Komische Oper Berlin 2019-20 Review: The Bassarids

Sean Panikkar, Günter Papendell Deliver Unforgettable Performances In Fantastic Production

By Dejan VukosavljevicWritten after Euripides’ ancient Greek tragedy “The Bacchae,” “The Bassarids” is essentially a one-act opera with intermezzo. It was composed by Hans Werner Henze to an English libretto by Wystan Hugh Auden and Chester Kallman (who also jointly wrote the libretto for opera “The Rake’s Progress” by Igor Stravinsky).

The opera had its world premiere in Salzburg on August 6, 1966, where it was performed in German, based upon German translation of original Auden’s and Kallman’s text. The first performance that used the original libretto in English took place at the Santa Fe Opera on August 7, 1968.

In the three-month period between June and August 2018, “The Bassarids” was performed in Madrid and Salzburg under the baton of Kent Nagano. The Komische Oper Berlin, one of Berlin’s major opera houses, brought this rarity to its repertoire with a premiere on October 13. The Komische Oper assembled its most powerful forces for the run of “The Bassarids” with the piece directed by Barrie Kosky and conducted by Vladimir Jurowski.

It should also be noted that tenor Sean Panikkar, who took on the role of a stranger (the god Dionysus) and mezzo-soprano Tanja Ariane Baumgartner (in the role of Agave) had sung those roles in Salzburg prior to this new production at the Komische Oper. Barrie Kosky, well known for his inspirational and innovative stagings, promised to breathe new life into this rarely performed operatic jewel.

Why The Bacchae?

Alas, the powerful winds of overall destruction in a bload-soaked tragedy here involved the orchestra as well: what was possible in revenge-driven interactions on stage, and how intensively the performance progressed to series of seismic blows. It was probably on everyone’s mind how this latest rendition of “The Bassarids” would turn out – and with a good reason.

“The Bacchae” has always been considered not just Euripides’ greatest tragedy, but probably one of the bloodiest Greek tragedies ever written. When Henze first received libretto by Auden and Kallman, he was a bit overwhelmed by what he saw. He felt that he was not ready yet to undertake such a big task of composing an Euripidean opera.

After a year he had finally began to craft his masterpiece, and this atonal but well-balanced music collected vast musical echoes from the past – Henze described himself as Mahlerian. “The Bassarids,” however, did not have a musical imprint coming only from Mahler – one could hear subtle, but recognizable musical signatures of Bach or Strauss, even Stravinsky present in the opera as well. The opera itself is structured in the shape of four movements, the first being in sonata form, and ending with a huge passacaglia in the final movement.

The plot of Euripides’ tragedy revolves around the young man (Pentheus) who became king, and his subsequent encounter with his close cousin, the young and angry god Dionysus. Dionysus came to Thebes, disguised as a stranger, for a revenge over his mother Semele’s death. He called citizens of Thebes to revolt against the king, neglect their duties and indulge in endless festivities. Fierce clash between Pentheus and Dionysus would result in utter devastation and destruction of a royal family, and the raid of Greek cities. Political implications were huge, as masses had been led into obsessive, delusional states and psychotic rituals. After all the fuel of the orgies on Mount Cytheron had been spent, massive human debasement followed, with basic moral and social values sinking into a bottomless pit.

The death of Pentheus by the hand of his own mother Agave was the epitome of the tragedy, reflecting the power of prevailing madness. Nobody was spared in this bloody drama, and there was a strong feeling of overall destruction in the end – mainly brought by great singing and dramatic expression.

Henze intimately sensed the echo of a powerful historical relationship between the ancient civilization of an archaic time and a contemporary period. Auden’s and Kallman’s text provided the links he needed to bridge vast temporal spaces, to recreate psychological reference frames common for those times, and explore feedback mechanisms deeply rooted in the history of mankind. The composer truly believed that music could communicate with intimate inner being of every human individual, and relay powerful messages.

At the time when Henze composed the opera, Soviet Union engulfed all of the Eastern Europe with its powerful grip. Whole states had been transformed into gargantuan cults where one leader had been worshipped to the extent of a deity. Ordinary citizens that did not want to be part of the state cult had been persecuted and terrorized. And it was only 22 years after the Second World War had ended – where the formation of another cult resulted in one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history. Euripides’ tragedy also explores powerful and toxic states of mind – ones that could be radically altered by cultish obsessions.

Semi-Staged?

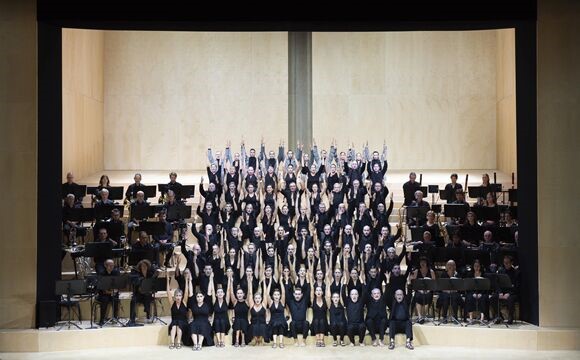

The staging was actually very simple: as parts of the orchestra took their positions to the right and to the left of the stage in an orchestra out-of-the-pit expansion, all that was left was center of the stage, with some stairs. This simple, fixed set was an obvious attempt to portray the entrance to the Royal Palace. The Komische Oper decided to go with the simple solution, leaving out the tomb of Semele in a ruined palace as a part of the set. On the other hand, that was not physically possible to achieve either with such thick orchestral presence on stage.

Overall, this was not an impression of a fully staged production, but rather a semi-staged one. However, this kind of staging did not significantly hurt the general good feeling (though it was felt), as good singing and acting came to the rescue.

The historical timeline of the opera was moved to a contemporary era, with costumes (in the Manichaean black and white manner) clearly indicating that ancient Greeks were recast into some modern setting. Barrie Kosky decided to do the story the Euripidean way – by transposing old times to the current moment, and convey a message about the state of the world as it is now, and as it undergoes endless recycling with the same background motives.

This production also included the famous Intermezzo “The Judgement of Calliope.” It is basically a satyr play written by Auden and Kallman, based on another Greek myth. Original Greek names have been romanized in the text, with Agave becoming Venus, and Autonoe now Proserpine. The Captain of the Royal Guard (played and sung by Tom Erik Lie) became Adonis. Tiresias appeared in the role of the judge. The atmosphere of the intermezzo was highly decadent and outright bizarre. It is a reflection of sexual fantasies, possibly to be reminiscent of orgies on Mount Cytheron.

(Credit: Monika Ritterhaus)

Leading Men

The young king of Thebes, Pentheus, was royally sung by baritone Günter Papendell.

Papendell was completely immersed in the role: his deep baritonal sound was commanding, even frightening at the beginning when he gave royal orders to ban the cult of Dionysus and kill its members. He quickly switched to much more uncertainty in both his voice and dramatic expressions in “Faithful Beroe! To you alone can I open my heart.” It was at this moment of incoming doom where Papendell colored his voice with deep trembling fear, easily traveling across a range of emotions from anguish to the frustration and rage.

In a scene with his mother in a Second Movement (“Mother. Agave. Speak.”), Papendell successfully gave the impression of a deserted child, with painful facial expressions, begging for his mother’s love, and terrified with the fact that she, as well, joined the cult of Dionysus.

And then, just before his first encounter with the young god, he was left totally alone on the stage as all The Bassarids, including his own mother, rallied behind Dionysus. It was a vicious circle for him, and Papendell did very well switching back and forth, from anger to fear and back to anger.

In the first clash with Dionysus, Papendell emanated his frustration and exasperation, in a blazing showcase of confusion – unsure about losing his power, even his head, sensing the approaching threat. He acted violently, hitting the disguised god and throwing him to the ground.

However, as he increasingly fell under Dionysus’ spell, all of these emotions morphed and converged into deep dread, leading him to visit Cytheron disguised as a woman. However, this portrayal had much larger meaning as the female suit he wore was one of his mother’s dresses. At that moment he sounded completely defeated, on his knees, almost reduced to human rubble, as music from the pit portrayed gloom and doom. An abandoned child, betrayed ruler, delusional human being diving into madness – Papendell was all of these at once. It was quite a memorable performance.

Tenor Sean Panikkar portrayed the role of god Dionysus. His voice is very handsome and powerful and his diction was perfect.

In “Keep your sight upon tomorrow,” his lyrical sound caressed these opening notes with a textural subtlety, as delicate warning could have been heard in the background. He came for revenge – and he wanted to make sure that everyone got the message from the very beginning.

In the subsequent scene with Pentheus, he preserved the coolness of body and mind – making his rival more and more frustrated. He was challenging the king, trying to bring him out of his ruler’s shell where he would be much more vulnerable. Panikkar fully adapted his voice for this task – presenting it with a seductive and youthful sound, shimmering in the mist. He switched to a fully defiant mode when singing “My name, King… Pentheus… Acoetes: I am Lydian, a merchant’s son.” As the scene progressed, he gained a more frightening look, pushing Pentheus to the ground, while traversing much of his vocal range. After finally bringing the king out of his psychological armor, he put his hands on the king’s eyes in order to cast a spell on him.

Panikkar proved resilient and robust in the role’s high range requirements with “Naxos, I told my crew, and we set sail. He woke out and wept: Naxos is far astern!” which quickly continues with “The Oaks of Cytheron sway, sway. I follow the God, Pentheus. You shall,” for a cathartic ending of the scene. As he emerged victorious over his opponent, Panikkar radiated gorgeous singing with “He will help you as he helped before. To see. To know.”

The tenor also excelled in opera’s closing scene when he proclaimed the end of the Royal house of Thebes and ordered exile for Cadmus, Agave, and Autonoe. His bronze tone was highly felt in “Yes, I am he: I am Dionysus, soon you shall see me revealed in my glory.”

He put a final stamp on the opera with Dionysus’ closing lines, imbuing a warm and graceful sound, once more proving robustness in high range with “Rise, mother, rise from the dead and join your son!”

Decomposing From Within

Tanja Ariane Baumgartner, in the role of Agave, gave the first glimpse of her warm, ample, dusky mezzo sound with the “Let him go: the blindest of all women thrust upon by Eros, and limpest man.” Baumgartner has a big voice at her disposal, but she also projected it well with no noticeable vocal strain. Mezzo-sopranos spend most of their time singing in the middle range and it was nice to hear Baumgartner engaging in some high notes in “Echion, may we know a reign then long, just and yet more forceful!”

She gave a memorable dramatic performance, as the turning tides after Dionysus’ arrival pushed her to his new cult, abandoning her own son. There was an impression that she was gradually unaware of her own deeds and behaviors, amplified by her lustful dances on Mount Cytheron. Finally, she led the utterly revealing, devastating, catastrophical Fourth Movement in a truly admirable way.

As the final chapter of this modern family saga opened, Baumgartner appeared on the stage in the white dress stained with the red paint (obviously representing blood). She carried a large axe in her right hand, and a plastic bag in her left hand. “Behold the head of the young wild lion, the cub I hunted and have brought home!” she exclaimed, her dark mezzo pierced with subtle staccato as it reflected her unawareness that she had killed her son and decomposed his body. She actually brought his head to the Royal palace.

Stained with blood all over her face, her gestures and facial expressions revealed complete human debasement and torment, as she had really lost her mind, her sound resonating with mixture of anguish and amazement. Overall, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner gave an impressive, heart-wrenching account, both vocally and dramatically, of a woman torn from the inside, herself being morally and psychologically decomposed as well.

(Credit: Monika Ritterhaus)

More Tragic Figures

Jens Larsen did a very good job in the role of Cadmus, with his warm and sonorous bass holding onto a worn-out presentation of the abdicated king of Thebes. Cadmus was seen as a hunched old man, victim of pseudo-religious horrors, cautious and trying to be the voice of reason. Alas, he had not been heard. He sensed what was really coming: his own blood to destroy his royal house (“Could a new young god be my grandson?”) In the end, when Cadmus’ suspicions were finally confirmed, he also gave a very convincing portrayal of a defeated grandfather. In those moments Larsen radiated his full despair and anguish.

Tenor Ivan Turšić portrayed Tiresias as a weak, vain, stupid man, totally consumed by irrationality of religion and blind faith, while he was gyrating to complete the image of a prophet going mad. Tiresias was full of fear: he lost his sight because of the goddess Hera’s rage. Obviously he feared more vengeance from a different god. And that was clearly audible in his voice, especially during Tiresias’ opening lines: “I too would join the dance. I too would wear a fawn-skin.”

Soprano Vera-Lotte Boecker, in the role of Agave’s sister Autonoe, was convincing in her relatively short appearance, also showcase an excellent high range, especially during the prisoners scene in the Second Movement.

Margarita Nekrasova offered her mildly cynical mezzo to portray Beroe, nanny of both Semele and Pentheus.

Rounding It All Out

The chorus opened the opera, telling the story of the abdication of king Cadmus and hailed the arrival of a new king – Pentheus – in a thrilling “Pentheus is our new lord.” It was a full and strong sound to begin with, and hinted at the excellent shape of Komische Oper orchestra under the baton of Vladimir Jurowski.

The english horns, flutes, oboes, and clarinets offered profound musical meaning to initial choral involvement on the stage. The Bassarids – Maenads and Bacchantes – sang in the form of a chorus, narrating the story of human souls deeply immersed in misbehaviors of all kind, from simple murder to orgies, and finally – blissful ignorance. As they sang “We heard nothing. We saw nothing, we took no part in her lawless frenzy,” The Bassarids sent the final message of Henze’s music to the audience, expanding like ripples through time and space. From ancient Greeks, to John Donne and his “Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions” and “For Whom the Bell tolls” – It was a message of yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Synchronization between the pit and the stage was excellent, and Komische Oper orchestration for this occasion (even in reduced form) did very well in bathing the opera house with Henze’s powerful wall of sound.

The Komische Oper in Berlin has successfully staged “The Bassarids” with great singing and profound dramatic expressions from the beginning to the end. It was a semistaged version – but a version definitely worth seeing in a rare display of Henze’s music.