Glyndebourne Festival Opera 2024 Review: The Merry Widow

Cal McCrystal’s Exciting New Production is an Uneven Affair

By Benjamin Poore(Photo © Glyndebourne Productions Ltd. Photo: Tristram Kenton)

There was much to fuel the excitement around a brand new production of Franz Lehár’s “The Merry Widow” for Glyndebourne Festival Opera this year. It’s the first time the work has ever been mounted there, and it’s always a treat to see what the slickly-oiled operatic operation, with its six weeks of rehearsals, can do when faced with a ‘lighter’ work such as this. It was to be performed – another departure – in English too, in an equally new version of the libretto, far more than a mere translation, by Marcia Bellamy and Stephen Plaice.

Director Cal McCrystal also has much to recommend him in this repertoire. Barnstorming, imaginative and (most importantly) very funny visions of “Iolanthe” and “HMS Pinafore” at English National Opera in recent years have seen him anointed the king of physical stage comedy; his version of “Le comte Ory” for Garsington last year was similarly feted. His stage and screen background has made his shows wriggle with life and got the audience howling; he was responsible for West End Hit “One Man, Two Guv’nors,” the physical comedy in the “Paddington” films, and has also worked with Cirque du Soleil.

On top of this, the London Philharmonic Orchestra are conducted by John Wilson, who has an iron-clad reputation in so-called ‘light’ music, swooning his way through Rodgers & Hammerstein, G&S, and the slippery, melodious repertoire from stage and screen from the early-to-mid twentieth century. A star turn from the lady of the house herself in the title role, Danielle de Niese, put excitement at fever pitch. A pity it turned out to be a bit of a misfire, then.

Illuminating Details

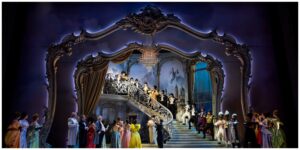

It’s not, by any means, a complete disaster. The design, by Gary McCann, is faultless and oozes with luxury and expense. The Pontevedrian Embassy, where the myriad suitors and diplomats will try and secure the fortune of the latterly widowed Hannah Glawari, is a luscious three-framed design around a staircase straight out of Disney, awash with purple and gold, and beautifully lit. The rear of the Glawari villa, with shades of Versailles is similarly glamorous, and Maxim’s is a rich, erotic red, finally letting loose the sexual energies that bubble underneath all those waltzes and wobbling strings; you can almost feel the softness of the velvet coming off stage. It thrills the eye. The Golden Age of Hollywood setting feels like a treat, and cements the relationship of operetta’s melodrama with the iconic years of the silver screen; the mise-en-scene, as the program book suggests, is inspired by the glossiest of “Vogue” photoshoots.

The dancing, too, is marvelous, with choreography by Carrie-Anne Ingrouille. Not just the athletic Can-Can of the final act, and the waltzes, which have an exacting, balletic sway and whisper of erotic promise, but the bad dancing given to both baritone Thomas Allen’s Baron Zeta and actor Tom Edden’s Njegus, which has wonderful mannerisms and rightly tickled the audience. There are some witty turns in the dialogue – a passing comment on setting up the Pontevedrian National Opera (PNO) pushed the satirical button; the new text worked best when it leaned into Marx brothers-style wordplay and absurdity – a McCrystal specialty. The production as a whole could stand to tap into the characters’ soft underbellies a bit more, but there were some sudden shafts of vulnerability and moments of pathos, especially in Danilo’s struggle to tell Hannah he loves her in Act three.

McCrystal’s slapstick feels at home in the dementedly upside-down universe of G&S and Rossini, where the characters can’t believe they’re in the action – but for Lehár’s slightly world-weary, lived-in characters, whose feelings are traced with authenticity and tenderness, one wonders to what end one of the character’s cavorts with an inflatable sex-doll in a greenhouse. Such silliness is very funny, for sure; so too was a brilliantly executed sequence with a drunk Count Danilo tumbling down the stairs and then being roused ineffectually by Njegus. But how apt is it in this show?

Tom Edden, as the non-singing part Njegus, opens Acts one and three with a stand-up routine whose pacing hadn’t settled by opening night (understandable given these things must be perfected with an audience present). He is charming and boisterous and plays the high camp naughtiness of the whole thing with real dash, though the jokes themselves seem to belong rather oddly to the TV variety comics and clubs of the 70s and 80s, which feels tonally at odds with this rather wistful, bittersweet piece; it feels like a pre-show Revue to warm us up has crept into the piece itself, and disturbs the narrative flow; it’s all too easy to forget about the business with the fan or who is meant to be seducing who.

It’s a very slight work, and, perhaps anxious about people not getting their money’s worth, McCrystal et al have loaded it with dialogue – the opening night finished some forty minutes after the advertised time, which may well put a train-chasing audience on edge. One of McCrystal’s favorite gags – and it is a delightfully absurd one, as seen in previous shows – is to have a musical refrain with a dance routine repeat and accelerate until one of the characters collapses in exhausted fury. It’s fun once – but we hardly needed it twice, given how much of everything else there was.

The dialogue itself – quantity aside – never quite sparkled, with some inaudible and shapeless delivery. It was oddly set, too, with chunky English text failing to skip across the effervescent music bubbling up from the pit; given the length of the dialogue scenes, the musical felt rather sidelined. McCrystal, as noted, has a great track record in operetta. But a show like this, when so much depends on the pacing of the dialogue and the honing of its delivery – activities that so often leave singers exposed compared to straight theater actors – needs a couple of weeks of honing in previews, which simply can’t be the case in opera. At the moment it feels like two shows occupying the same stage, one weighed down by extraneous ballast.

Musical Highlights

But when the music does come it is sensational. John Wilson and the LPO treat it with care and diligence; they show the glue that binds the Viennese language of operetta to the music of the Hollywood weepies and Rodgers and Hammerstein. The strings have a fast, intense vibrato, straight off the silver screen; woodwinds are mischievously nimble. The brass in the brilliant Act three can-can in Maxim’s are brash and joyous; a complete tour-de-force. The Vilja Song, complete with onstage band of guitars and tamburicas, was an absolute riot – silly, smoldering, and tight as a drum.

And how was the singing? Mostly very fine. Danielle de Niese had a rather pinched first act, sounding a little reedy, something echoed in rather stifled delivery of the dialogue; as the show went on, though, her instincts as a stage animal seemed to kick back in, with a compelling physical presence too. We were reminded that she has given a terrific turn on this stage as Adina in “Don Pasquale” and is a seasoned performer in musicals in the West End. The sound found its focus in Acts two and three; the Vilja was zesty and bursting with energy. As the opera approached its emotional denouement, de Niese found tender, wistful colors and timbres in the voice, and had the audience in the palm of her hand.

Her counterpart in Danilo was sung by Germán Olvera, who, whilst less compelling in the dialogue scenes, has a rich and liquid baritone used to stylish effect, especially in his opening aria, where he sings of the pleasures of Maxim’s – the lightness in the voice managing to be both carefree and fragile; he darkened as the emotional temperature (somewhat) rose in Act two.

Soraya Mafi’s Valencienne glittered throughout, playful and flexible; Michael McDermott’s Camille de Rosillon, her lover, has a tenor well-calibrated to balance lyric flexibility with core power, with a sprinkling of sparkling squillo. Thomas Allen, a stalwart of the British opera scene, might be an octogenarian, but his Baron Zeta was crisp and characterful – he is as nimble as the rest of the cast and could teach them all a thing or two about delivery and pacing. He was graceful and, fleetingly, vulnerable, though also able to turn on the head of a pin back to a blustering civil servant. The ingredients are all there – but this version of “The Merry Widow” feels like it needs a little more time in the dramatic oven before we get the perfect Viennoiserie.