La Fenice 2017 Review – L’Occasione fa il Ladro: Solid Ensemble & One Major Standout Lead Strong Presentation of Rossini Comedy

By Alan NeilsonWritten in only 11 days, “L’occasione fa il ladro” was the fourth of five operas Rossini had been contracted to write for Venice’s Teatro San Moisè. Although only a relatively small theater, with a limited budget and basic scenery and boasting only a small cast of singers and without a chorus, it was the perfect size for the one act farce which Rossini was to write for the theatre. At the time the Teatro San Moisé was one of the most important theatres in Venice, having played host to the premieres of many well-known works. Unfortunately, six years after the premiere of “L’ocassione fa il ladro” it was forced to shut its doors, a victim of Venice’s economic and cultural decline following the Napoleonic invasion. Following a brief period as a puppet theatre and then as Venice’s first cinema, it was finally converted into an apartment block in the early 20th century. Nevertheless, it was during this period that Rossini was to develop many of the structural and stylistic characteristics that so clearly identify his music today.

The libretto of “L’occasione fa il ladro,” written by Prividali, after a play by Scribe, is witty and elegant although largely unexceptional, and fairly typical of the genre. Two strangers, Don Parmenione and Count Alberto, meet at an inn, near to the city of Naples and, on leaving, accidentally take each other’s luggage. This simple error precipitates the normal confusion in which the two men then pursue the same woman, Berenice, who is disguised as her maid, Ernestina. Add in Martino, Don Parmenione’s servant, and Don Eusebio, Berenice’s uncle and the opera takes the normal course of a farsa (basically a compressed opera buffa), with its usual comedic misunderstandings, that are eventually resolved in a happy finale, along with the simple moral message: “If by chance a man has the opportunity to become a thief, sometimes there is a reason that makes it legitimate.”

Querini Sets the Scene

As the audience entered the dimly lit auditorium they were presented with a quotation by Querini, “Things written in books, and therefore eternal, are a theft perpetrated upon the laws of time,” written across the stage. This acted as the starting point for the director, Elisabetta Brusa. Rossini had the opportunity, through his genius, to undertake such a theft, by creating this work, which in its turn justifies the theft. Thus this production folds in upon itself in a very clever and amusing fashion.

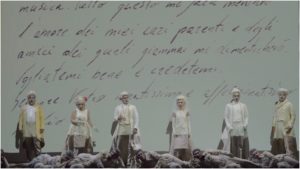

Brusa starts her production by having a letter, written by Rossini, projected onto the stage during the opening sinfonia, in which he talks about the creation of the opera, and finishes the evening with an another projection, this time of Rossini signing the letter – his work (theft) complete. In this, she was assisted by members of the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia, who designed the costumes, scenery, and lighting. During the course of the evening, we observe the creation of the work that will defy time and enter the eternal library. Before the commencement of the performance slow moving, white costumed figures, onstage and dotted around the theatre, observed the audience as they took their seats. Throughout the evening they helped shape and organise events, intervened to aid the singers, acted as servants and were equally surprised and delighted by the comedy; the timeless participants and observers to a work of art.

Although only a one act farsa, it is divided into two scenes, each with its own distinctive set, both framed by the page of a book, along with a written description above. The first scene was set in an inn, with a fireplace and a table and chairs; the second scene in a drawing room opening onto a garden at the rear. Everything was colored white, except for pastel blue walls in the second scene. The costumes, also in white, were not time specific. Imaginative hairstyles, again in white, helped to define the characters: long plaited hair for the women, thick peasant hair for Martino, a neutral short hairstyle for Don Eusebio, and conical shaped, backward flowing hair for the male lovers. The characters were played as types, with little depth. Set pieces were nicely constructed, without unnecessary interference from the director, and pleasing on the eye, but without too much movement. All of which may sound a little bland. Yet, in fact, it was quite the opposite. The scenes were delicate, balanced and refined – adjectives which could, in fact, be used to describe the entire performance.

The idea, however, to have the performance take place behind a transparent screen did not work. Whilst it may have added to the timeless quality of the production and help produce scenic pictures that looked like old photographs, it also distanced itself from the audience and had a blurring effect. This was further highlighted when the cast moved in front of the screen for the final part of the finale “D’un si placido contento,” in which the clarity and its immediacy were pleasingly enhanced.

Strong Ensemble

The cast of “L’occasione fa il ladro” all put in strong performances. As a group they interacted and blended superbly well, capturing the beauty of the music and the dramatic dynamism of the work. The quick-fire exchanges in the recitative sections were clearly delivered with subtlety, strength and verve, but it was in the ensembles that this was most in evidence, not least because the opera contains some very pleasing duets and a marvellous quintet at the opera’s midpoint. In particular, the duet “Se non m’inganna il core,” for Berenice and Alberto was a real gem. Both singers sang with exquisite elegance, ornamenting their vocal lines with delicate beauty, and were answered in turn by equally delicate phrases from the string and woodwind sections. What was clear from their combined performances was the extent of which this opera really is an ensemble piece; one poor performance would have destroyed the illusion completely.

The Standout

Nevertheless, one role did stand out, namely, Berenice, if only because Rossini supplied her with what is possibly the only truly great aria in the score, “Voi la sposa pretendete,” and one that defines her role. Berenice, played by Rocio Pérez, is the woman at the center of Count Alberto and Don Parmenione’s attention. The aria is in three-parts: in the first part, “Voi la sposa pretendete,” Berenice confronts the two men and demands the truth. Here Pérez sang with a great deal of dignity, delicately ornamenting the vocal line, if singing a little within herself. In the second part, “Deh non tradi…,” when Berenice offers her hand in marriage to Alberto, Pérez displayed a deep sensitivity, underpinned by beautiful phrasing and a fine legato. In the third part, “Io non soffro…,” Bernice finally loses her composure, angered by the ridiculous goings-on, and Pérez magnificently displayed her wonderful coloratura and vocal agility to demonstrate Berenice’s feelings, capping it with a wonderfully sustained rising vocal climax. Pleasing as her performance was, there was an unsatisfying element, in that Berenice is not a big role, and one was left wanting to hear more!

Consistency All Around

Possibly the most consistent performance of the evening came from Omar Montanari as Don Parmenione. He has a strong stage presence and acted his part well, moving easily between light comedy, superficial sentiment and self-indulgent anger. Moreover, he possesses a fresh, flexible baritone which he used with great élan, characterizing the vocal line with a great deal of subtlety and beauty. His diction is clear and he displayed excellent dynamic control. The part seemed to suit his temperament and voice perfectly.

Giorgio Misseri as Count Alberto also had a strong stage presence and made a suitable and worthwhile rival to Montanari’s Don Parmenione. However, whereas in the ensemble pieces his singing was strong, displaying a beautiful warm and clear tone, and his recitatives were delivered well, he will not have been too pleased with his execution of the aria, “D’ogni più sacro impegno,” in which he lost focus towards its end, and displayed a tendency to push his voice a little too much and thus compromised the sound.

As Don Parmenione’s wily servant, Martino, was the baritone Armando Gabba. He possessed a less refined sound than Montanari and was thus perfectly suited to his role as the servant. His quick-fire exchanges, primarily with his master, were fluid and well-delivered. Likewise, he delivered his aria, “Il mio pardoned è un’uomo,” well, if somewhat blandly.

Berenice’s sometime maid or companion, Ernestina, was played by Rosa Bove. Always playing second fiddle to Pérez’s Berenice, Bove put in a wonderful performance. Her voice was solid and strong across the range and her acting convincing. Enrico Iviglia was comfortable in the smaller role of Don Eusebio and produced a polished performance.

Under the baton of Michele Gamba, the Orchestra del Teatro La Fenice produced a sympathetic performance. Their playing was delicate and refined throughout and sparkled during the racier moments of the score. Gamba maintained a measured balance between stage and pit, giving singers the necessary space, whilst ensuring the orchestral dynamics were always under control.

Musically “L’occasione fa il ladro” is certainly not to the same standards of Rossini’s later buffa operas, and does not possess the drive and brilliant comedy that characterizes these works, yet on its own terms, it is a delightful opera. Although it will never have you laughing out loud, it is witty and charming, and if not overplayed will certainly amuse. If approached in the right frame of mind it is possible to sit back and enjoy a light piece of theater that entertains and delights, and in this sense La Fenice’s production can be categorized as a definite success, and although it will never become part of the standard repertoire this production proves it is certainly worth an occasional outing.