Deutsche Oper Berlin 2023-24 Review: Das Rheingold

By Vincent Lombardo(Fotos von Bernd Uhlig, Kontakt: bernd.uhlig.fotografie@t-online.de)

It does seem that the 2021 Deutsche Oper Berlin’s Ring has been somewhat of a success over the last few years. And this is good for opera. A major achievement, this as other cycles, after the centennial Patrice Chéreau staging have created negative stirrings, indeed vivid contestations largely due to mistaken stage-director conceptions ingrained at the outset and proving irremediable over the arduous course of four evenings. Some versions were so intellectually complicated that the audience lost track of the plot, if not having saved themselves by resorting to the director’s QR guide beforehand for partial illumination, and often abandoned partaking in the theatrical ceremony that is the Nibelungen’s saga (Wagner’s stage–festival-play), closing eyes to the debacle in choosing to “listen” to the music alone… truly a defeatist solution.

This recent creation by Stefan Herheim and Sir Donald Runnicles may appear as one of the most enjoyable to be sure; a lively-paced, imaginative “kermesse” capturing our senses, though sadly at times offering so much in excess, mostly mimetic stage action, that we lose contact with the structure of the tightly knit drama.

Das Rheingold

The first scene of “Das Rheingold” does bring us face to face with the beauty and weaknesses of this production. Its merits are that it is hardly ever inconsistent once a character or scenic element is decided upon, yet it is to determine whether that choice interferes with Wagner’s intentions by transforming and transferring all, save for the music, into a different realm. Deutsche Oper’s “Der Ring” amuses, swirls, makes sense upon its own terms, but sadly creates another theatrical reality. One major offense, though admissible, is cancelling the performance distance of the “mystic gulf,” that innovative space between public and stage action that Wagner envisioned within the confines of the Bayreuther Festspielhaus, itself wisely left untouched since its 1876 unveiling. No slight variation, then, this “breach” of Wagner’s spatial creed which occurs not only in the first episode ‘beneath’ the Rhine, but is again applied in an ever more Brechtian way in “Götterdämmerung,” as we shall see.

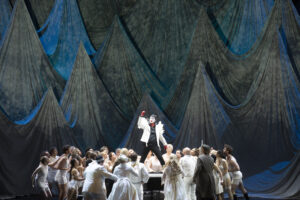

Though risky as almost always today for stage directors to incorporate their own personal, however removed “pantomimes” as stage action during Wagner’s musical Overtures, Prologues, Preludes, all in the name of Zeitgeist, Herheim’s beginning creates an interesting image – refugees entering upon the empty stage where the entire action of “Der Ring” will take place. A farraginous group of forty “wanderers” led by Wotan appear before us. The last traveller has a trumpet dangling from one hand, and we may sense that this is the coveted “gold of the Rhin.” Upon a grand piano sitting on one side of the stage, Wotan strikes the ominous, other-worldly note that opens the whole cycle – and here Wagner makes his entrance in spirit. But it is Wotan, in wonder, who breaks through the “fourth wall” looking out to us, the audience. All the wanderers do the same, and we exist for them. But why must we? Is this a hint of a “popular” Ring? Are we now, as under the spell of Andy Warhol’s 1968 edict on “fame,” all of us becoming universal protagonists, images, for 15 minutes, only then to disappear? Here, we also look at those who have invaded “Das Rheingold,” scrutinizing them as they do us. The costumes are cleverly interesting as they delicately hint to East Europe, but in detail reveal bohemian personalities, perhaps poets, dancers, actors, journalists, all told, then, intellectuals, as each one has a touch of the individual.

The prologue begins, at first whimsical, with the effect of a Broadway musical. Wotan, Alberich and the Rhine Maidens are mixed among the “immigrants” upon the stage, soon to become, as was Wagner, “in a somnambulistic state, wherein (one) had the sudden feeling of being immersed in rapidly flowing water.” Yet, all soon reveals itself as over-abundant. With suitcases down, the wanderers follow Alberich as he sings his first words, reacting to each other in whispers as all opera choruses do in crowd scenes. They do their best, but we do not believe them, as acting for this sort can never be credible. We take note of Wellgunde, who after having humiliated Alberich by pulling down his pants and mocking his prowess, is embraced by a gym-fit model, a “Ken” of Barbie fame. Alberich will shortly challenge him in jealousy but is forcefully pushed back. Recall that only minutes ago, this Mr. Ken was in search of a homeland. Now Flosshilde, through her lull-a-bye tune, gives Alberich hope; she might be the one he can conquer. All becomes erotically charged. The wanderers undress each other down to their underwear (which they will do in other scenes throughout the cycle). Then, magically, all this hubbub finishes as shimmering violins bring us the motif of the Gold itself. Alberich grabs his trumpet, holding it out solemnly as Parsifal would the Gral chalice. Wagner’s leitmotif hypnotizes us all, and the world stops as it should. The sun penetrates the depths of the Rhine, or is it also true, our depths? A French horn chorale reminiscent of “Die Freischütz” depicts the warm miracle of approaching day.

From the piano, comes the first of many objects and persons. White silk sheets are pulled around by the wanderers, forming a circle about the Rhine Maidens, shimmering white and gold. All stops dramatically as Woglinde echoes their father’s soul-shaking warning that possessing the gold implies a denial of the presence of love in one’s life. But, as Wellgunde tells us, we are safe from this danger as we are all full of love in our lives, and everyone on stage wrapped in the white silk sheet begins to touch each other in erotic ritual. In a tableaux vivant pose, the trumpet becomes their Golden Calf. But then, Alberich decides against love, and the will to embrace others. He chooses wealth, power. In a phrase that perhaps often goes unobserved, he admits that true love cannot be forced upon anyone, and declares that he will attain love through cunning, be this today’s unromantic love. In all, this made sense, if not illustrating and representing the text in an obvious manner. Today, one may truly enjoy the visuality of the goings on, and even seasoned Wagnerians may accept this treatment. And life continues … but have we been given too much? Has all this been done for us? Wouldn’t it have been enough to enact Wagner’s vision of Alberich’s frustration amply shown on stage by having him slip upon the unsure footing of the Rhine’s algae bottom, unable to grab, then keep hold of a pretty maiden? Or has all this stage action, though amusing us, rendered him less sad, selfish, pathetic? In a smattering of dialogue between the dwarf and the saucy mermaids, wherein in effect Wagner dissects the mechanisms of the ‘flirting’ game, we must by now accept Herheim’s Alberich as resembling “The Joker,” a bad man on the way to perhaps becoming an anti-hero, a personification of the irrational.

The next three scenes of this vorabend bring us face to face to the characters who shape the story of their desires to possess the ill-forged ring itself. These weavers of timeless illusions allow us to discover our human weaknesses through falling prey to power and worldly gain, accumulating guilt along the way. All begins according to Schopenhauer’s warning that Man knows he is immortal and will thus seek power on Earth in order to put off this destiny. But with power, we also must deal with deceit, corruption, and must live by the sword, so to say, renouncing love (human values, in the strict sense of the word), and by so doing, putting into action our own end. This is the essential tragedy of Wotan, who here set all in motion by striking that first note on the keyboard; it is his fault.

So much goes on scenically that the giant fable is brought front and center, where much is over-explained, making this in some ways a perfect introductory “Ring” for novices and children. Perhaps, only the experienced Wagnerian will differentiate between what is Wagner or not as to the character’s motivations, what is of worth in an illuminating way, and what is not. We quickly note that the Rhine Maidens do not float away into the depths after the gold is robbed but remain on stage among the wanderers for just about the entire opera. Upon awakening in Scene two, Wotan’s pride leads him to musically conduct the “Valhalla” theme before the wanderers, who applaud him, but only after his prompt. Here we have it: we have seen Wotan before, we know him somewhat, but now his many idiosyncrasies befuddle us, and we ask if what we are learning of him makes him all too accessible, and perhaps less interesting. His wife Fricka also over-indulges in gesturing, yet, as true to Norse mythology, she begins her licentious flirting with just about anyone. Human, all-too-human.

A versatile “stage,” characterized by much movement around a grand piano center stage – a magical instrument from which characters and objects arrive. Herheim will fill this fairy tale landscape with child-like inventiveness, yet failing at times to convince us or create wonder. Multitudes of piles of the wanderers’ suitcases form the caves of Nibelheim, and to great effect. We will come to know that according to the theatrical lighting shed upon them in the other operas, these symbols of salvation, of hope will assume a majestic, yet also threatening nature. In fact, the giants Fasolt and Fafner, though stage presences, are portrayed by two huge faces made of suitcases, puppet-like in moving their lips to speak, foreboding. As marionettes, this is a deft touch, yet perhaps pushing the suitcase symbolism a bit too far, losing effect while also dwarfing the Giants on stage.

Odd episodes create perplexity. Wotan, in pulling the ring off Alberich’s finger, also pulls his finger off. He removes the ring, and throws the finger to Loge, who clumsily disposes of it. Alberich, when at first captured and transformed into a toad, here frees himself momentarily; moments late, Mime, seated at his anvil, rises from within the pianoforte, and bangs Alberich on the head, knocking him out. This to the metallic clangs of the miner slave workers marching out as helmeted German WW2 soldiers. Shtick is shtick, but one remains perplexed. At any rate, this orchestral interlude now assumes another sense, but not as set out by Wagner. Additionally, the score of “Das Rheingold” becomes a stage prop used excessively (we already have the grand piano in view); various characters possess it, sing from it, bang it. At the end of the “Magic Fire” music, Wotan puts it down, punches it, mimes that his hand had penetrated it – and voilà! He non-magically pulls the sword Nothung from it and plunges it not into the great oak tree but into the piano’s keyboard. Again, there may be meaning if one wishes, but its all superfluous … stage action for the sake of stage action.

And then, a grand return to Opera: the scene that heralds the arrival of Erda is wonderfully staged, her gestures shaping the music. Though her arrival, walking up the steps from the downstage prompter’s box, is neither magical nor telling of her essence, Herheim gives her free roam to exert her powers upon an undisciplined Wotan. In fact, her costume seems to be that of a modern-day school mistress, thus a symbol of her fountain of wisdom as giving nutrition to the World’s Ash Tree, offering shade and comfort to all, its branches even touching the heavens. Removing her eyeglasses, she delivers her cryptic message, perhaps a mysterious Rune poem, and as is understood by Wotan, who yields to her power. She embraces herself matronly but does not allow Wotan to touch her. Only when she picks up the score do we finally sense the eternal outpouring of Wagner upon the pages, which she holds protectively. Her earthiness is in her wisdom, the power to see truth as the only salvation we have, and her words come not deeply from the earth, but from the soul of our better sense. Her glances look not outwards, but within.

The wanderers are dragged into it all, and thus lose their effect as true immigrants breaching Wagner’s world. To state, some of the most beautiful moments are created throughout this “Der Ring” when they, as a passing flock stop, observe, yearning to participate in the stage action, to understand, to empathize with the uncomfortable, irresolute situations of, say, Brünnhilde, Wotan, Sieglinde. Here, they reflect us, the audience, and are felt moving in their silence and steadfastness of intent upon the dramatic action. One feels sad for them as they remain outside the action, yet warmth, for their humanity in wishing to participate. Their immobility, steadfastness even, seems to bring all to a standstill, and the meaning of a

dramatic moment shows another face, where no words, no action are needed. The deepest sensation is called “truth” – here music alone illuminates us.

The ending of “Das Rheingold” comes upon us quickly, and we are aware of Wagner’s music growing in tension, swelling. The Gods huddle about the piano, as if all were a Liederabend : Froh plays, Wotan in the soloist singer’s stance, Fricka and Donner joyous in song, while Freia remains on the floor near the fallen Fasolt, lamenting his death. Loge is distant, leaning against a side wall, thinking how foolish they all are in deluding themselves. Compelling are his words: “They are hastening to their end, though they think themselves strong and enduring.” The entrance of the Gods into Valhalla is of ephemeral joy Loge tells us. As Freia and Donner disappear into the depths of the piano, the wanderers pack their bags and return along with the Rhine Maidens lamenting their loss of the Gold. Wotan forces Loge to accompany them on the piano. In a way, it is sad that there is no distance between them and the Rhine Maidens, who should be calling from the depths; their interchange with Loge has much less effect here as they proclaim that “tenderness and truth” reigns below, while a new world order above has been set into motion by those “false” and “immoral.” The distant wailing of the innocent bereft of its natural treasure is moving; Nature has been violated, and it was so through its contact with humanity: The pure and blessed are unaware of Man’s willingness to destroy, to acquire lustfulness and longevity through power. The Rhine Maidens pull

an enormous silk sheet from the piano, which flown upwards takes the form of the tree we will see in “Die Walküre.” All flee the stage, and there within the tree, an image of the “embryo” of Siegmund e Sieglinde appears. It is Wotan, the last to move, as he disappears down though the prompter’s box towards Erda, perhaps to finish the discourse by her prohibited. All given, the impressive goings were visually invigorating, yet tinged with scenic déjà vu. It was the music that dominated the scene.

Musical & Production Highlights

Much credit must be give to the conducting of Sir Donald Runnicles, the original Maestro of the 2021 premier production. One has the impression that the tempi were quite evenly dispersed, if not seemingly a bit sprightly. Though the two-and-a-half-hour span is quite common, basically only Karl Böhm (2:16) and Pierre Boulez (2:22) are quicker, with Simon Rattle live at the 58th Aix-en-Provence Festival as the slowest (2:45). Perhaps the reading of Runnicles with the Deutsche Opera Orchestra playing lightly, to say, ensemble orientated. It resembles Marek Janowski’s studio Das Rheingold (2:18) with the

Dresden; intimist, chamber-like in that the spoken-sung text captures our attention, moment for moment, as if in classical theatre.

The singers were commendable, a uniform element that earnestly carried the dramatic events nobly. Iain Paterson’s Wotan explored the complexities of a God continually under pressure, thus requiring an ever-changing mobility, a shiftiness and falsity like Don Giovanni. He explored the vocal range of Wotan’s expressiveness.

Donner (Thomas Lehman) and Froh (Attilio Glaser) were the spunky Gods of Thunder and Sun, nimble in serving, putting on display their powers in ironic, zany manner at times.

Alberich (Jordan Shanahan) was asked to be ever active, intermingling not only with the Rhine Maidens, but also the troupe of wanderers; his interpretation of the music evidenced great range of timbre, perhaps underlying his struggles of being accepted for what he is not.

Mime (Ya-Chung Huang) was a most convincing half-brother to Alberich, and dressed as Wagner was a dutiful artisan, also animated at the pianoforte. The voice is rich, challenging all the nuances of the role.

The giants Fasolt (Albert Pesendorfer) and Fafner (Tobias Kehrer) were cast into minor light here; of normal height once detached

from the suspended suitcases forming their faces. Their singing was most interpretive, they displaying the weaknesses of human fragilities, as hinted at by their yippie frockcoats: Fafner obsessively falling in love with Freia, and Fafner, rotten inside, scheming to possess the Gold and the power it will bring him.

Fricka(Annika Schlicht) possessed an extraordinary voice, displaying a vocal range of sheer power, yet used with subtlety.

Freia (Flurina Stucki), her breasts as golden apples, was all the victim of Wotan’s corrupt dealings, and portrayed her music with the needed sense of desperateness, as with the tenderness necessary when lamenting Fasolt’s death.

The Rhine Maidens did more than necessary and were on stage in continuation. Vocally homogeneous, they conveyed their innocence, yet also their interchanges as sisters.

Credit must also be given to the Costumer, Uta Heiseke: All is handled with suave dexterity, adding to the characters personalities – restrained blue-greys and browns sustaining the role of the wanderers as observers-protagonists. Loge is a squeamishly squirmish, a Mighty Mouse in red and black, launching flames upon others’ sleeves, shoes, or hair, and is often miming the fiddler, showing off as to set the rhythm for the orchestra as everyone else but Wotan, frozen in a tableaux vivant ; Loge appears here as the devil from Stravinsky’s “Histoire du soldat.” The giants Fafner and Fasolt as dressed seem to be friendly State officials in their Victorian frock coats of outlandish colors, and as such, seem to have done all the contractual paperwork regarding their construction of the castle Valhalla, missing only are those rolled up architect designs. Froh is dressed in white, pirouetting as propelled by tiny angel wings, while Donner carries pistols as well as his hammer to strike thunder. Though to say, even in this production, Wotan, soon the Wanderer, will be condemned to wear that stereotyped long, double-breasted Victorian topcoat, so often seen in many Caspar David Friedrich paintings.