Glyndebourne Festival Opera 2023 Review: A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Peter Hall’s vintage production still casts its spell

By Benjamin PoorePhoto: © Glyndebourne Productions Ltd. Photo: Tristram Kenton

Normally, ‘heritage’ productions make me nervous. The established stagings summon to mind lumbering Zeffirelli-esque spectacles and unwieldy, moth-eaten costumes. Opera houses resting on their artistic laurels, unwilling take artistic risks. The ingrained conservatism in the opera business that could even prove fatal for the art form.

But, Peter Hall’s production of Benjamin Britten’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” at Glyndebourne, shows how some stagings really do earn their keep. It is over 40-years-old and sprinkled with the fairy dust of history. Countertenor James Bowman, who first sang Oberon in the show, recently died in March of this year. Peter Pears, who attended the 1981 opening, lamented that Britten had not survived to see it. He felt the show to be perfect. Bernard Haitink, another recent loss to the music world, conducted the production premiere. There were huge shoes to fill in this 83rd performance of the piece in Sussex, which has been running since before many of the cast members were even born.

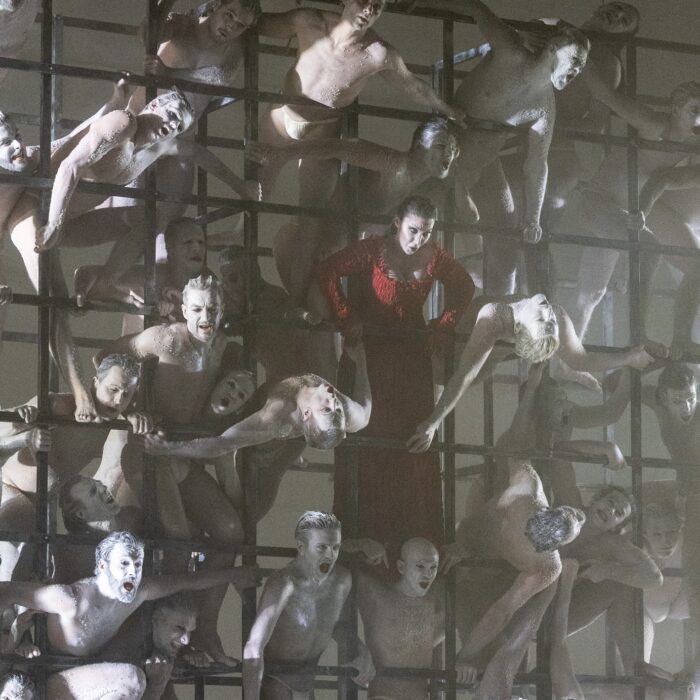

Hall’s theatrical imagination is brilliantly evoked by revival director Lynne Hockney and so acute that the show never feels like a museum piece, even decades later. John Bury’s designs are at its stirring, rustling center, in an ingenious blend of naturalistic and unreal elements. The forest is an uneasy place, full of uncanny trees with realistic branches and leaves that twitch, shake, and encroach thanks to experienced stagehands wearing all black. Their impact is heightened by the fact that they remain miraculously still the rest of the time, only coming to life in the most unsettling way. The forest itself is watching. It is a sinister idyll suddenly gleaming in the moonlight before darkness settles again. Puck sometimes glides in on a swing. His evocation of Watteau perfectly encapsulates the opera’s dark rococo licentiousness.

Bury and Hall’s vision is breathtakingly atmospheric and smart. Even if the intellectual touches are light and fairly traditional. The semi-visibility of the stagehands recalls the play’s own awareness of its artifice that is heightened by the mise en abyme of the Mechanicals’ play. The costumes are “Tudorbethan” and roughly situated in Shakespeare’s era. Tytania and Oberon’s preternatural get up might also belong to the era of glam rock and punk with all the leather and countercultural estrangement. The fairies’ realm is perhaps a metaphor for the secret magic of subcultures. Details are finely studied. Even the ears on Bottom’s ass head mask wiggle in a way that is both disconcerting and strangely cute.

It’s not a wildly philosophical production of a work whose themes offer much to chew over, but its theatrical thrall is irresistible. As both director and choreographer, Lynne Hockney has the Mechanicals’ play-within-a-play down to a tee. The physical comedy is exceptional. Special highlights include Pyramus’ death scene, Thisbe’s stage fright, and the fussy business at the side of the stage from director and rest of the “cast.” The broader sense of all the characters’ established physicality, whether it be the pairs of lovers, Mechanicals, or fairies, is what allows the opera’s musical gear changes to work so seamlessly onstage as well.

Exultant & Powerful

Tim Mead sings an exultant Oberon, even if there are a few misfires in the treacherously low-lying part. Otherwise all is well. His voice is of an imperious power and clarity. It is never bland in its exactitude, unlike some countertenors. There is a quality of rawness and a certain acidity that brings some erotic edge and physical urgency to this supernatural figure. “I know a bank,” with its unearthly combination of celesta and harpsichord was transporting. Liv Redpath’s Tytania was similarly radiant and soaring over the orchestra.

Many plaudits should go to young Oliver Barlow, as Puck. Britten’s vision of the role came from Scandinavian child acrobats. In his role, Barlow teems with life in both voice and action. His zipping about the stage and pea-shooting lines into the auditorium. He had energy and charisma in spades. The audience was in the palm of his hands. No wonder they applauded so enthusiastically when the show came thundering down.

The quartet of lovers performed by Caspar Singh as Lysander, Rachael Wilson as Hermia, Samuel Dale Johnson as Demetrius, and Lauren Fagan as Helena, are given more conventional music by Britten. It reflects on their more earthbound and normative journeys. Singh is well at home in Britten and finds a happy mix of flexible lyricism. There are always shades of the Lieder recital in these pieces and a sheer mettle when the arguments heat up. Fagan and Wilson complemented each other well. They bring a special intensity to their quarrel with Fagan gleaming vituperatively as the “painted maypole,” while Wilson’s coiled mezzo snarled.

The Mechanicals are led by old hand Henry Waddington as Quince. He is amiable and earnest as the director of their play. James Way was in superb comic form as Flute, while mixing vocal playfulness with excellent movement as the reluctant heroine of Pyramus and Thisbe. Patrick Guetti made fine use of his considerable stature and cavernous bass as Snug, with wonderfully flailing limbs and a pantomime aspect when giving his Lion.

None of these performances, though, are mere scenery-chewing. It’s the kind of comedy born of tenderness and affection. The silliness underwritten by a keen sense of all the characters is rounded. There are no small parts, only small actors, as the saying goes.

Brandon Cedel’s Bottom has many faces. At times, he is soft-grained and suddenly poetic. In the great Act three soliloquy, he floated unearthly high notes. Other times he was bullish and bursting with baritonal excess, like in the casting scene. His manifesting of this mutability is so important to the opera’s inner alchemy and Cedel did it with aplomb. Dingle Yandell was in luxurious voice as Theseus. He was commanding, rich, and invitingly sensual. We first meet him, and Rosie Aldridge’s equally splendid Hippolyta, sharing a deep kiss.

Gusty & Exuberant

The Trinity Boys Choir, no strangers to this production, excel in the uneasy whole-tone harmonies that summon Britten’s enchanted woodland. They were exuberant young actors, animated and precise. But their musical range is even more impressive, otherworldly and poised in the opening chorus, and glinting with mischief, even threat, elsewhere when they turned up their vocal brightness. The four soloists drew from their ranks excelled in their Act three scene with Bottom. As the opera’s only chorus, they brought as much vivacity and variety to the world of the opera as any gang of seasoned adult choristers would.

Dalia Stasevska conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) with enviable alertness to the many details of Britten’s score. It was often gutsy and astringent, like a musical forest teeming with wriggling life and musty smells. Strings, especially lower down, were all half-light and shadows suddenly gleaming and disappearing. The percussion was, well, Puckish, with woodwind and harpsichord providing abrupt shards of illumination. Stasevska’s care over the score, combined with meticulous work from the LPO, pulled out both the score’s erotic sensuality and its lingering sense of threat. Special mention should go to the LPO principal trumpet for solos of acrobatic brilliance.

Opera companies should never be afraid of change. But this is one of those productions that shows how tradition can invigorate rather than confine. Surely it will continue to run for as long as Puck makes good on his promise to “restore amends.”