Irish National Opera 2024-25 Review: Mary Motorhead / Trade

Emma O’Halloran’s Brilliant But Emotionally Exhausting Double Bill

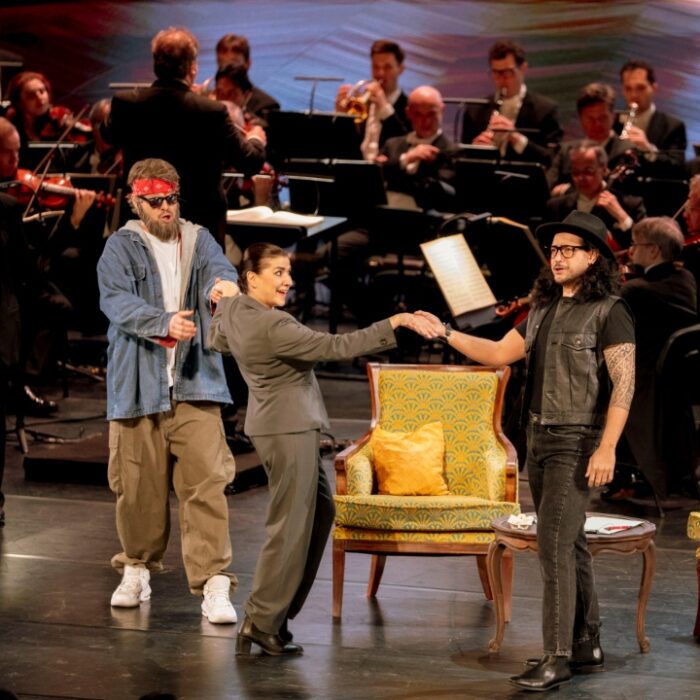

By Alan Neilson(Photo: Ros Kavanagh)

(WARNING: This review features explicit language.)

Irish National Opera recently completed its tour of a pairing of operas by the exciting Irish composer Emma O’Halloran and librettist and playwright, Mark O’Halloran. Both works contain intimate psychological portraits of characters who find themselves in emotionally difficult situations. The first, entitled “Mary Motorhead,” focuses on a young woman jailed for the murder of her boyfriend, while the second, called “Trade,” is based on the awkward relationship between two men, one middle-aged, the other only 18-years-old, who meet for sex in a hotel room.

There was an unrelenting intensity that crossed over from the first to the second opera, and it made for a very uncomfortable 90 minutes of theater; the pain experienced by all three characters was so clearly captured in the music, the dialogue and the performances of the singers, that it managed to force itself into one’s consciousness and emotional fabric with disruptive effects. Days later, it was still possible to recall the pain with acute vividness.

There was nothing easy or relaxing about either piece. There were no light diversions to ease the tensions, which you felt could snap at any moment and cause the dramas to plummet even further into the darkness that the characters already inhabited.

Mary Motorhead

The opera, defined as a ‘monodrama for lyric mezzo-soprano and amplified chamber ensemble’ in one act, was commissioned by Beth Morrison Projects and premiered in 2019 at National Sawdust, Brooklyn. The libretto, written by the composer, was based upon a play by Mark O’Halloran.

The curtain rose on Mary’s prison cell, a confined, empty blue and white space with a single door, designed by Jim Findlay.

Over the next 30 minutes, Mary recalls the events and her ‘secret history’ that led up to her murdering Red, her boyfriend, for which she has to serve 18 years in Mountjoy prison. In what was an emotionally strained reflection, she ripped open the door into her inner world, revealing her deepest feelings and motivations, her own failings and disappointments, things that regular history can never really know. Her monologue was a wild mixture of clarity, self-justification, acceptance and rage in which her emotions swirled around the extremes as she attempted to articulate the bigger truth that lay behind her actions.

The role of Mary fell to Naomi Louise O’Connell, an exceptionally talented singing actress who is able to fully submerge herself into a character, to which she brings intelligent insight, subtlety and nuance. Every word, every line and every note are understood within the wider context and presented to bring out its full meaning, not just verbally but also through her physical gestures and movements.

Her Mary was thus given a multi-layered portrayal, which captured not only her psychological and emotional instability but also her honesty and her genuine desire to communicate her understanding of what caused her to kill Red.

Her Mary was a very, very angry woman; even in her calmer moments she could not completely hide the undercurrents that raged beneath the surface. She blamed the monotony of the midlands, the area in which she was born, shouting out that “they were very lucky I didn’t burn the whole fucking town down.” She blamed her friend Kathleen for abandoning her when her family moved to England when she was a young child. She blamed her father, whom she loved and wanted to impress, for not speaking to her when, as a child, she beat up another girl, who beat her in a race to win a bronze medal. She knows Red’s faults, but through her own loneliness is forced to rely on him; sure, she loves him, and that is why she killed him when he started paying less interest in her.

O’Connell presented it all with an expressively compelling vocal performance that captured her raging feelings as they ebbed and flowed, brought them into abrupt focus in swirling emotional eddies, and allowed them to cascade into overload as she relived Mary’s experiences, masterfully depicting her alienation, loneliness, psychological imbalance, emotional dysfunctionality and atomization, but above all, she managed to portray Mary’s honesty, the brutality of which made it all the more painful to watch!

O’Connell’s excellent acting performance was aligned perfectly to support her singing. Her physical movements and facial gestures, even down to the glint in her eyes when relating certain events, were always carefully measured. She made full use of the available space to draw attention to her captivity, both physically and as a prisoner of her memories.

The lighting designer, Christopher Kuhl, did a fine job in altering the perceived dimensions of Mary’s cell, so that at times it appeared the walls were closing in on her.

With its combination of acoustic and electronic instruments and her use of rhythmically disjointed and fractured lines and erratic movements, O’Halloran’s score successfully caught Mary’s damaged psychological state. It also conjured up the claustrophobic atmosphere of Mary’s confined cell, which added a sense of paranoia that helped precipitate her fatalistic outlook on life. There were sections in which the music took on a more aggressive and assertive form, at one point sounding almost like pop music with its repetitive heavy bass line to which O’Connell bounced around the stage with her adrenaline pumping. Members of the Irish National Opera Orchestra, under the conductor Elaine Kelly, created a sensitive performance with an engaging pace that drew the audience into Mary’s monologue and successfully revealed its interesting textures.

Trade

The opera, also in a single act, is defined as a work for ‘baritone, tenor and amplified chamber ensemble,’ which premiered in 2023 at Abrons Arts Centre, New York. The libretto was written by Mark O’Halloran.

The setting for the sexual encounter between the two men takes place in a boarding house room on the north side of Dublin. Findlay’s stage design was deliberately drab and uninviting, consisting of a bed, a chair and a couple of bedside cabinets with a door leading to a bathroom. Unless the occupants had something to hide and wanted to remain anonymous, it would most likely have remained vacant. And both men had plenty to hide!

This was a sexual encounter in its most vulgar and basic form, a simple monetary transaction in which the older man pays a younger man for sex. The only problem is that the older man has fallen in love and wants more than just sex. For the younger man, it is a trade, nothing more.

Both men share certain characteristics: both have children and difficult family relationships, notably so with their own fathers; each saw himself as heterosexual, and any suggestion that they were not filled them with shame and disgust. Moreover, both felt awkward in the situation in which they now found themselves and were unsure how to proceed.

The work is a detailed, sensitive and painful portrait of their encounter, one that burrows deep to reveal the men’s insecurities, self-deception, shame and pain, as well as their inability to make a meaningful connection with each other or to even understand what was happening. It also revealed the unequal power relationship that existed between them; even if awkwardly expressed, the older man, with his wider experience and superior financial means, dictates the terms of the trade to the younger man, who is naïve, psychologically damaged and broke.

The younger man, played by tenor Oisín Ó Dálaigh, appeared on stage dressed in cheap street clothes. He looked very young, and his adoption of a defensive, nervous demeanor that he maintained throughout the performance was brilliantly crafted. The more the older man opened up and confessed his love, the more uncomfortable he became and gave the impression that he really had no understanding of what was happening, that he was truly out of his depth. His responses to the older man’s questions were met with monosyllabic utterances, a “no” or a “what?” and sounded completely detached. On the occasions he talked about his personal life, he remained distant, ill at ease and confused. There was anger too, especially when the older man tried to breach the divide that separated them, but it was anger created by fear.

It was a truly excellent characterization, one that he supported with a fine vocal interpretation that captured the deep and painful feelings he struggled to articulate. Although many of his lines were short to emphasize his inability to relate to the older man, when the opportunities presented themselves, he sang with an engaging lyricism.

Baritone John Molloy, playing the role of the older man, arrived on stage looking battered and bruised, which he later revealed was the result of a fight he had had with his son, who had reacted violently to his confession of his homosexual liaison with the younger man. He looked disheveled and in a bad way. He was uneasy, nervous and ill at ease and needed to drink cans of alcohol to calm himself. It was a wonderfully sensitive characterization in which one could feel his need to confess his love, his shame at what he was doing, and his inability to form a connection with the younger man. Often, it was difficult to watch, such was the degree of realism he managed to inject into his portrayal. When he asked the younger man to take off his shirt, the awkwardness felt by the two men was palpable.

Molloy’s vocal characterization was expertly rendered. Not only did his singing capture the older man’s emotional complexity, but by emphasizing his Dublin accent, he clearly presented him as having working-class origins, which drew attention to the possible conflicts he was likely to have experienced as a repressed homosexual.

Musically, it complemented “Mary Motorhead” perfectly. O’Halloran’s score again used disjointed and disruptive passages; however, in this case, they were used not only to reflect the broken personalities but also the fractured and difficult nature of the relationship between the two men.

Moreover, as the drama was played out over a wider canvas, the music exhibited a greater degree of variation; there was more time for islands of reflection for which O’Halloran introduced gentle passages of calm, notably in the older man’s recollections of his father; there was more scope for building and relaxing the musical tensions to support the changing emotional relationship of the two men; the melodies, on occasions, seemed to have a more direct impact; the music moved frequently between periods in which it remained in the background, content to capture the mood, with periods in which the orchestra would assert itself; and she also took the opportunity to give greater scope to the musicians to express themselves with short, detailed individual passages.

Kelly once again elicited a strong performance from the Irish National Opera Orchestra, capturing its dramatic and emotional potential.

Both operas were directed by Tom Creed, whose work with the three soloists produced two excellent productions. Not only did he help in bringing out the psychological complexities of their characters, but his attention to detail allied to his sensitive insights made them very believable, very real characters with which the audience could easily relate, even if it was a somewhat painful experience. He was also attentive to the movement and positioning of the singers. In “Trade,” for example, he often had the two men sitting or standing on opposite sides of the stage, reinforcing the lack of connection between them, while in “Mary Motorhead,” he had Mary move around the whole cell to reflect her feelings of being trapped.

At the end of “Trade,” he had the two men embrace each other in what appeared to be an acceptance that they could offer each other at least some degree of emotional support, which seemed to be the wrong choice. Surely, a more brutal ending in which one of the men left the room would have been more honest and certainly more cataclysmic for the older man; after all, it is an inevitability.

Overall, the double bill of “Mary Motorhead” and “Trade” offers an engrossing and thought-provoking piece of theater, although like most successful works, it requires effort; those prepared to put in the necessary work will undoubtedly leave the theatre fully satisfied, albeit mentally and emotionally exhausted by the experience.