Metropolitan Opera 2017-18 Review – Tosca: Yoncheva, Grigolo, Villaume Not Ready for Primetime

By David SalazarThis review is for the performance on Jan. 4, 2018.

It was the most hotly anticipated production of the new Met season, the run-up to its unveiling on New Year’s Eve as big a melodrama as the opera itself, filled with unexpected twists and turns.

And like the opera itself, where its final act feels like an anti-climax after the masterpiece that is Act two, the production itself proved unable to live up to the hype that its pre-production hinted at.

In the last year since the announcement of this production, we have seen three cast changes and two conductor changes. No doubt that would impact the ultimate outcome as two of the main pieces to the puzzle would be taking on the opera for the first time in their entire lives.

Back to the Future…

This David McVicar production is nearly a decade in the making, with Luc Bondy’s combination of an erratic vision and Ikea furniture getting jeered and booed unexpectedly on its opening night performance. It replaced a production by Franco Zeffirelli that while panned by critics for its sheer size, was undoubtedly glorious in its hyperrealism. No doubt general manager Peter Gelb knew that financially, the disliked Bondy would need to be replaced by something more akin to the Zeffirelli as to bring in more audiences and revivals of the undisputed warhorse.

So it was no surprise that Gelb would turn to David McVicar, whose productions at the Met at there best are insightful and revelatory (“Il Trovatore”) and at “worst,” conservative and serviceable. “Tosca” doesn’t quite fit into either.

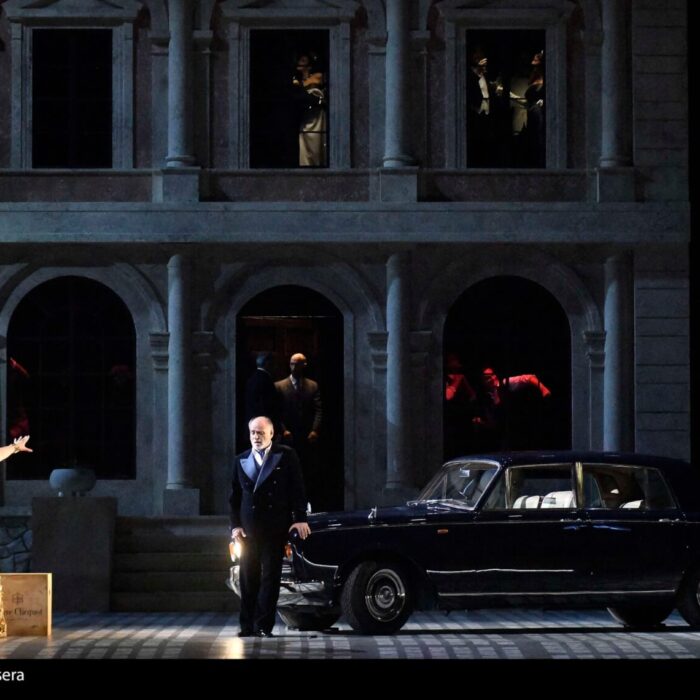

It almost completely recreates the grandeur of the Zeffirelli first act with the imposing church filled with lush details and architecture exactness. Act two is an elegant antechamber at the Palazzo Farnese filled with all the items one might expect – Scarpia’s desk, a sofa, a door leading to the torture chamber, a table with food, a knife, the candles, and crucifix. Act three is the most minimal of the three, taking place atop the Castel Sant’Angelo at night. If you crave a reminder of what Zeffirelli brought to the opera, then this will certainly fill that appetite.

…But in what Direction?

If what you seek is a new “Tosca” that gives us brand new insight into the great themes of Puccini’s opera – the relationships with authority, the different characters’ relationships with God and religion, the importance of self-determination or lack thereof, sexual abuse – they aren’t really there at all. In all frankness, given the way the production is set up, McVicar didn’t really leave behind an indelible touch the way he does in his “Trovatore” or “Giulio Cesare.”

His blocking tends to be rather free, random, and at worst, ill-conceived, with Tosca and Scarpia’s confrontation in Act one distracted by the arrival of guests into the church in anticipation of the “Te Deum.” The viewer simply doesn’t know where to look, so prominent are the background actors. Intellectually we know where we need to look, but the curiosity of seeing new costumes and designs, some more intricate and unique than the white dress Tosca wears or Scarpia’s dark uniform, draws our attention.

The same held true for the final act wherein Tosca reconvenes with her lover before his, unbeknownst to her, death. The two are kneeling on the floor stage right. Intellectually the viewer knows that that is the most crucial moment dramatically, except that something far more interesting and unexpected is happening upstage. The soldiers who had been keeping watch of Mario are suddenly being told to rush off stage rather hastily. The hubbub that this causes undeniably distracts the viewer, garnering more attention for its unexpected nature. It also doesn’t help that the soldiers are wearing rather bright blue colors that stand out amidst the darker hue of the other costumes and set overall. Guess where this writer’s attention turned?

The confrontation between Scarpia and Tosca in the second act is one of opera’s most tense moments, and with the explicit sexual assault at play, it should be one of the most unnerving as well. But the direction is “polite,” the performers often kept at a distance, Scarpia’s own monstrous behavior kept in check throughout the performance. When the libretto imposes the violent actions they seem forced and awkward at best. For example, there is one moment where Tosca vehemently repulses Scarpia, telling him “Non toccarmi demonio (Don’t touch me demon!).” However, Sonya Yoncheva was all the way stage left and Zeljko Lucic was on the complete opposite end of the stage. They moved toward one another without any motivation just to ensure that that one line made sense. Lucic barely ever touched Yoncheva in this scene and his glances themselves never revealed any lust whatsoever. Maybe current social contexts forced a restrained direction here, but it surely didn’t create much tension emotionally.

The murder itself was also strangely staged. When Tosca turned her attention toward the knife, it was impossible to discern that she was, in fact, looking at the knife as one could easily confuse her glance as one toward Scarpia. To that point the knife itself wasn’t in focus at all, so its sudden appearance when she retrieved it was anti-climactic, the buildup undercut by the choice of staging the two objects of her attention, the knife and Scarpia, in the same direction.

But the actual murder worked less. After stabbing Scarpia once, McVicar directed Yoncheva to walk all the way around the circular table to stab him yet again. Initially, this writer thought she was walking away from the wounded tyrant to look for an escape route. It made sense. Tosca had just stabbed a guy and she would probably be so shocked that she might see it as a chance to escape. But instead, she just looped around the table rather casually and stabbed him again. Why not just stab him in the back? Or walk up behind him, turn him around and stab him again? The roulettes around the table didn’t look good in the theater and Yoncheva herself seemed like she was marking the movement to follow a direction instead of a character motivation (more on that later).

Other questionable choices include turning the Sacristano into some sort of a cartoon character (Cavaradossi throws his coat on him as if he were a coat hanger for some reason), Tosca’s white shawl that gets thrown around the floor of the church repeatedly for no concrete reason, and the choice of having Tosca walk up to the ledge and prepare to jump well before she is in any real danger. It didn’t come off as an act of desperation but simply a requirement of the libretto.

On the plus side, this production leaves itself wide open to performers who “direct themselves,” as will be the case later this season when Anna Netrebko takes on the major diva. She no doubt could potentially tap into new possibilities that McVicar and his current cast overlooked.

Vocally Tosca… But Not Fully

When the director has no concrete or unique perspective on the characters or drama, it falls heavily on the actors themselves to bring it to life, a feat made more difficult when those in charge are doing it for the first time, namely Sonya Yoncheva, Vittorio Grigolo, and conductor Emmanuel Villaume.

Yoncheva has a glorious instrument. It’s massive, rich in texture, and highly expressive. She’s an incredible vocal artist, her finest moments coming in the first act, particularly in expressing her love for Mario in “Certa son del perdono,” her ascension into her upper vocal stratosphere truly divine. She had the coquettish nature down vocally, brightening and lightening her sound to tool with Mario in church. She also delivered a heart-wrenching “Ed io venivo a lui tutta dogliosa,” her phrasing delicate and frail as she whimpered of her lover’s betrayal. “Vissi d’arte” was unique in its approach, the soprano holding back volume to create a prayer-like atmosphere. It made the aria more introspective and intimate. In some ways, it was the vocal performance one could wish for from any Tosca, especially one singing it for the very first time. She certainly borrowed from other great Toscas of the past (her repeated “Mori” crescendoed each time in a manner reminiscent of Hildegard Behrens’ visceral interpretation, and her final lines were a callback to Maria Callas’ incredible portrayal) but her singing ultimately left one engaged.

But while Yoncheva is a great vocal artist, she is not a complete one. Acting has never been her forte and on evidence of this performance, she still has a long way to go. She goes through the motions rather passionlessly, often looking rather robotic in her gestures. The aforementioned stabbing scene didn’t work because she didn’t sell the sense of anger or desperation. Her walk around the table before the second jab was leisurely in its execution. And once she had stabbed the man, she didn’t seem to have much of a reaction to her crime. Here was a pious woman who didn’t want to kiss her boyfriend in front of a statue of the Virgin Mary, and she had just killed a man. Yoncheva didn’t seem shocked or traumatized in the least. The soprano did the usual movements – washed her hands, fumbled a bit around the desk looking for the passport, grabbed them from Scarpia and then put down a few candles and a crucifix on him before walking out. It was all delivered as if she were on autopilot, the soprano not taking many moments to reflect on any of the actions. Not once was there any indication of fear, whether it be in her movements toward the corpse or otherwise. The placement of the candles and crucifix was done without Tosca taking a single moment to even consider it.

Other moments didn’t help her acting either, especially the one where Tosca asks Mario if she can reveal the whereabouts of Angelotti. It’s supposed to be a conversation between the two in hushed manner, Cavaradossi in another room altogether. Tosca says “Mario, consenti ch’io parli?” and he responds “No! No!” Yoncheva was downstage, far from the door where Mario was, which was located upstage. How could they possibly hear each other from such a massive distance? Opera requires suspension of disbelief, but in a production that is supposed to pride itself on realism, this didn’t quite fit. The reason this happened might have been another McVicar mistake, or it could have come down to the fact that Yoncheva could not stop moving about the stage throughout the entire second act. On one level, one might interpret the incessant wandering as a woman looking for a way out of her predicament. But Yoncheva was ultimately more effective at portraying this trapped state the moment she stopped moving. She looked cornered in those instances and one must wonder why McVicar felt it more appropriate to allow her to move about so aimlessly.

This is her first Tosca and that must be taken into account. Vocally she’s there, but there is, to this writer’s eyes, still ways to go for her.

Vanilla

As Scarpia, Zeljko Lucic came on at last second when Sir Bryn Terfel withdrew from the production on Dec. 12, 2017. Of all the artists in the cast, he was the most seasoned in his role, but it didn’t show. Lucic has an elegant baritonal quality, smooth legato, and firm resonance. But one could not call his interpretation complex, visceral, or even varied for that manner. From his first “Un tal baccano in Chiesa” onward, he sang with the same style of phrasing, sound, and color. There were some variations here and there, but his Scarpia lacked aggression and violence. It was all very properly sung, undercutting the sense that this was a masterful and villainous manipulator. Harsh accents or any kind of vocal flavor were largely absent from the performance creating a rather vanilla portrayal, which has become Lucic’s signature (with the exception of his excellent Macbeth). His upper notes tend to go flat in pitch, no doubt hindering his performance and his voice was rather small in the “Te Deum,” even though the orchestra seemed to be far quieter than usual to help him out. One could barely hear him as he belted out “Tosca, mi fai dimenticare Iddio!”

There was one moment that I absolutely loved from Lucic, everything else withstanding. It came in the middle of the “Te Deum,” a portamento to the D flat on “Ah! di quegliocchi,” sublime phrasing you don’t get often in this passage.

No Lows or Highs

And yet, the most disappointing vocal performance of the evening fell to tenor Vittorio Grigolo. The tenor was also making his debut as Cavaradossi, though he knew far before any of the other castmates that he was to take on the assignment. Grigolo has a gloriously rich Italianate timbre that suits the French repertoire and much of the lyric Italian roles. His rhapsodic way with phrasing is legendary and among the many aspects that make him an engaging artist.

But his Cavaradossi was not quite among his masterpieces and to this writer’s ears, he simply could not handle the weight demanded for the vocal line. Let’s start with the lower notes. “Del sofferto martir,” which follows the two epic proclamations of “Vittoria! Vittoria” was not only inaudible, but the sound was gargled, forcing Grigolo to shout out a few words to bring some clarity to the text. Ditto for the opening lines of “E lucevan le stelle,” where Puccini essentially puts the entire opening of the aria in the tenor’s lower register. Again Grigolo’s lower reaches muddled, the voice losing focus and quality. He again compensated by accenting words in spoken manner, taking away from the shape of the phrase and line.

But the tenor’s challenge with the role was also in how he approached the middle and upper ranges. Grigolo tended to go full blast to compensate for an overall lack of polished legato. For him bigger was better, though it undercut any sense of richness in Puccini’s music. There was no build because Grigolo was already operating at full tilt vocally. This was the case throughout the entire “Recondita Armonia” and throughout “E lucevan le stelle” where he just pushed his instrument to its brink, the pitch wobbling out of tune. The wobble was also the main protagonist of his two “Vittoria!” cries.

Unsurprisingly the tenor’s finest vocal moments came in quieter passages, “O dolci mani” being an absolute musical highlight from anyone in the entire cast. Here we heard Grigolo at his best – the sound suave, the colors rich, and the legato refined. He also sounded most comfortable with Yoncheva in their duets, the two in sync vocally rather well.

Grigolo’s Cavaradossi came off as more of a hothead though it certainly worked well for the second act showdown with Scarpia. He was also successful at keeping Yoncheva’s constant wandering in check, holding her tight for them to sing together and look like true lovers.

Two Different Places

And now we move on to conductor Emmanuel Villaume.

Villaume was a revelation in “Thaïs” just a few months back in one of the finest conducting displays of recent history. Ditto for his “Roméo et Juliette” last season. But Puccini is not his thing, at least not yet.

One might congratulate him on managing to coalesce the wild orchestral forces into something squeaky clean, so polished were his colors overall. But his overall polish and sense of musical architecture makes the entire enterprise lack in vibrancy. “Tosca” is an opera replete with urgency and extremes. Just look at the final moments of Act two, the repeated chords in low, somber tones suddenly erupting with frenetic percussion. It’s meant to shock us out of the calm that has dominated the music for the last several minutes. But in Villaume’s hands, we barely feel that subito fortissimo. It’s almost non-existent. And so the act ends without the chill of impending doom.

The tempi themselves are overly slow, the entire coda of the second act, from when Tosca contemplates the murder, executes it, and then leaves Scarpia with candles and a crucifix, languid in its pacing. It’s funereal but dispassionate. The sense of trauma is nowhere to be heard. It’s clean, but it doesn’t weep.

Villaume and his singers also seemed to be on different planes, most prominently Grigolo who has the tendency to conduct himself as far as rhythms go. He’s full of energy and uses it as he sees fit in the moment, but it obviously calls for a conductor ready to move with him. Villaume isn’t there just yet in this music. “Qual occhio al mondo” was one such instance where Grigolo seemed to want to push forward, but Villaume simply wouldn’t give. At one point, the tenor, who was wooing Tosca, turned from her and looked directly at the conductor with a bit of a frustration on his visage. “E lucevan le stelle” was a tug-of-war between the two, the orchestra not quite lining up with the tenor, often falling behind or pulling too far ahead. The same happened throughout “Vissi d’arte” where Villaume seemed intent on pushing ahead of Yoncheva, though to minimal detriment. Things did almost seem to get off the rails at the start of Scarpia’s first Act two aria “Ha più forte sapore,” the conductor blazing ahead of Lucic in the opening phrase. Lucic and Villaume realigned a phrase later, but it was clear that they weren’t quite sure on the right tempo for the section.

It was all rather surprising considering the genius that Villaume showcased in “Thaïs,” but again, one must wonder if this was the result of being called in last minute, on Dec. 5, 2017 to be exact, to take over an opera he has rarely conducted with two singers that had never performed it.

This ultimately means that this performance deserves one massive asterisk that states – “None of the people in this cast were originally intended to take on the roles they ultimately undertook. Some of them even undertook this task with just weeks of preparation.”

But that is not what we go to Metropolitan Opera for.