Irish National Opera 2019 – 20 Review: Griselda

Vocal Brilliance & Strong Direction Ensure Success For Vivaldi’s Irish Debut

By Alan Neilson(Photo: Patrick Redmond)

The Irish National Opera continues to develop apace. Having been going for less than two years, the company has managed to produce a diverse range of operas that is able to shame more established companies. It could have been excused for playing safe in sticking with popular operas, but it has done no such thing: yes, it has space for Mozart, Puccini, Verdi and the like, but it also has room for rare, contemporary, and new works.

This year, the company has showcased such works as Dennehy’s “The Second Violinist” and Irvine’s brilliant “Least Like The Other.” It is a company which, under the direction of its founder and Artistic Director Fergus Shei, knows where it is going, and has the determination and energy to deliver.

Now it has turned its attention to Vivaldi, a composer who to this point has never had an opera performed in Ireland, with a production of his 1735 work, “Griselda.”

Trials Of Worthiness

Written to a libretto by Apostolo Zeno, revised by Carlo Goldoni, it is an unconvincing story of King Gualtiero, who is deeply in love with his wife Griselda, and is suffering from a discontented populace because they consider her to be too low born for such a position. His solution is to subject her to a series of cruel trials in order to prove to the people that she is indeed a noble person, although he has doubts as to whether he will be able to see it through. She is therefore banished from the palace, while Gualtiero prepares to marry a more suitable woman; she is also separated from her son and subjected to the amorous attentions of Ottone.

Needless to say, everything works out perfectly; Griselda faces the situation courageously, displays a noble heart, and is accepted by all, although unsurprisingly certain tensions remain.

Tom Creed, the director, did a fine job staging the work. While managing to remain faithful to the text, he was able to create a presentation which focused on Griselda’s suffering, set in a modern day context in which the more ridiculous aspects of the plot did not distract from her situation. Rather he used them to frame her pain, giving them a light comedic or ironic veneer, which had the effect of isolating Griselda further, and ensured that the audience did not have to struggle to reconcile her very real suffering with the very unreal situation in which she was placed.

Creed used a two-tiered set, designed by Katie Davenport, to contrast the brutality of the street, to which Griselda is consigned, with the secure world of the place, protected by security guards and cameras. In fact, the invasive nature of modern surveillance lies at the heart of Creed’s production; everything which happens is recorded by cameras and exposed in the media. Video screens are positioned down one side of the stage so that we can see everything that happens onstage and offstage. There is no privacy, and everyone is open to judgement by the anonymous mass, cleverly connecting the themes of Vivaldi/Goldoni’s 18th century conception to the present day.

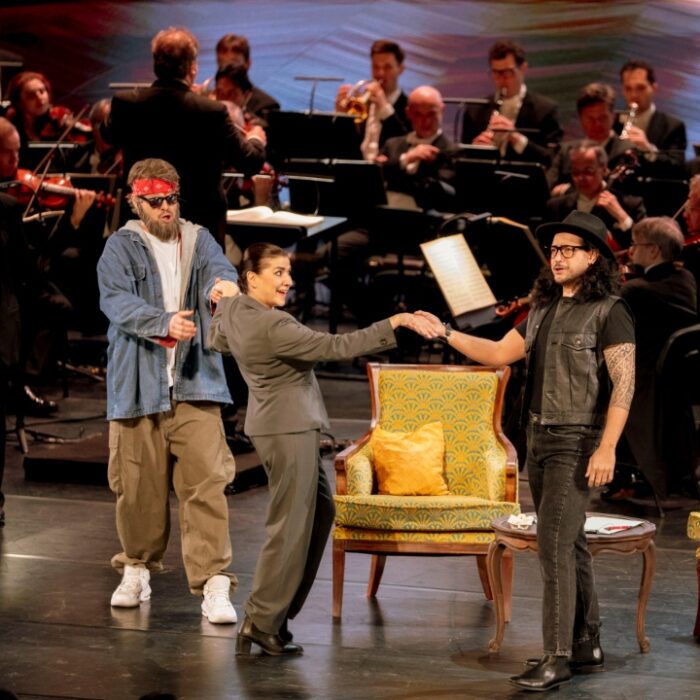

Davenport was also responsible for costume designs, which were not simply used to define the status of the characters, but also to cast them in an ironic light. Gualtiero, the King, is given an over-the-top golden suit, occasionally with a large crown and ermine collar. Griselda, however, when she is thrown out onto the street, is clothed as a typical homeless person, in a miserable tracksuit, which maintains the focus on her misery.

Dramatic Worthiness

It has been argued that Vivaldi’s operas lack the necessary dramatic power to hold the stage, but over recent years this is being increasingly disproven, and this production from Irish National Opera offers further evidence to that effect. In fact, under the musical direction of Peter Whelan, the Irish Baroque Orchestra produced a rendition which emphasized the work’s dramatic character, which was reflected in the performance of the singers, and which combined successfully with Creed’s direction to create an engaging piece of theatre. Nor did Whelan’s interpretation neglect the beauty of Vivaldi’s music which, for the most part, he elicited successfully from the orchestra comprised of 11 players; however, the sound was at times somewhat dense and did not always fully explore the wonderful textures of Vivaldi’s score.

The high quality cast was led by mezzo-soprano Katie Bray in the role of Griselda. She gave a detailed and compelling performance, capturing both the regal nature of the character as well as her deep suffering. Every line was carefully constructed, with each word given appropriate attention; coloring, accents, dynamic shadings and emotional stresses were all intelligently employed, in what was an expressive reading.

Recitatives and arias were given equal weight and delivered with clear articulation and emotional honesty, and supported by her fine acting ability.

The role of her morally weak husband, Gualtiero, King of Thessaly, was essayed by tenor Jorge Navarro Colorado. In what was a subtly-drawn portrait, Colorado depicted his character as a superficial individual, prone to posturing, rather than deep emotional engagement. Possessing a pleasing timbre, his singing was smooth, consistent and largely understated. He made good use of finely placed ornamentations and built his character well, managing to bring sense to what was an often indecisive, conflicted yet largely decent person.

Soprano Emma Morwood, was cast in the role of Constanza, Gualtiero’s proposed replacement for Griselda, who herself is in love with Roberto and arrives at the palace with him in tow. Dressed for most of the evening in a short silver sequined dress, Morwood portaryed Constanza as a fairly simple, even dim, blond, with a good heart, who easily gained the sympathy of the audience. Her singing was vibrant and bright, with flashes of color. Technically secure she danced her way through the role, her coloratura beautifully integrated into her emotional outbursts.

Roberto, Constanza’s man in tow, was played by countertenor Russell Harcourt and made a fine impression in the role. He possesses a wonderfully pure clear sounding voice with an appealing timbre, although like many countertenors it lacked coloring. This did not prevent him, however, from injecting the necessary presence into his singing, which enabled him to successfully capture Roberto’s changing emotional states. Harcourt’s singing was also notable for his excellent vocal control.

Two Vital Trouser Roles

Two male roles, Ottone and Corrado, were originally cast for castrati. Rather than casting them for countertenors, as in the case of Roberto, or for females voices, but played as trouser roles, a decision was taken to use female singers and to play them as females, reflecting the enlarged roles played by women in modern day society.

Raphaela Mangan was therefore cast as Gualtiero’s personal assistant, Corrado. A relatively small role, Mangan made the most of it, portraying her as an efficient and hard-headed professional. Her singing was similarly set; strong, focused, strident, but expressive.

In the role of Ottone, who is Gualtiero’s Head of Security and also in love with Griselda, was mezzo-soprano Sinead O’Kelly. Occasionally, a singer produces a shock performance, and this is exactly what O’Kelly produced.

Initially, her solid, almost workmanlike, singing did little to capture the attention, but her aria which brought the first act to an end was electrifying. Kicking off her dress shoes, she put on a pair of boots and let rip. During the second act there was no let up as she continued in the same vein.

O’Kelly has strong, flexible voice, with a colorful pallet, which she used with intelligence and imagination to develop characterization. She moves up and down the scale with ease, which she furnishes with an array of colors and dynamic accents. Her phrasing is technically secure, wonderfully agile and aligned precisely to the dramatic position.

Moreover, her acting was also of high quality; at times she looked absolutely demented as she raged at Griselda’s rejection, deliberately going just a little too far so as to expose the underlying humor in her behavior. O’Kelly, currently a member of the International Opera Studio at Opernhaus Zurich, has enormous potential, and it is very likely that we shall be hearing a lot more of her in the future.

Overall, Vivaldi’s first-ever opera to be performed in Ireland can be considered to be an outstanding success, and a testament Irish National Opera’s ambitious programming. It not only provided further evidence that Vivaldi’s operas are dramatically strong, and can be successfully staged in the 21st century, but did so with style in a production which was engaging, and with singing which was first rate.