Deutsche Oper Berlin 2024 Review: Der Ring des Nibelungen

By Tony Cooper(Photo by Bernd Uhlig)

I’m back in Berlin, a city I favor and enjoy so much, ready for yet another Ring cycle at Deutsche Oper, a large, comfortable 1850-seat theatre boldly designed in the Modernist style and simply ideal for large-scale productions. And none comes much larger than those penned by Giacomo Meyerbeer, Richard Strauss and Richard Wagner

Therefore, with my mind furiously on fast rewind, I fondly recall seeing the final performance of Götz Friedrich’s monumental (and well-loved) “Cold War” Ring that lived on Bismarckstraße for an astonishing amount of time – 33 years, in fact, from 1984 to 2017. A pretty good innings all round!

As a matter of fact, the director of Deutsche Oper’s current Ring, Stefan Herheim, follows in his wake as he just happens to be a disciple of Götz Friedrich and studied under him at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg from 1994 to 1999. Surely, a bit of the Old Master has rubbed off on him!

And Götz Friedrich (as did Harry Kupfer) crafted their trade working as an assistant to the well-respected Austrian-born theatre/opera director, Walter Felsenstein, the iconic boss of East Berlin’s Komische Oper in the early post-war years.

His philosophy was that opera went beyond singing to encompass music-theatre: the intersections between music, sound and theatrical performance. Therefore, his productions focused on pure dramatic and musical values which were thoroughly researched and, indeed, finely balanced.

Such philosophy, I feel, defines Stefan Herheim’s direction. He pulls no punches and pays full attention to detail often incorporating ideological and historical references in his work. For instance, his celebrated 2009 production of “Parsifal” at Bayreuth, which I greatly enjoyed, used Parsifal and the search for the Holy Grail as a metaphor for the development of Germany as a Christian nation.

He sparked controversy, though, when depicting the country under the absolute rule and order of the National Socialists. Strong and chilling stuff, maybe, but it was daring stuff nonetheless that showed his directorial style and prowess causing a few raised eyebrows here and there. However, I admire directors such as Herheim who push boundaries while challenging the status quo in opera especially when it comes down to Wagner.

Consequently, if Friedrich’s Ring focused on the big issue of his day, nuclear warfare, Herheim follows suit and his Ring (receiving its second outing following its full cycle in 2022) focuses on the big issue of today, the refugee crisis, a subject hitting the headlines on a day-to-day basis.

Das Rheingold

Refugees, in fact, find themselves at the forefront in the opening scene of “Das Rheingold“ personified by a weary group of travelers trekking slowly, silently and forbiddingly across a bare stage except for a full-size black grand piano bundled up a corner soon to make its way to centre stage. Clutching an odd assortment of battered old suitcases, they could have been spinning stories about the legend and culture of the Ring or, perhaps, searching for their golden opportunity in life. Who knows?

But watchful as ever and lurking in their midst and leading the tribe is none other than the great wanderer in life himself – Wotan. Breaking loose from the human chain, he edges towards the piano, knocks out a chord from the opening bars of “Rheingold,” the orchestra immediately takes over and the “Game of the Gods” begins.

And the formidable role of Wotan, Game Master extraordinaire, boss of the whole damn shooting-match, fell to Scottish-born bass-baritone, Iain Paterson, who perfectly fits the part – vocally, visually and physically! He’s a natural and so relaxed on stage often adorned by a feathered-winged helmet so popular in Wagner’s day thereby offering a nice touch by Herheim in revisiting the past – something that he’s very fond of doing.

From my standpoint revisiting the past, I happily recall Paterson delivering a superb performance of Kurwenal in Katharina Wagner’s riveting and intelligent production of “Tristan und Isolde” at the 2015 Bayreuth Festival working alongside German mezzo-soprano, Christa Mayer, as Brangäne.

Also lurking within the refugee column (maybe keeping a watchful eye on Wotan!) is the formidable trio of Rhinemaidens comprising Lea-ann Dunbar (Woglinde), Arianna Manganello (Wellgunde) and Karis Tucker (Floßhilde), the true guardians of the hoard of gold that the Rhine harbours.

A well-schooled team, they lovingly relate the legendary story of the power and the magical properties of the Rhine’s gold in an impressive and tantalizing performance. While lugging into their careless talk about the forging of a ring, Alberich’s all eyes and ears dazzled by the sight of the gold.

Therefore, renouncing love and cursing life (the wager of possessing riches beyond the dreams of avarice!) he happily screams off with the gold leaving the Rhinemaidens forlorn, screaming in agony. There is, of course, a lot to scream and shout about in the unfolding story of the Ring.

In essence, no one screams and shouts more than Wotan’s long-suffering wife, Fricka (Goddess of marriage) who with her sister, Freia (Goddess of youth) arrive on the scene in a more eloquent way than her husband jumping from the refugee column. They graciously come from the bowls of the piano resembling a couple of finely-sculptured porcelain figurines on a five-tiered wedding cake.

Smartly attired in long-flowing white dresses, they look radiant in appearance as befitting their regal status with Fricka (standing) grooming her sister’s hair while Frei (seated) pampering herself in front of a vanity mirror. Wotan, however, head down, occupies a world of his own, busying himself at the keyboard marking Wagner’s score (a common practice throughout this production and at times a bit irritating) completely ignoring his devoted wife and his rather erratic sister-in-law!

Perhaps, Herheim’s making an historical reference here by highlighting the importance of the piano by reflecting upon Wagner’s days of exile living in Zürich. He settled in this German-speaking Swiss canton when fleeing from Germany following his dubious part in the bundled Dresden Uprising of 1848. Furiously working on the Ring, he reputedly gave a concert performance of it in Zürich with just piano accompaniment.

In fact, Herheim elevates the piano to the overall stage action making it the source of the Rhine, the entry not only to Valhalla but also to Nibelheim and everything else in between including the World Ash Tree, Mime’s smithy, Brünnhilde’s rock, Siegfried’s funeral pyre and, indeed, to the score itself.

Interestingly, in Barrie Kosky’s excellent production of “Meistersinger” at Bayreuth in 2017 the Guild of Master Singers arrive by way of a grand piano, in fact a model of Wagner’s Steinway, while the character of Franz Liszt turns up for a guest appearance to play a transcription of one of his son-in-law’s pieces. But no luck this time, I’m afraid.

Overall, a strong and formidable cast was assembled for this cycle that enjoys pace, bounce and consistency. But if there’s anything in opera equivalent to the “Man of the Match” then the person who would get my vote is the German mezzo-soprano Annika Schlicht, reprising the role of Fricka while also taking on the role of Waltraute in “Götterdämmerung.” Harbouring a rich, clear, articulated voice, she delivered a stunning and commanding performance. In fact, one of the best interpretations I’ve ever encountered. Brava!

Hot blooded and on edge, Schlicht’s feisty tête-à-tête with Wotan over the price and terms he bartered with the Giants for building Valhalla was a performance of strength and conviction. With fists flying she laid into him left, right and centre in a bruising and fiery in-your-face confrontation that brought a round of applause from the contingent of refugees. Quietly, I was joining in.

By now they were finding their feet, finding their voice, getting into the stride of their newfound life. In fact, they had now become part of the audience enjoying the ongoing Game of the Gods. They pop up all over the show often bemused by the behaviour (mostly bad!) of the Gods while emphasizing Herheim’s unique setting of the Ring as being a play within a play.

Not only did Herheim direct but he also had a big say in designing the sets working in tandem with Silke Baue. They came up trumps all round with the sets engineered and constructed from old suitcases whilst the employment of heavy-duty silk-like drapes (parachute material?) shaped themselves in a wide variety of configurations over, of course, a multitude of scenes. And to punctuate and identify a particular scene, visual images were flashed on to the drape tastefully created by video designer, Torge Møller, complemented by excellent pinpoint lighting effects conjured up by Ulrich Niepel.

For instance, the dark and forbidden world of Nilbelheim was projected by a fiery red-flame wash as opposed to the brightness and heavenly-inspired white imagery reserved for Valhalla while the rainbow bridge, simplistic in its creation to the nth degree, skillfully used silks to create the peaks of Valhalla while a fusion of colorful lighting and a range of smoke-effect patterns offered Wotan and his godly entourage the perfect (and most romantic) rainbow thoroughfare to paradise!

But if Annika Schlicht put in a stellar performance as Fricka so did Swiss soprano Flurina Stucki, as Freia. Attired in a low-neckline dress over-emphasizing her cleavage to project two large golden balls they well represented the golden apples of keeping the Gods young, healthy and wise! Uta Heiseke certainly came up with the right costume to allow plenty of free movement where it mattered.

No stranger to Wagner, German baritone, Jordan Shanahan, was extremely comfortable and relaxed as Alberich, a role he’s renowned for and interprets so well. After he makes off with the gold, he acts like a bloody madman prancing all over the show brandishing a golden trumpet as if enjoying a night on the town.

His timid-looking and subservient brother, Mime (coming by way of that piano) appears wrapped up in a massive flood of piercing white light and smoke in a fantastically engineered pyrotechnical display. He’s happy as Larry coming into view with the downtrodden Nibelung brigade slaving away at their anvils at thirteen to the dozen fashioning gold trinkets and crafting the most magical helmet of all – the Tarnhelm.

A surefire role, Thomas Blondelle finds good pace as Loge, a gift of a part, though, while American mezzo-soprano Lauren Decker’s reading of Erda was excellent. She sang and acted with such delicacy and truthfulness in a performance of great strength and magnitude. In his arrogant and carefree manner, Wotan didn’t want to know or digest any of her wise words.

The entry of the Giants always offers a great moment to the overall stage action of “Rheingold” especially as to how they represent themselves. In this case, Albert Pesendorfer (Fasolt – later taking on the role of Hagen) and Tobias Kehrer (Fafner – later Hunding) are turned out rugged looking, unkempt and unsavoury (what else!). They are found working alongside a couple of giant carnival-inflated puppets constructed from the odd assortment of suitcases as if jumping from a children’s pop-up book. However, they made a fine deuce while playing their part in Wotan’s Game Show with a touch of panache.

Their hostage Freia found herself dumped in the piano, too, resting on a bed of golden-made objects as part of her ransom dictated by them while Fafner, after killing his brother Fasolt over the argument of his share of the golden bounty, soon takes her place in the piano basking in greed and wallowing in the ill-gotten gains bestowed upon him. Fricka, on the other hand, stands by looking quite forlorn and despairingly over Fasolt’s dead body – wondering! The first manifestation of the curse of the ring as bestowed to the holder by the poisoned, bitter and evil dwarf, Alberich.

As an aside, a couple of characters I always enjoy in “Rheingold” that I associate with the minor roles of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in “Hamlet” are Donner and Froh. Their big moment kicks in at the end of the opera when the Gods are preparing for their heavenly journey to Valhalla. Thomas Lehman as Donner fitted his character the God of thunder to a tee while German tenor Attilio Glaser, portrayed Froh (God of spring) in a most sincere and honest way.

Die Walküre

When the curtain goes up on the first act of “Die Walküre” one’s greeted by Sieglinde, the role so radiantly sung by Norwegian soprano Elisabeth Teige (soon to flourish as Brünnhilde in “Siegfried”) resting in Hunding’s house (on that piano) against a stormy scenario. She welcomes to Hunding’s homestead of misery, motionless and inactivity the weary, burnt out, exhausted traveller, Siegmund, sung by Swedish heldentenor Daniel Frank.

Surprisingly, Herheim conjures up here a fourth character by introducing a mentally-retarded child who, curiously, turns out to be the son of Hunding and Sieglinde. However, the psychological implications surrounding this move completely evades me. Time will tell, I guess, and may even give me the answer.

Acted by Eric Naumann, the Boy’s incessantly crouching and crawling about the place craving for love and attention highly suspicious of the stranger in his midst. Nonetheless, he takes in all that Siegmund has to say when relating his woeful story about his disturbing and emotional past.

And portraying the beastly character of Hunding, the bane of Sieglinde and Sigmund’s life, is German bass Tobias Kehrer, whose strength and accuracy of performance marks his card as a Wagnerian of note. As he steps foot into his house, the atmosphere and tension bites immediately, increasing beyond measure just by his presence.

As Sieglinde relates the story of her forced wedding to Hunding confessing to Siegmund about her unhappy and loveless marriage, the Boy’s annoyingly hopping about round them brandishing a dagger. For what reason? And when she plucks up courage to address Siegmund asking if his father’s name was “Wälse” in a gentle, nervous manner, she immediately recognizes him as her long-lost twin brother.

Another bizarre twist to the overall plot surfaces when Siegmund pulls Nothung from the World Ash Tree while Sieglinde in a wild and desperate state of anxiety grabs the dagger from her son, cuts his throat and covers his body before the deuce come together to deliver that great romantic number comparing their feelings to the marriage of Love and Spring in “Winterstürme wichen dem Wonnemond” pinpointing and summing up their true fate.

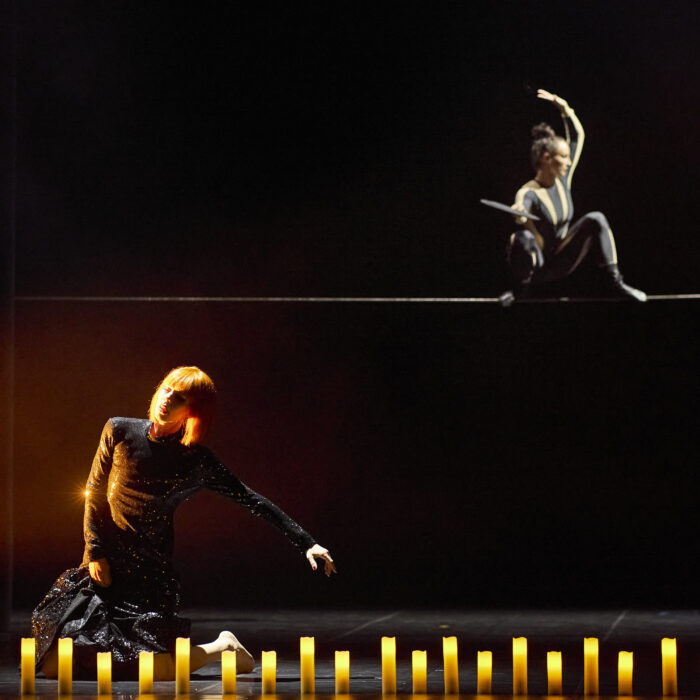

As the scene moves slowly towards its romantic, ecstatic and incestuous end, a striking visual presence of a video incarnation of a wolf’s face is flashed on to the World Ash Tree which dramatically grows out of the piano in which Brünnhilde arises from, too, in a stunning scene in glorious Technicolor ready for her mighty charge in the Ride of the Valkyries which together with the Bridal Chorus from “Lohengrin” is one of Wagner’s best-known pieces.

Standing stiff, upright and proud, she comes dressed in the style of the helmeted British female warrior Britannia protected by her breastplate and shield (ironically, etched with a smiling face) and the silver-tipped spears of her Valkyrie sisters, Wotan’s immortal daughters. Really, Monty Python didn’t seem too far away.

With wild determination, grit and stamina, the role of Brünnhilde was so admirably sung and acted by German soprano Ricarda Merbeth, a superb Wagnerian whose performances I always enjoy. And in this respect, I fondly recall her sensational reading of Senta in Jan Philipp Gloger’s “Der fliegende Holländer” at Bayreuth in 2015. How times flies!

In total control of that famous “Ride,” Brünnhilde rampages and chants her famous battle-cry Hoyotoho! in a well-choreographed sequence performed by an excellent team of Valkyries who found themselves in full flight and in full voice, too, adorned by feathered-winged helmets and other such paraphernalia (they looked good!) with Donald Runnicles in the pit leading his charges to an exciting climatic ending.

But if the Valkyrie’s were found to be in full flight so were the ghosts of the Fallen Heroes surprisingly having the time of their lives pinning the Girls to the floor in a flood of erotic behaviour while similar (and more graphic) sexual antics were seen in abundance in “Rheingold” and “Siegfried” – to the annoyance of many. Shades of David Freeman’s “The Fiery Angel” regularly flashed through my mind.

However, great reverence is shown when Wotan banishes Brünnhilde to her burning rock against a red-draped flaming backdrop conjured up by a brilliant and impressive lighting scenario. As the flames catch hold, the refugee contingent – some now firmly established in their new environment and married with kids in tow therefore forming part of the wider community – form a large circle over a rugged rock-filled landscape (more suitcases!) as if witnessing a ritual sacrifice while gracefully bowing at the exact moment when Wotan abandons her.

As “Walküre” draws to a close, Herheim delivers yet another big surprise showing Sieglinde giving birth to Siegfried while a Wagner lookalike acts as a midwife. Could it be Mime? However, weary and dying, he takes the child from his mother’s arms.

Siegfried

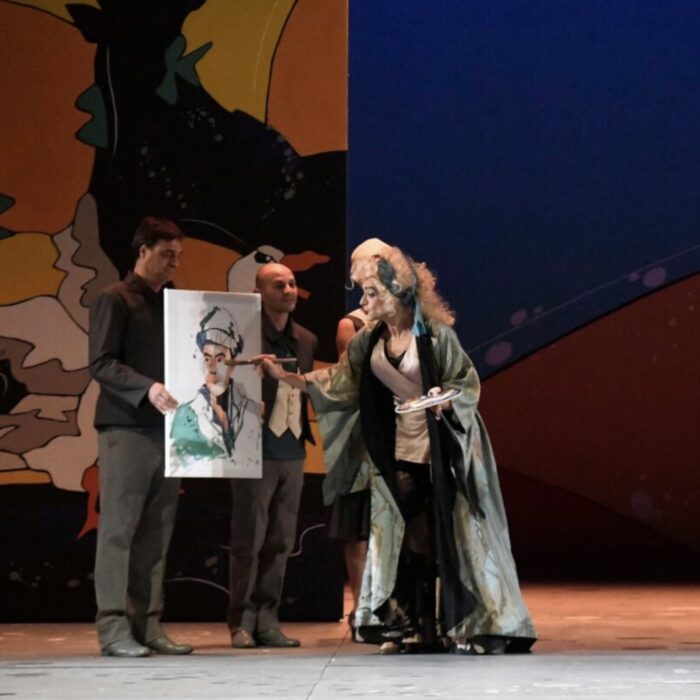

In the first act of “Siegfried,” it’s really Mime’s game. The person taking on this smarmy and unprincipled character, Taiwanise-born tenor Ya-Chung Huang, who studied at the Berlin University of the Arts with Markus Brück and is a member of the ensemble at Deutsche Oper, delivered an excellent account of the role playing the good and faithful parent of the Young Hero in a loving and tender way trying to dupe him, of course, to gain the ring of power.

But the gallant and most formidable role of Siegfried, heroically sung and acted by American heldentenor Clay Hilley, turned the tables on him. With flowing long blonde hair, Hilley looks the radiant all-conquering hero possessing a good stature and roughly dressed as a hunter with a hunting-horn tied to his waist while he acted in that naïve, youthful and uncertain manner that the role demands.

When he took to the slaying of Fafner, I felt the scene had a touch of Broadway fizz about it as the beast was represented by a working team of eight Supernumaries clothed head-to-toe in tight-fitting white costumes each one equipped by a large golden trumpet forming the spine of the dragon. Impressive stuff and visually attractive, too.

The point when Yours Truly overcomes fear and kills the beast, the dragon team break loose gyrating in one big choreographic mess until the bitter end. Tobias Kehrer as the not-long-to-live Fafner knows the game well and played it to his advantage while engaging in some good old-fashioned slapstick with Alberich and Mime for one last time!

However, in keeping with Wagner’s original instructions, Ein Waldvogel was sung by a boy treble in this case Master Paul Kottmann, a member of the Knabenchores der Chorakademie Dortmund. A future Siegfried? He delivered a lovely and tender performance truly capturing the spirit and movement of a bird in full flight.

All change: the role of Erda this time round was admirably and smoothly sung by American mezzo-soprano Lindsay Ammann (American mezzo Lauren Decker took the role in “Rheingold”). And when Wotan interrupts her sleep, he’s wandering and dithering in his crowded and confused mind seeking worldly advice from the one who sees and knows all. But when she denies him her Earth-Mother’s wisdom, he dismisses and consigns her to everlasting sleep putting her below stairs – something that she really wanted, anyway!

An understatement, I know, but the pinnacle to the opera, Brünnhilde’s big awakening number, in which she hails the sun and greets Siegfried as the World’s Light in “Heil dir, Sonne! Heil dir, Licht!” found Elisabeth Teige on terrific form with Clay Hilley, a perfect partner who offers so much energy in performancer. He had to navigate some tricky stage movements, though, to get to her. For instance, he climbs on and off the piano at whim, addresses the refugees, sits down at the keyboard and even has a read-through of his part of the score seated beside Brünnhilde in full voice.

Irritatingly, edging towards the final bars, the stage suddenly becomes dwarfed by copulating couples which, really, I thought was out of kilter and too intrusive to the overall beauty and serenity of such a glorious piece. However, Herheim was generous as regarding their sexual orientation as the orgy depicted boy-upon-boy, girl-upon-girl and mixed company as the case maybe.

Götterdämmerung

The setting for the opening scene of “Götterdämmerung,” incredible as it may seem, was a replica of the main reception area of Deutsche Oper with its massive emblematic cloud sculpture. Therefore, with house lights up the Supernumeraries briefly became part of the audience waiting for the show to begin.

And it begins with the three Norns (Lindsay Ammann, Karis Tucker and Felicia Moore) daughters of Erda gathering beside Brünnhilde’s rock (again that black grand piano) spinning the rope of destiny singing of the past, present and the future recalling the great days of Wotan’s reign while predicting the fall of Valhalla. Cleverly representing the rope were Supers who gracefully moved around the stage in balletic form before the Norns, losing their supernatural powers and their prediction foretold, descend back into Mother-Earth.

Another odd departure from the norm came in the scene when Waltraute comes to warn Brünnhilde to return the ring to the Rhinemaidens to end the dreaded curse. However, she doesn’t gallantly arrive on her steed as stated in the libretto but comes from a seat in the front row of the stalls which, strangely enough, then becomes occupied by Hagen. Another strange quirk of Herheim!

Nonetheless, a beautiful and rewarding scene (one of my favorites!) with Annika Schlicht carrying it off so well, without a hitch, in fact – and with so much dignity and thought to her performance. But Brünnhilde, stubborn and irritated, dismisses her plea. For her the ring is a token of pure love from Siegfried therefore she brushes Waltraute, her favorite Valkyrie, aside, who leaves in utter despair.

Acting strong and forcible in the brutal and bullish role of Hagen found Austrian bass, Albert Pesendorfer, on top form. By now he’s firmly in the director’s chair in the confines of Gibichung Hall exercising controlling behaviour over Gunther and Gutrune, the roles so effectively played by Thomas Lehman and Felicia Moore.

A sort of Bill Sykes’ character, he chills the air just by his presence let alone by his actions conjuring up the evilness that befits a man possessed by greed and envy. At the epicentre of “Götterdämmerung,” he personifies evil touched with a wry and subtle irony but riding for a fall.

And in the final act of “Götterdämmerung,” raging with anger and fury, he decapitates the head of Siegfried whom he had already slain. Siegfried’s funeral pyre then becomes laden with worldly gifts in an act of redemption from the assembled crowd witnessing the execution while a remorseful Gutrune is seen cradling the severed head of Siegfried in her arms echoing Salome’s erotic dance round the decapitated head of John the Baptist.

Proving her worth as a great Wagnerian, Ricarda Merbeth as Brünnhilde sang the part in a grand and flowing Wagnerian style delivering a joyous and masterful performance which manifests itself in the brilliant finale in “Götterdämmerung,” the well-loved Immolation scene. It’s at this pertinent point that Brünnhilde realises the consequences of lust, greed, corruption, that lie at the very heart of the Ring, is completely and utterly worthless.

As Siegfried’s funeral pyre is set alight simple but effective staging kicks in with the Supers seemingly on fire, too, with their arms at full stretch collectively acting as the flames while circling the funeral pyre before it makes its journey down the Rhine.

The End Game of the Gods and a new dawn beckons with Deutsche Oper’s house cleaner walking across a bare stage save for that black grand piano still stuck in the middle clearing up a god-awful unholy mess!

At curtain call the audience erupted with wild applause but when Deutsche Oper’s general music director, Scottish conductor, Donald Runnicles, whom I rate as one of the finest Wagnerians around today, took to the stage along with all the members of the Das Orchester der Deutschen Oper Berlin, the audience erupted even more emphasizing that the work done in the pit equals to the work done on the stage. It was standing room only. Deservedly so!

Moving on! Maestro Runnicles, 68, who has led Deutsche Oper Berlin since 2009, leaves his post in 2026, a year earlier than his contract states. After welcoming Deutsche Oper’s new Intendant, Aviel Cahn, 48, currently general manager of the Grand Théâtre de Genève, succeeding Dietmar Schwarz, Runnicles jets off to the US where he’s music director of the Grand Teton Music Festival in Jackson, Wyoming. He has extended his contract there to 2029 and, therefore, will notch up 23 years with this distinguished festival. Bravo!

Ring extra! The Ring fitted Wagner’s mood and personality like a glove. His ideas were always adventurous and larger than life and in a matter-of-fact sort of way he specifically knew how he wanted his productions to shape up. In recent years Ring directors have been just as adventurous but their productions have been light years away from Wagner’s original intentions to the annoyance of the Wagner Traditionalist Brigade!

However, I remind myself of George Bernard Shaw’s waspish remarks saying that the best way to enjoy the Ring was to relax at the back of the theatre with your feet up, eyes closed and just listen to the music. He was just as cantankerous as the Wagnerian old guard is today. But give it a thought. Just think of what you would miss.

However, I think it’s fair to say that Herheim’s realization of the Ring keeps the work firmly on track with forward-thinking audiences. Like any director, he harbors strict and definite ideas on how he wants his Ring to shape up – some you got, some you didn’t, but it was that sort of production but a production that made you think.

I have a shrewd idea that Herheim’s Ring (which he has most definitely reshaped for the 21st century) will endure a good innings just like Götz Friedrich’s production thoroughly enjoyed.