede into the background, completely disappearing when Poppea takes over the narrative in the middle of the second act and for much of the third. Once Agrippina’s power grab becomes more fruitful, the golden staircase makes its prominent return, dominating the final scenes of the work.

In between, McVicar and company litter the stage with stone walls that bridge the gap between this modern setting and its history, almost suggesting to the audience the great link between the stories of the past and their reflection on the modern world; history in fact, does repeat itself because no one cares to learn from it.

McVicar furthers this theme by showcasing a news reporter trying to make sense of the mess going around with Claudio’s death and Nerone’s upcoming coronation. The reporter, followed by a camera crew doesn’t ask questions or even show any sense of agency, but simply points a microphone and camera at the characters, letting them dictate the narrative. Nerone is the main focus in the early going, but when Ottone’s heroics take over, the news reporter drops the initial story without any reflection and immediately jumps to the next big scoop, allowing Ottone to have the spotlight. We see his face on a tiny screen on stage left, the substance of the news less important than the fact that it is being reported. In this context, the news, as depicted, is more a mouthpiece for others to tell their version of the story rather than an entity holding them accountable or even showing any agency in the political process.

This is a truly mesmerizing production and the Met Opera should really consider giving McVicar a blank check to direct all the Handel operas his heart desires.

In the pit, Harry Bicket did a fine job of navigating a lengthy evening. The Met isn’t always the most suitable match for baroque music with its massive size requiring singers to really drive the sound to the farthest reaches. As such, the faster arias, with plush orchestration could sound a bit one-dimensional in their approach; conversely, more intimate arias, such as “Voi che udite il mio lamento,” and especially “Pensieri, voi mi tormentate,” tapped into greater stylistic color both in the orchestra and on stage. Nonetheless, Bicket’s choice of tempi was always quite spot-on; the faster arias moved quickly and gracefully, while the slower pieces had greater breadth and thus provided glorious musical contrast. At the harpsichord he was in fine form throughout.

A special shoutout must be made to Bradley Brookshire who played the harpsichord ripieno and even got a spellbinding solo in the second act alongside Brenda Rae’s Poppea. That particular aria featured a lot of coloratura runs for the soprano doubled by the harpsichord; if that isn’t difficult, then I don’t know what is. In any case, Brookshire proved exceedingly attentive to the soprano and after a bit of a discordancy in the first section of coloratura, he combined very well with Rae in ensuing sections.

(Credit: Marty Sohl / Metropolitan Opera)

The Power Behind the Throne

At the core of the opera are two women locked in a battle of wills. As staged by McVicar, they are also the most complex and intriguing of characters.

DiDonato’s Agrippina is a true villain, but in her hands, it is impossible not to feel compelled and even drawn to her. She seduced, manipulated, terrorized, belittled, flattered, and cajoled every character on stage in order to win and moved about the stage with agility and a fierce nature.

The mezzo displayed a complete sense of control not only with her sense of freedom about the stage, but also in her vocality, particularly whenever tasked to throw around an insane amount of rapid-fire coloratura. Nowhere was this more present than in “L’alma mia fra le tempeste.” If you have heard her recently released recording of the opera, you already know how fluid she is with the coloratura in this particular aria. But the tempo during the live performance seemed almost almost twice as fast with DiDonato taking even greater liberties during the Da Capo; her repetitions of “spera” seemed to offer her some space to prepare for the final flurry that eventually led to an extensive cadenza to cap off a true sign of virtuosity. If you wanted any proof that Agrippina was in charge, this was it.

Her sense of strength and control seemed at its most playful when she met Poppea for the first time, entering with the same exact dress as her rival and then matter-of-factly telling her that her boyfriend Ottone has betrayed her; most impressive was how straight and relaxed DiDonato played this moment, adding to this sense of control and purpose.

But it wasn’t meant to last and eventually things started to fall apart for her. In perhaps the dramatic highlight of the night, DiDonato entered slowly with a bottle in hand as the strings pounded out the opening notes of “Pensieri, voi mi tormenti.” On the initial D natural, she floated a pianissimo D natural on a straight tone, crescendoing it gloriously into the rest of the vocal line. She repeated this once again on the ensuing phrase, ushering in a sense of pain and grief. You could sense Agrippina losing her grips on the situation and the hushed tones of this delicate section suggested a defeated character. But then, she exploded with sound during “Ciel soccorri,” her singing impassioned and aggressive, the mezzo-soprano suddenly accenting consonants and adding a graininess to her sound. It didn’t necessarily empower her, but perhaps suggest an increased desperation. The Da Capo saw her expand the phrases of the slow section all the more, adding to the depth of pain that Agrippina was feeling. You wouldn’t be off the mark if you imagined this as a mad scene of sorts.

So when she followed that up with two violent scenes opposite Pallante and Narciso, you could really feel that Agrippina was at her limits. DiDonato did not hold anything back at all, even allowing Pallante to pull a gun on her and pushing it right into her mouth. In these moments, she actually regained her strength and was the dominant figure from the opera’s opening. As she did during “L”alma mia fra le tempeste,” DiDonato danced about, a smile on her face as she pushed scenery aside throughout “Ogni vento ch’al porto lo spinga.” Here her singing was playful; the elegant virtuoso at work yet again. Then she capped it all with the ultimate power play – a glorious rendition of “Se vuoi pace, o volto amato.” In this aria, Agrippina tells Claudio that peace would require him to set aside his hate. In the context of this performance, one can imagine she’s using him yet again to get what she needs – forgiveness for herself and her son. DiDonato sat beside the stupefied Claudio and delivered a gentle rendition of the aria. It was transcendent and came off as exceedingly sincere. DiDonato’s voice never rose above mezzo piano the entire time, drawing the listener in every step of the way.

And this was reminiscent of her entire performance; she didn’t just have the characters onstage tied to a string. She had the entire audience singing her tune.

(Credit: Marty Sohl / Metropolitan Opera)

Her Equal

Right there with DiDonato was Brenda Rae’s Poppea, in her Met Opera debut. Poppea is the motor of the plot. While Agrippina wants to dominate every man in the opera, almost every man in the opera wants to dominate Poppea. And as such, she kicks things off as a seemingly vapid and passive woman. Surrounded by her posse, the first words to come out of her mouth are “Vaghe perle,” an aria which Rae delivered with sweet and poised sound. It was beautiful singing and furthered this idea of her as a jewel. When Agrippina arrived on the scene with the same dress, Rae interpolated a high note to express her enthusiasm, furthering this sense of innocence.

A few moments later, she had to take off the dress and return to a less chic combination of a skirt and sweater, which was then removed for her big scene with Claudio. Clad with a sweater over black undergarments, she hit her lowest point in this scene as she ran away constantly from the incessant sex drive of the emperor (at intermission I was reminded that there is a pretty prominent court case taking place about some major motion picture mogul who had a striking resemblance to Claudio’s portrayal in this opening exchange).

It was here and in her ensuing aria “Se giunge un dì spetato” where she seemed to regain control of her narrative. In a musical move that mirrored Agrippina’s first aria, Rae spun an endless series of fiery coloratura, each one more intense than the last. It was a fair contrast to her laid-back entrance aria, announcing her as a central protagonist of the story.

She wouldn’t lose that handle in the ensuing scenes. While she sounded underpowered in the lower tessitura of “Tuo ben è il trono’s” opening lines, she fired away with forte sound on the second stanza that started on E natural. Then she really took control of the audience’s attention in the first scenes of the opera’s second half.

Struggling with her guilt over Ottone’s fate, Rae played Poppea in a drunk stupor, constantly losing grips on the situation and shuffling about to figure it out. As the scene progressed, she retained a sense of control, whether it be her coloratura duet with the harpsichord or her raunchy seduction of Nerone that mirrored Agrippina’s own handling of Narciso during his first and second arias. All the while, her singing blossomed, the soprano really coming into her own as not only a tremendously gifted singer, but a potent actress all the same. Of all the personages in the opera, her Poppea had the most visible and tangible character arc, providing the work with a strong moral center.

(Credit: Marty Sohl / Metropolitan Opera)

Clumsy Men

And while the women duke it out with complex and compelling characterizations, the men are made to look as mere pawns throughout the performance. And in the context of this production, they were mainly framed as archetypes taken to extremes, a band of bumbling idiots in many cases.

No one was more extreme in depiction than Kate Lindsey’s tattooed Nerone. Constantly high and wiping her nose, Lindsay’s Nerone was a snake. At one point early on in the first confrontation with Agrippina, Lindsay lay flat on the floor and pushed herself along in a visual callback to the slithering reptile; her head movements also mirrored those of said creature. Her hands constantly slid up and down her crotch area, a representation of the character’s obsession with his “potency” and self-pleasing nature. This was most evident during the aria “Quando invita la donna l’amante.” Lindsey sang a lot of the aria on the floor, her hands moving about her lower body. At one point she did a side plank and sang, drawing intense audience laughter, but showing the character’s misplaced narcissism. And if she wasn’t doing that, she was dancing around clumsily like some wannabe rock star of the 90s. Or she was giving everyone the middle finger. It was hilarious because it was ridiculous (ridiculously well-executed).

The ascension to the throne on two instances mirrored Nerone’s juvenile nature. Instead of taking the act seriously, Lindsey crawled up the stairs, like an animal ready to launch itself on its prey. In the final moment, her Nerone danced up the stage in some exaggerated Michael-Jackson imitation.

Then there was “Come nube che fugge dal vento,” a scene which Lindsey knocked out the park with increasingly manic physicality matched only by some rabid vocal feats of coloratura. Like Rae and DiDonato, Lindsey showcased a complete sense of command with the rapid vocal passages; she also seemed to have pulled off the highest interpolated note of the evening during a coloratura run in the Da Capo section. This scene alone drew the longest ovation of the night and had the audience in stitches.

Lindsey also made sure to not portray Nerone as any kind of lady’s man. In the first act, he seemed to have some Oedipal attachment to his mother, something DiDonato’s Agrippina was keen to encourage but deny all the same. And when it came to Poppea, Lindsey’s Nerone looked like a boy meeting a real woman for the first time and losing it. If Narciso tried to hide his excitement at playing with Agrippina, Lindsey’s Nerone was all too happy to get Rae’s Poppea to ramp up the fun. It was crude, but it definitely cast him in a very different light from his main rival Ottone.

What was stunning about Lindsey’s performance was how nuanced most of the singing was. While the opening “Con saggio tuo consiglio” was animalistic in its aggressive phrasing, “Qual piacer a un cor pietoso” was the polar opposite. Sung mainly with the thinnest thread of straight tones, she wove a sublime legato throughout the aria, all while mocking the poor people around her; again this mirrored DiDonato’s final interpretation of “Se vuoi pace” in its sublime hypocrisy. “Quando invita la donna l’amante” featured a mix of these two arias, moving from a fiery and accented phrasing of the text to a sensual straight tone on longer notes.

This was Lindsey’s first performance at the Met in five years. It’s good to have her back.

Bass Matthew Rose interpreted Claudio as a boorish oaf, a man who thinks that he can do as he pleases because he has power. But he would wind up being the punchline in most cases, his aggressive attempts at landing Poppea as pathetic as those of Nerone.

Handel’s music doesn’t allow the character much sense of depth either, his arias all about his sense of strength and how he will impose his will. Rose obliged them quite well, wielding imposing full tone in each of them, though his descents into the lower Ds on “Cade il mondo” were a bit lacking in strength. Still his dedication to giving Claudio vocal potency, only added to comic context around him. No matter how hard he tried to impose his will, he was the one who seemed least in control.

(Credit: Marty Sohl / Metropolitan Opera)

Prim & Proper

Countertenor Iestyn Davies played a rather square Ottone, perhaps providing the least personality in a cast full of them. That isn’t necessarily Davies’ fault at all. Ottone needs to be virtuous, prim, and proper in order for the other characters to really have their impact. Even when doing his boy band dance during “Coronato il crin d’alloro,” there was stiffness in his movements that gave him a naïve and boyish charm. In this aria, his singing sounded fluid and easy, Davies managing the quick moving lines with elegance; it encapsulated the hero at his most confident and collected.

Contrasting that was the final aria of the first half where Davies expanded the lines, giving a mournful quality to “Voi che udite il mio lamento.” The countertenor demonstrated exquisite blending of legato lines with his breaths, particularly on the two and a half measures tied together by “dolor;” this particular passage had an expansive quality that emphasized the sense of abject loneliness and pain. He also managed some stylistic nuance, delivering a few notes in a delicate straight tone that furthered this sense of vulnerability for the character. A similar melancholy took over his “Vaghe fonti,” also sung gently and with very polished legato line.

In the lone duet of the opera, he melded his voice gloriously with that of Rae, the two truly connecting as one musically.

As Pallante, Duncan Rock played up the role of the self-confident general in his initial appearance before Agrippina. His vibrant sound throughout “La mia sorte fortunate” doubled this sense of strength, even though his triplet runs on “fortunata” were muddled. “Col raggio placido della Speranza,” despite putting Pallante in a more discomforting situation dramatically, was delivered with more vocal precision, giving the character confidence in a moment where he seems to be losing it.

His polar opposite was Nicholas Tamagna as the spineless politician Narciso. The countertenor showed a more timid disposition in his initial meeting with Agrippina, which made him more malleable for her. His aria “Volo pronto e lieto” was one of the comic high points of the night. Seated next to Agrippina, he sang the first section of his aria sweetly and gently, almost as if romancing her. But halfway through, right before the Da Capo, she put her hand between his legs. The countertenor’s musical variations were thus sexually charged utterances that produced a great sequence of laughter throughout the auditorium. At the close of the aria, he took a newspaper and covered himself up, the imagined graphic image adding to the hilarity. It seems that that moment scared the man in some way, as his subsequent meetings with the overpowering Poppea were met with tears and hysteria. His second aria, “Spererò, poichè mel dice” was less a consolidation of his loyalty to Agrippina and more of a plea for release from emotional bondage.

These two characters are probably the most uniquely realized in this production. Taken at their word as originally written by librettist Grimani, one can imagine many versions of this opera in which the two men are merely representations of the same idea – corrupt men ready to do anything for a woman they want to possess. They might even be completely indiscernible outside of their ranks and positions and the musical characterization. But having them play as foils to one another, adds to the comedy of the production and also its ability to illuminate. In their final notable act in the opera, the two walk onstage tied together as they point a gun and syringe at one another; corrupt military and politicians will always be tied together.

As Lesbo, Christian Zaremba played the role of assistant to Claudio, always seemingly arriving at the worst possible moment with the worst possible news for the characters he is announcing it to. He breaks up Nerone’s coronation party (singing the sprightly but intentionally irritating “Allegrezza! Claudio giunge” with a warm and potent sound) and then interrupts Poppea constantly to annoy her about Claudio; when Claudio is locked in a battle of wills with Agrippina, Lesbo interrupts to tell him that Poppea is waiting for the emperor. When he is doing his best to seduce Poppea, Lesbo tells him that Agrippina is on her way.

This was just the opening night and it was clear that this production was intensely rehearsed and conceived by all of the participants. There is tremendous passion and attention to detail onstage (of which I didn’t even describe a sizable percentage) and is equally compelling for anyone witnessing it unfold. And the best news? It will probably only get better through the ensuing performances, which means that anyone heading to New York in the next month should be getting their tickets right now.