Los Angeles Opera 2018-19 Review: Hansel & Gretel

A Delightful Production At The Lighter End Of The Spectrum

By Gordon WilliamsThere are cases for quite serious readings of Engelbert Humperdinck’s 1893 opera “Hansel and Gretel,” which Los Angeles Opera has just opened at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in a revival of Doug Fitch’s 2006 production. In his program booklet essay “Hansel and Gretel” (“Fact and Fiction”) Basil De Pinto pointed out the opera’s very real concerns with hunger and poverty which, we soon saw, are established in the opening scenes where rumbling stomachs nevertheless cannot hinder two children, charged with an impoverished family’s chores, from fooling around and being kids.

In a blog note from the Music Director (“[It’s] not a children’s opera!”), conductor James Conlon made a case for regarding “Hansel and Gretel” as “Wagner’s shortest opera,” yet definitely one you could still bring your children to.

Wagner’s Shortest Opera

Of course, Humperdinck (not to be confused with Arnold Dorsey, the British pop singer, who took Humperdinck as a stage name in the 1960s) was Wagner’s assistant at Bayreuth and music histories rightly credit Humperdinck with finding a way out of what – for want of better words – could be called the “Wagnerian impasse,” the late 19th-century question of how to top Richard Wagner’s stupendous epics, such as the “Ring” cycle.

Humperdinck’s answer was spectacularly simple: revert to fairytales and folk-tunes (albeit orchestrated in a Wagnerian way). Doug Fitch’s production honored this lighter approach. In fact, the question of how light or dark to make “Hansel and Gretel” is one by which to evaluate any production. If Fitch’s production was more toward the lighter end of the spectrum – Susan Graham the witch in the forest who will eventually detain and attempt to cook Hansel and Gretel was clothed more like a tempting candy than an old crone – that too is an appropriate reading.

Humperdinck’s opera is arguably the lightest Wagnerian opera (if we want to continue Conlon’s analogies), a model of the simplicity which can conceal great depth.

Thoroughly Enjoyable

I thoroughly enjoyed this production and completely understood the bubbling excitement shown by director/designer Doug Fitch, librettist Richard Sparks, and movement director Austin Spangler when they ran out onstage at the end to take bows. This production testified to their successful collaboration.

Doug Fitch’s designs (he was scenery and costume designer, too) were immediately appealing. We entered the theater to see a jigsaw rendering of Hansel and Gretel’s family’s cottage in the woods. It was delightful to witness animated smoke coming out of the chimney on cue from the orchestra, and I was frankly moved as the activity in the orchestra pit intensified during the overture and the jigsaw broke apart (like a cookie?) to begin the tale. The sets created intriguing shifts of perspective, such as woodland mushrooms that towered over Hansel and Gretel when they were lost in the woods and flats that moved forward as scenes rolled by in the background. There really was a lot to see.

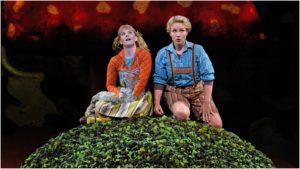

And there was a lot of attention to detail. Liv Redpath (Gretel) and Sasha Cooke (making her LA Opera debut as Hansel) were convincing kids, whether clowning around or bouncing off tummy-pillows that represented well-fed stomachs or trying to squirm out of adult furniture that had a life of its own. Theirs was a touching partnership, expressed so often in all those duets of tuneful thirds for which a lovely visual analogue was found in holding hands during the barcarolle-like number in which they first see the Witch’s house of sweets. “Hansel and Gretel” is also, very late in Act Three, a coming-of-age story, particularly for Gretel whose wonderment at all the children emerging from the Witch’s spell at the end was tenderly expressed by Liv Redpath in her line, “Their eyes are closed, they can’t see a thing. They’re sleeping and yet how sweet they sing.”

But it was lovely to see such good use made of the stage as was made by this production, and it’s no wonder that the creative team included a “movement director” in Austin Spangler.

Yet again, this was a Los Angeles Opera production where crowd movement was most convincing. The throng of children (Los Angeles Children’s Chorus) freed from their fates as gingerbread cookies at the end after Hansel and Gretel have shoved the witch into her oven moved with the sort of ensemble surge and flecks of individuality you see in a real crowd. Is great stage movement a hallmark of a Los Angeles Opera production?

A New Voice

But I mentioned librettist Richard Sparks. What do I mean? Wasn’t the libretto written by the composer’s sister, Adelheid Wette who died in 1916. Yes and Sparks’ English-language libretto clearly uses Wette’s German original as a starting point and paradigm, always rhyming and therefore – synchronized with musical phrasing – always making an impression; sometimes keeping quite close to Wette’s meaning; other times departing from it. Occasionally this meant emphasizing food rather more than Wette did. Hansel and Gretel’s famous dance-song became a Rice Cream Dance, with lines like: “With my tongue, I’ll lick, lick, lick” where you might other times hear, “With my feet, I’ll tap, tap, tap.”

Sparks and Fitch also downplayed the original’s religious overtones. The pantomime did not reveal fourteen angels emerging from the world of dreams to protect the children lost in their frightening forest but guardian forest spirits with luminous eyes ringing the children in a circle of safety. If not quite the dazzling vision of heaven that Humperdinck’s music appears to intend, the pantheistic theme was quite appropriate. After all, the forest (“der Wald”) is a German Romantic theme.

This production was always great to look at. Occasionally I felt that the sound wasn’t “forward” enough, however. At least once I felt that that imbalance was due to prioritizing of visual effect. Melody Moore as Gertrude (the Mother) first appeared onscreen. Her giant eye at the cottage window looking in on her errant children earned laughs, as obviously intended, and she managed one of the best double-takes I’ve seen when she saw her children inside the house clowning around instead of doing their chores. But I was relieved when an appropriate moment in the score justified her stage entrance. Her scene with Craig Colclough (as Peter, The Father) when she discusses the broken milk pitcher and how she has sent the children out into the forest to find the evening’s meal, was really a very impressive two-hander, with Moore vocally conveying a range of emotion, including sarcasm and other subtext.

As Father, Colclough really grounded the production. In his opening “Beer Song” his rolled r’s beautifully conveyed a drunken or supposedly drunken state, enough to upset Mother before he reveals that after all he has had a good day selling brooms (his craft) and buying food. His healing authority at the end of the opera, when reunited with his children was made the more convincing by what I would describe as the quality of firm spine in his voice.

And there was real horror in his realization that Mother has sent the children out into the forest where, so the townspeople have told him, there now lives a witch.

Star Of the Show

The star of this production was mezzo-soprano, Susan Graham. As the Witch, she did not appear until Act three. But it was worth the wait. Perhaps the Witch does not provide the opportunity for really beautiful singing as other roles in Graham’s repertoire but the mezzo was able to convey the deceptive appeal this lollipop-colored character might offer two hungry children in tones that were at times cajoling, at others even threatening and coarse.

Her performance might be called a great “comic turn” and there was an infectious relish in her characterization that earned for her Dance (in the original German: “Hurr, hop, hop, hop!”) one of the night’s two action-halting breakouts of applause.

Right from the start, the orchestra under James Conlon provided sympathetic and uplifting accompaniment. The gentle magic of the opening quartet of horns was as much the magic formula of “Once Upon a Time” as the jigsaw-like depiction of the cottage in the woods that greeted us on arrival. The beginning of the Witch’s Ride, almost before Father finished his words “Pray God that we find them before the witch” really catapulted us into Act Two. Everything was well-judged.

As the Sandman, Taylor Raven’s sedate appearance really calmed things down when Hansel and Gretel were on the verge of panic in the forest gloom, while Sarah Vautour charmingly brought everything back to life at break of day as the Dew Fairy. Incidentally, her costume with her standing on top of a tall cone, actually tricked me into thinking she was half her normal size.

So, what about “Hansel and Gretel’s” undertones? As an Australian, I occasionally think of the story of Humperdinck’s application to teach in Sydney when he was 60, and of his rejection. It was 1914, probably not a good time for a German to seek work in the British empire.

When I listen to “Hansel and Gretel” I often have this sad story in the back of my mind. But I couldn’t let it darken my enjoyment of this production. Nor should I have. The young folk in our row were sitting forward in their seats most of the night – and quite often, so was I.