Festival d’Aix-en-Provence 2023 Review: The Threepenny Opera

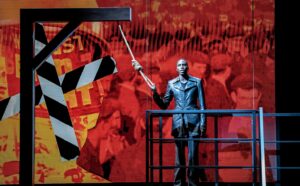

By João Marcos CopertinoPhoto: © Jean-Louis Fernandez

When a ticket to “The Threepenny Opera” costs three hundred euros, it is already evident that someone has not read Brecht properly.

Thomas Ostemeier, the director of this Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill “opera,” is an interesting figure. German by birth, he has been very popular in Paris for his work with the traditional company Comédie Française. Earlier this year, I saw his staging of Shakespeare’s “King Lear.” It was interesting, though very alienated from the tragic poetry (or tragedy) of the Bard. A very specific demographic believed themselves to be witnessing the reinvention of the wheel. I was pleased by the performances, but frustrated with the result overall. Lear returns to the throne very much alive, next to a reluctant Cordelia. Sometimes people just do not get that tragic and tragedy are related.

The most impressive thing, however, was Ostermeier’s sadism. He forced his audience to endure all of his almost three-hour spectacle without even a brief entr’acte. Now I understand why. Ostermeier avoids having intervals in his plays because he is afraid half of the audience will leave in the middle. In this three-hour “opera,” hardly a minute passed in which one could not see a conspicuous theatergoer leaving the Théatre de l’Archevêché for good. The staging was not vulgar, and not even overly radical. It was simply boring as purgatory.

Facing Brecht

Who am I to teach Ostermeier Brecht? No one. In the world of public letters, I am lower than the sands at the bottom of the Dead Sea. Ostermeier has a very long and solid career. He has shown himself capable of pulling out many good spectacles. I saw some that were impressive. Maybe this Brecht is not for him, even great directors can mess things up once in a while.

But I am tempted to believe that Ostermeier’s problems facing Brecht are symptoms of some systematic problems that arise when there is too much space for some people, and too little time for individual productions. In a career of so much prestige and public recognition, sometimes it becomes easy to not actually read things through or review what is thought to be fully known.

Brecht might be accused of being a proselytizer, but Ostermeier makes the play so much more that the production derides the text completely. The result of attempting to make an already didactic work more didactic, however, was to empty it of any revolutionary content, making it about as revolutionary as King Charles III drinking his tea at Buckingham Palace.

The other problem is that Brecht’s texts expose some of the inner problems of dramaturgical rhythm that the particular style of Comédie Française leads them to ultimately face. The company is one of the cheeriest things of my life in Paris, but Brecht has always been a tough call for them. Last December, they staged “Galileo’s Life” in a revival of Éric Ruf’s staging. All of Brecht’s demands were fulfilled and Hervé Pierre was the most moving of all Galileos. However, it was a Brecht à la Comédie. They staged him just as they do Chekhov, Büchner, and Molière. Ostermeier tried to change that, but the result is even more conservative than expected. The new translation of the Three-hundred pound opera, by Alexandre Pateau, though slangy, is not bad. But, it does not reveal the best of Comédie’s talents, or Ostermeier’s capacities. They are the theater company that reads Victor Hugo poems on YouTube with such crystalline French that even my chihuahuas can understand and quote it to my old-dead gran. I personally recommend watching Florence Viala read Baudelaire, just to get an image of what a Comédienne can do in their natural environment. It works and it carries meaning.

And the Music…

Nobody expects Kurt Weill’s songs to be sung operatically. Actually, in theory, the best part of having classically trained actors is their capacity of joining a certain form of vocal projection with linguistic expressivity. Lotte Lenya, Weill’s wife, Bond villain, and most importantly the first Jenny, the prostitute that continuously betrays Macheath, was never fully in tune when she sang. That was okay, since her singing expressed emotion. With her, music was never boring.

After some decades, Weill found more in-tune performers. Brecht-Weill’s songs have their long, democratic, tradition of how they should be sung. The good renditions are many, each with their specific qualities. The bad ones, however, have always failed by ignoring musical and textual phrasing. Opera-lovers might find much to admire in Teresa Stratas’ recordings with their intimate acting, or in Cathy Berberian’s thousand voices. Patti LuPone proves that Brecht and Broadway can work sometimes. In Portuguese, Brecht-Weill became a counter-cultural resource for artists like Thiago Pethit and Cida Moreira. No kings of intonation, but extremely expressive.

The cast of Comédie could neither reach the technical level of professional singers, nor manage to sing with proper expression. Maybe the only one who could actually sing, bringing expression to the text, was the charming Claïna Clavaron, who sang Lucy.

What impressed me is how even the most talented of actors seemed clueless about how to sing. Véronique Vella repeated the same musical phrasing for every iteration of a phrase in all her songs. Birane Ba has all the charm needed for the character of Macheath, but beyond issues in intonation, his voice seemed infantile and fragile in the higher notes. This effectively killed the buzz. And, Marie Oppert confounded affectation with meaning. A few moments with Cristian Hecq worked, but he is one of the most exciting comedy actors in France.

It is interesting to note that the play worked better. That is, it was less boring and more comprehensible when the actors were improvising. In these moments, we see how the Comédie’s (in)famous classicism actually pays off with strong actors. The problem is who directs them.

The orchestral group, Le Balcon, works properly under the auspicious conducting of Maxime Pascal. They did not save the night, but they at least gave strong musical support to help non-singers do their job. Though, maybe Pascal could have coached the singers more.

Less than two weeks ago, Brazilian theater director José Celso Martinez Côrrea, kindly called Zé Celso, died. He burned to death in his apartment. He was 86. The whole night, I kept thinking about how much greater this performance would be if he had directed it. Zé Celso was a revolutionary who truly understood the political commitment of theater and music. He staged works ranging from Brecht to Oswald de Andrade to Shakespeare with intense furor. Last December, I saw an homage to Villa-Lobos at his theater, the Oficina. It was not professional singing, but there was life and meaning in it. A hope for a better world, a mere expectation that moments passed within the walls of a theater can make things different. More than an idle comparison between Ostermeier and Zé Celso, it’s just a tear that I drop thinking about how special theater, especially Brecht, can be.

However, no amount of money or attention in Aix-en-Provence managed to make “The Threepenny Opera” that is not even worth a three-dollar bill.