Deutsche Oper Berlin 2019-20 Review: Heart Chamber

Chaya Czernowin’s Thrilling Work Undercut By Vibrant But Questionable Klaus Guth Production

By Elyse LyonThis review is for the performance on Nov. 15 and 21, 2019.

A common complaint of the current age is that, despite our cell phones and social media profiles, humanity is lonelier and less connected than ever before. Newspapers warn of a “loneliness epidemic,” think pieces term it a “social cancer,” and streams of articles comment on topics such as Britain’s appointment of its first official Minister for Loneliness.

Chaya Czernowin’s “Heart Chamber,” in its world premiere at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, was clearly a product of this age. Often, it seemed a response to the similarly timely issues surrounding the #MeToo movement, with its explorations of gender dynamics and its allusions to the dangers inherent in intimate relationships. Ultimately, however, it seemed above all an examination of loneliness, its score and libretto working together to depict and analyze isolation and its causes and effects.

Loneliness Through the Guth Lens

In its staging by Claus Guth, the curtain rose on the work’s two protagonists, characters listed in the program under the names of “She” (Patrizia Ciofi) and “He” (Dietrich Henschel). The two figures sat rigidly on a black stage, each marooned in an island of stark, chill spotlight-glare. They were separate from each other, inert, initially silent and seemingly lifeless.

Aside from the chorus, which was physically separated from the stage—two groups of eight singers each, ensconced in boxes ordinarily occupied by audience members—the cast list featured few other singers. The “internal voices” of She and He were performed by Noa Frenkel and Terry Wey, respectively, whereas a figure called “The Voice” was depicted by Frauke Aulbert.

All the singers were amplified: a necessity for Czernowin’s composition, which utilized not operatic styles of singing, but rather whispers and hushed words and quiet vocalizations. The amplification, intentionally or not, made it difficult to distinguish between the characters and their internal voices, due to the fact that the audio emerged from the same speakers and the vocal scoring did not allow one to easily pick out one voice from the other.

The internal voices, when they appeared, were clothed in dark, unobtrusive garments, and unless one were studying the movements of their mouths, it was easy to miss that they sang at all. The effect was to further concentrate attention on Ciofi’s She and Henschel’s He, further increasing the impression that those characters existed in a solitary void.

Modern & Timeless

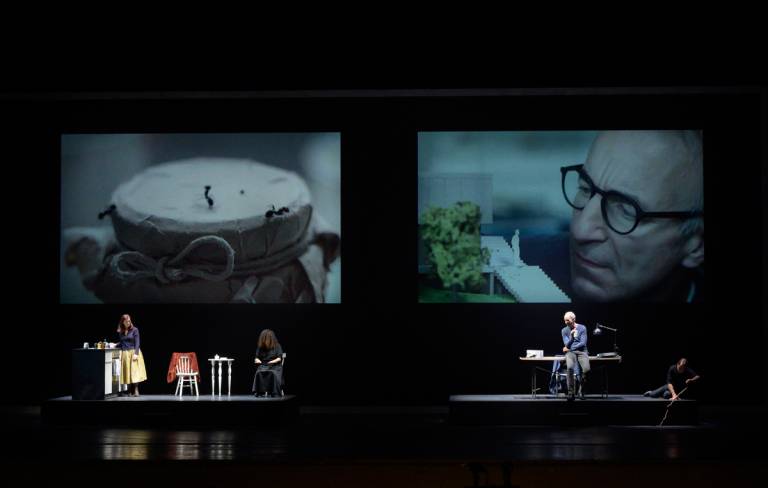

Guth’s production was a cinematic one. Well before the first line of the libretto was voiced, video projections blinked into life above the characters’ heads. While She and He remained marooned in their circles of light, stone-faced and motionless as marionettes with their strings cut, the videos above their heads showed them moving through a city.

This city was recognizable as Berlin. The time was recognizable as the immediate present: one of the fleets of e-scooters recently and contentiously introduced to Berlin was prominent in the foreground of one shot.

Even so, the videos appeared to have been designed with an eye to generality as well as specificity. No Berlin landmarks appeared in the shots. Despite the undeniably present-day e-scooter, the cinematography (often in black and white) evoked street scenes of many decades past. It seemed to hint that the issues at play were simultaneously local and general, simultaneously modern and timeless.

As the work progressed, such a treatment appeared increasingly apt.

“Heart Chamber” spoke directly from the contemporary zeitgeist—our concerns with loneliness, mental health, toxic relationships between men and women—but none of the issues it addressed were exclusively modern. Though the scoring was entirely contemporary, with its amplification and its unconventional use of singers and instruments, only a few words in the libretto located the work in a specific time or place.

A single mention of a telephone, for instance, was all that indicated an indisputably modern setting. The overwhelming emphasis was on the human soul stripped bare: a nameless pair of human beings, naked of all determiners aside from their genders and their longings and their pain.

(Credit: Michael Trippel)

Psychological Nudity

Guth’s staging, in his strikingly beautiful and incisive production, supplied the outward context of She and He. In his projected videos, they strode the streets of the city, appearing wealthy, confident, beautiful. They were, in Guth’s rendering, the kind of people one admires and envies: the kind of accomplished city-dwellers whose clean white houses are featured in architectural magazines, and whose lives seem focused, ascetic, and flawless.

Czernowin’s score, by contrast, told the opposite story. The work, from beginning to end, conveyed the experiences of panic and extreme isolation. The sounds that filled the auditorium resembled, by turns, the sounds of one’s own body, the anonymous noise of the city, and the distorted perceptions of a person in extraordinary mental distress: amplified breaths, ominous thuds, the strange quiet noise of the brass players breathing through their instruments rather than playing them in the traditional manner.

Ciofi’s She, throughout, was clearly the center of the emotional narrative. She sang and whispered her lines in an English that was often heavily accented. The libretto itself, as printed in the program, gave no indication that the character of She ought to be portrayed with an accent, but Ciofi’s portrayal of She as a non-native English speaker came off as deliberate, insightful, even crucial to understanding the work.

Czernowin, as the work’s composer, is no stranger to foreignness: born and educated in Israel, her adult career has played out in Asia, Europe, and America. It was hard not to feel, watching the production, that the work was an act of psychological self-revealing.

The scoring strongly evoked the experience of being an outsider in a strange city or country: a place where one seems worldly and accomplished from the outside, striding through city streets that people from home can only imagine—and meanwhile, despite outward appearances, one feels the terrifying solitude of the foreigner.

Those who have been alone in a foreign place might well shudder in recognition at the auditory environment Czernowin’s score created. It was the music of isolation, in which the inhuman sounds of the surrounding world swell in one’s ears until they become overwhelming. Stripped of family and friends and community, one hears the entire world differently. Breaths; the clatter of rain; the rasping, plinking, shrieking and thudding life of a city: these sounds are unremarkable to a person immersed in local life.

To an isolated newcomer, however, such noises are often one’s sole companions: the soundtrack of a life barren of familiar sounds and friendly voices. Czernowin’s scoring seemed to reflect such lonely experience, and to make excellent use of the auditory sensitivity that a person gains through such isolation.

The narrative of the work, as well, spoke to isolation. The story was simple: She and He met by chance, dreamed of a happy life together, but ultimately failed to surmount their own fears and emotional burdens.

It was a deliberately ordinary story, deliberate enough to seem almost cliché. There was truth in it, though, of a kind that rarely appears on opera stages: neither triumph nor dramatic tragedy, but merely the stuff of sad ordinary lives. Two people met in passing; they were lonely enough that their chance meeting seemed something extraordinary; they dreamed of happiness and children, but instead they fought and parted.

Their obsession with each other was the needy longing of extreme loneliness. One moment they were strangers; then they were wary of each other, afraid of trusting too much. Then, all at once, they were simultaneously obsessive and fearful: “Will you wrap me with your flesh? Will you never leave me?” they begged one another. Pained, vulnerable, anguished, requiring more of each other than any mortal could give: “Will you be like a father, but a good father? Will you care for me like a mother? But do not die?”

The words of the libretto, all the while, stretched out and distorted themselves. Often they resembled the sensations of an extended panic attack, during which time slows to an agonizing crawl and words seem to echo and drag through interminable empty corridors before finally reaching one’s ears.

(Credit: Michael Trippel)

Troubling Questions

It remained difficult, nevertheless, to evaluate “Heart Chamber” in the context of opera. The work is not strictly an opera—“music theater,” the program termed it—and its amplified voices and instruments, its half-spoken lines and magnified breathing, were as much akin to theater and performance art as to the tradition of classical music.

It was intriguing to see such a work on the stage of the Deutsche Oper, with the questions it raised about what belongs on an operatic stage. On one hand, Czernowin’s work was invigorating and refreshing, with its contemporary sensibility and its experimental use of instruments and voices.

On the other hand, however, the Deutsche Oper’s choices raised more troubling questions. Many audience members commended—rightly so—the Deutsche Oper’s decision to promote a female composer. Such promotion is depressingly rare, even in such a forward-thinking musical environment as Berlin’s.

There was something dismal, however, in the Deutsche Oper’s presentation of the work: though Guth’s production was gorgeous and incisive, though Johannes Kalitzke conducted the complex score capably, it was somewhat disheartening to see Czernowin’s work in their hands.

While Berlin’s Staatsoper falls short in featuring female composers, one often sees conductors and directors there who are young, female, or (occasionally) both.

Berlin’s Komische Oper likewise falls short in terms of female composers, but abounds in youthful, unconventional energy. While the Komische Oper has made a point of seeking to connect with Berlin’s Turkish minority, the Staatsoper, with Daniel Barenboim as its musical director, has close connections with the Barenboim-Said Akademie and the range of often highly political events presented at the Boulez Saal. Four days after the premiere of “Heart Chamber,” for instance, the Boulez Saal featured a lecture on the marginalization of Black feminists, directly followed by a poetry reading by non-European writers entitled “A Woman’s Voice is a Revolution.” The Staatsoper’s audience might not have flocked to such lectures, but the same event included performances by Barenboim, Michael Volle, Waltraud Meier, and Dorothea Röschmann. The printed program covered all related events, so any audience member who came for the music would be treated to a program featuring heated interviews on war, racism, activism, and oppression.

The Deutsche Oper, by comparison, often seems depressingly risk-averse even in its most avant-garde productions. How risky is it, after all, to present a serious-minded work composed by a Harvard professor in a production by a director as esteemed as Claus Guth? The choice seemed almost backward-thinking: an embrace of academic accolades, of white-haired conductors and eminent male directors. One wondered, at “Heart Chamber,” whether the Deutsche Oper was merely checking off boxes, reaping the reputational rewards of being so open-minded as to feature a female composer while simultaneously entrenching itself in popular repertoire overwhelmingly conducted, directed, and composed by men of European ancestry. One does not want an opera house to arrange its season solely based on ethnicity or gender. One does, however, want to feel as if an opera house truly believes in the vision it states.

The inclusion of Czernowin’s work in the program was unconvincing: conducted and directed by eminent men, its premiere slotted between “Nutcracker” and “Tosca,” it came off as an event one was meant to attend out of duty, as if the bitter pill of an avant-garde female composer’s work had to be sweetened by the comforting familiarity of Claus Guth’s name on the program.

This, of course, serves no one. Though the composition was intriguing and the production engrossing, the overall effect was depressingly joyless. Guth’s production, brilliant as it was, was the product of a well-known entity. The premiere, therefore, lacked a sense of genuine risk and discovery.

One wished for a treatment of the work that pushed the boundaries of opera further. A less eminent and accomplished director might (or might not) have produced a less polished production, but a more experimental and risk-embracing production might well have imbued the night with real excitement.

As it stood, the premiere fell flatter than it should have: forward-thinking on the surface, conservative beneath, it neither pleased audience members with traditional tastes nor thrilled those with an appetite for experimentation. Guth’s production was a good one, and it must have cost wads of money, but nevertheless it seemed to do Czernowin’s work an injustice. A thoroughly risk-taking production might have made it an evening to remember; instead, it came off as a promising work presented in a beautiful, expensive, but unexciting manner.