How Eugène Scribe’s Genius Shaped Meyerbeer’s Greatest Operas

By David SalazarEveryone knows the composer. Verdi’s “Otello.” Rossini’s “Il Barbiere di Siviglia.” Etc. But few pay attention to the writer, the person who actually provides these great geniuses with the text for their music.

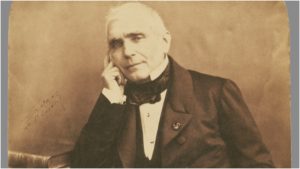

Eugene Scribe, born on Dec. 24, 1791, is one of the most notable librettist in all of opera, and yet he doesn’t quite come up in conversations as often as one might expect. Of course he was rather present throughout the era of French grand opera and is one of the men responsable for the success of Meyerbeer. In some ways, he is the man behind the great composer’s greatest feats, writing the libretti for Meyerbeer’s four finest operas – “L’Africaine,” “Robert le Diable,” “Le prophète,” and “Les Huguenots.”

He also wrote Verdi’s “Les Vêpres Siciliennes,” which is indebted to the work of Meyerbeer. He wrote a ton of other libretti and some of his plays, most notably providing the subject matter for “L’Elisir d’Amore,” “La Sonnambula,” and “Adriana Lecouvreur,” all of them repertory staples in their own manner.

But let’s turn to the Meyerbeer-Scribe partnership and why it allowed the composer to flourish in ways few others have.

Social Questioning

Scribe’s libretti for Meyerbeer are brilliant for their ambiguous treatment of major subject matter. Religious institutions are constantly called into question, particularly in “Les Huguenots” and “Le Prophète.” And the beauty of all this is that Scribe sets the intimate stories against massive tableaus that allowed Meyerbeer to engage in stories of major thematic challenges on a grand scale.

Ambiguity of Character

Not all the characters of Scribe’s creation fit this mold of complexity and ambiguity. Some are stock characters in fact that just go through the motions of romantic hero or heroine amidst a more complex backdrop. But when Scribe gets it right with the characters, he really nails it. Such is the case in “Le Prophète” where the main character Jean de Leyde cannot even be called a hero, his motives often questionable and his actions moreso. Ditto for his mother Fidès and all the Anabaptists. The opera works so well because of this ambiguity that keeps the audience constantly guessing in which direction they are headed.

Context

The social questioning is essential, but what Scribe did so well was establishing his world within historical frameworks. He sets “Prophète” in a feudal society raging with religious war. The same goes for “Les Huguenots.” “L’Africaine,” or “Vasco da Gama” is showcased during an era of colonization. “Robert le Diable” also features during the middle ages. The most important aspect of this decision isn’t so much how it allows the two to discuss relevant societal issues, but to express how those very problems remain in the society of today. Instead of using his time periods to evoke a romantic era that is often fantasized about, Scribe and Meyerbeer emphasize that those eras weren’t all that different from the way they are in their particular time – full of religious feuding and division, false prophets, and unruly colonization.