Detroit Opera 2022-23 Review: The Valkyries

Wendy Bryn Harmer Shines in Experimental Production of Wagner Classic

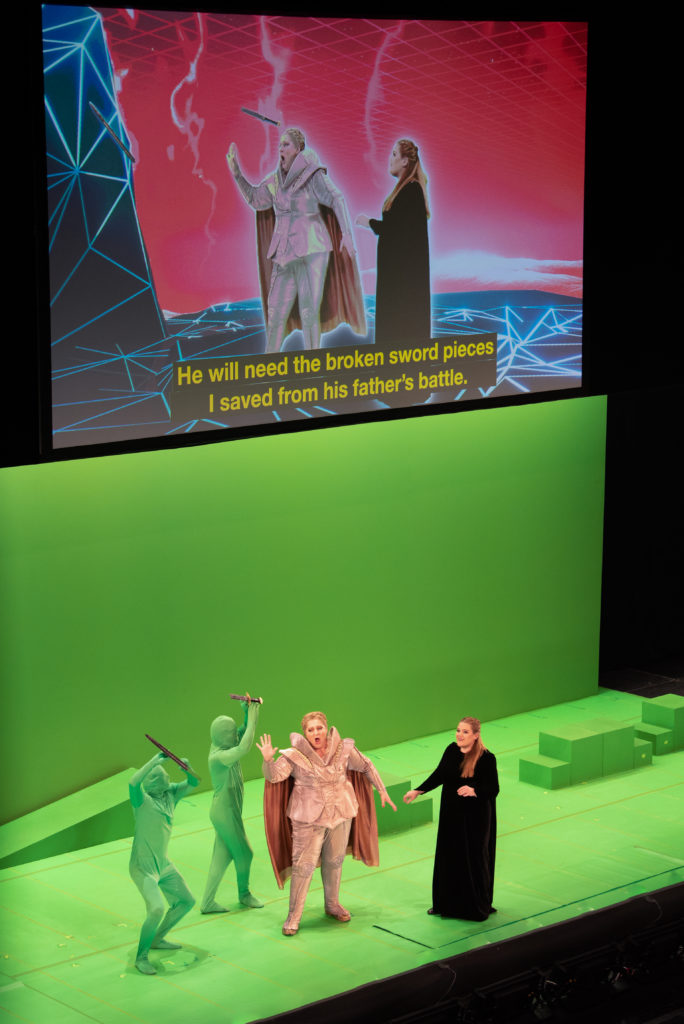

By John VandevertOn September 17, 2022, the newly renamed Detroit Opera, formerly Michigan Opera Theatre, mounted the first production of their 2022-2023 season. What Detroit Opera (DO) presented was nothing short of unique. Marketed as a “one-night miracle” by the Los Angeles Times, DO’s digitally enhanced retelling of Act three of Wagner’s “The Valkyries,” the second in his four-opera epic “The Ring of the Nibelung,” was a valiant attempt to revolutionize operatic theatre by exploiting the technological capabilities of virtual-reality (a sexy, new 21st-century fad).

Israeli-American Director Yuval Sharon strove to reflect, in his words, the “curiosity and caution as to where the art form of opera might be headed” by fusing real-time graphics and three-dimensional, animated topographical atmospheres with traditional Wagnerian musical dramaturgy.

While the green-screen effects with top-notch singing were visually lukewarm, musically, DO’s innovative experiment was truly exceptional. As baseball fans roared at the nearby stadium and hordes of city-dwellers partied outside, inside the Detroit Opera House, an awe-inspiring achievement for opera was happening on an international scale. While not the first company to blend virtual reality with opera (Irish National Opera’s Out of the Ordinary by Finola Merivale and Jody O’Neill also uses such a pairing), DO’s collaboration with PXT Studio and Detroit College for Creative Studies was nothing short of amazing for what it was—and that was art.

Art in the Wagnerian conception is truly a modernized variation of Gesamtkunstwerk that Wagner himself would have exploited if given the chance. Yes, there was the occasional green-screen malfunction, iffy costume choices, and less-than-stellar vocal moments (Even Wotan has off-nights), but in the end, who cares?

In the larger picture, what DO accomplished proved that opera isn’t a dead art form. If anything, opera is more alive than it’s ever been, and now that podcasts and YouTube operas are things, the sky is the limit in terms of opera’s development.

Stepping into one of her many signature roles as Brünnhilde, the brilliant dramaturge and vocalist Christine Goerke was joined by an equally successful cast of veterans and young artists. These included internationally recognized bass-baritone Alan Held (Wotan), the critically acclaimed mezzo-soprano Wendy Bryn Harmer (Sieglinde), and a sensational cast of eight sisters, each one an obvious master of their craft. The orchestra was led by English conductor Sir Andrew Davis who, in 2005, conducted his first Ring Cycle.

So, it wasn’t too surprising that he pulled from the pit Bayreuthian magic, full of the sumptuous gravitas that Wagnerian music rightly deserves and which many a conductor to this day struggles to nail, much less embody, as a way of being. I would be remiss if I didn’t draw attention to the people behind the curtain, as the creative nine-person team, alongside the four-person stagehand crew, not only excelled but kept the show together. DO has always been an opera house known for its first-rate teamwork, and it was on full display. Every person knew their duty and executed it with gumption.

Sharon’s Vision

Sharon notes that the aesthetics of DO’s virtual-reality mediated opera was inspired by Steven Lisberger’s Tron, a story about an eminent computer programmer and video game developer’s harrowing journey from a VR landscape known as “The Grid.” Critics praised the original 1982 film for its ingenious and ahead-of-its-time computer-generated imagery (colloquially known as CGI) and visual language.

The film’s soundtrack was composed by the equally seminal electronic-music composer Wendy Carlos, best known for her “Switched on Bach” album released in 1968, establishing herself as a groundbreaking and historic leader in the field. Sharon also used the 80s and 90s “Vaporwave” aesthetic, a retro-futuristic musical and aesthetic micro-genre that plays on a nostalgic pull for fictional post-human realities. Vaporwave relies visually on dated Internet spaces and cyber imagery by collating cyberpunk elements like rotting dystopias with the sexual allure of the neon metropolis, complete with ‘glitch art” (i.e., corrupted digital effects), anime, 3D objects, and spaces. Neo-Grecian imagery and Hellenic symmetry a la 17th-18th century Classicism are also part of the mix.

A hallmark of the Vaporwave style is the coterminous relation between the safety of the familiar and the trepidation of the surreal. It’s a dance between the known and unknown through the coaxing use of grids and “Star Trek” “Hollowdeck” gridding with faded hues against high-res colors. Designed to be a sardonic critique against homogeneous corporatism and the hollowness of modern life, Sharon’s usage of this aesthetic language for his production is a masterful and necessary prophylactic against the mindless adherence to tradition and the standard conventions of our antiquarian past.

Wagner adaptations always make people come out of the woodwork, but in Sharon’s case, it worked. That being said, the three-screen setup was excessive, and the stark treatment of the stage (done so in order to accommodate the five camera posts which fed footage to the screens) did not convey, at least properly, the intended message.

As the director notes, “The purpose of this production is to put the digital world side-by-side and on equal footing with the live performance.”

The statement by itself is flawed but coupled with the flat moments of drama that routinely occurred throughout the performance because of the screens and lack of theatrical stimuli, it felt that his virtuous vision wasn’t yet realized. It’s not a good thing if an audience member needs to ask, “Where should I be looking?” It should be clear based on the story.

Much like Stoic philosopher Seneca once said, “If you’re everywhere, you’re nowhere,” and this performance went nowhere many times and inevitably ended up nowhere as a result.

There were moments that begged the question: “Are we watching a video game or an opera?” This isn’t a good thing because many times, the chaotic mess (or lack thereof) on stage became far too kitschy to watch.

On top of this, the choice to use German instead of English (yet their program titles are in English?) was an odd choice considering the unspoken modus operandi of DO is operatic accessibility. So it seems like operatic modernism only goes so far, then? In any case, the audience was incredibly eclectic, with everyone from men in polo shirts and shorts to women in furs and heels.

It was heartwarming that Sharon, despite his quixotism, successfully created a production that appealed to so many people. This is what opera should be, and something the Met has not yet institutionalized, despite their very best attempts. So sure, Carlos J. Soto’s choice of costumes was incredibly questionable and were essentially glorified leggings and jackets with cheap lamé caps and odd hats for the Valkyries. Wotan got a Marc Jacobs-inspired black ensemble for Wotan. Meanwhile, Goerke wore an outfit with a pink cape. But as a first try at something new, we should commend everyone involved for their work. However, the choice of opera was unwise because a one-act with limited narratival development is not the best.

The Singing

Leading the charge was Christine Goerke, who, in her ebullient yet equipoise way, gave us a sumptuous tone, a rich and luxurious spin, dramaturgical perseverance, and untouchable diction and articulation. Her signature technical trait is her mastery of dynamic contrast and nuanced shading of cadences which provide a sense of finish and conclusion to an otherwise continuously moving act.

In the beginning, as the Valkyries were entering the bombastic surges of orchestral wind and fire, Goerke’s arrival was met with fierce applause, and for good reason. Her interactions with colleagues, much like her 2014 “Elektra,” 2015 “Turandot,” and 2019 “Brünhilde,” (all of which were sung at the Met), were not only organic but believable as well. Each tilt of the head, arm movement, and bodily sway conveyed a sense of purpose. Nothing was just there in Goerke’s choreographic lexicon. However, due to the limited space and the nature of the performance, it appeared she couldn’t fully emote, and at times, her gestures felt too small for Wagner. Compared to her 2019 run, this production paled in comparison, although obviously, nearly all the elements were different.

After this first scene, Goerke’s acting shrank and didn’t really recover until her a cappella lamentation duet, “Was it so shameful?” Her interactions with Wotan were far better than those she had with her Valkyrie sisters, and the close-up shots of her eyes was a magical experience. They radiated energy, producing a stupefying feeling of entanglement, something uncommon in a traditional theatrical experience. However, there were also moments of technical faults; her jaw and tongue shook during some more strenuous passages, and her lower voice was far superior to her upper range throughout the entire night. Regardless, Goerke has earned her place in operatic history, and the legacy she has made for herself is one of biographical importance.

Alan Held (Wotan) was a sensational complement to Goerke, although his presence felt lackluster. Within the previous two (unperformed) acts, you get a sense of why Wotan is angry and the complex reasons he has the violent reaction he does. Taken out of context, Act three just looks like an angry father reacting to something unexplained. Held’s singing was sturdy and consistent, though it took nearly the entire length of his time on stage for him to introduce dynamic contrasts.

Prior to his own touching lament, “Farewell, you bold, glorious child!” his voice took on a one-note demeanor, and you can’t blame Wagner, as articulations are everywhere in the score. That’s not to say Held didn’t emote but rather the opposite. He commanded the stage with his chilling facial expressions and his piercing voice, supercharged with healthy vibrato and methodical vigor.

Paternal until the end, Held’s conception of Wotan as a thoroughly loving father heavily outdid the iffy staging and atmosphere in which he was placed. Sometimes his acting became incredibly stiff as if he didn’t quite know what to do with his body. There could have been more life and a sense of urgency in his movements, but they all went at the same speed and tended to homogenize together until no one movement stood out from the other. But much like Goerke, his career speaks to his incredible mastery of the operatic arts, and it was clear as day that Wotan and Held’s musical life were second nature. Wotan is a role thoroughly embedded in his instrument, his mind, and his heart.

A big standout was Wendy Bryn Harmer, a rising star within the Wagnerian, Verdian, and Straussian operatic world. She has performed Freia (“Das Rheingold”), Senta (“Der Fliegende Holländer”), and Ariadne (“Ariadne Auf Naxos”), all to critical acclaim across the country. Her portrayal of Sieglinde was impeccable. A downside to performing Act three without context is that her relationship with Brünnhilde isn’t well explained.

Her appearance comes out of the blue if you’re not well versed in the overall story. Wearing a sleek and incredibly voguish long-sleeve black dress, Harmer took to the stage modestly, yet performed anything but. Alongside Goerke and her Valkyrie sisters, Harmer rose to the occasion and cast her sizable voice into the house, spinning as she went with youthful vitality and a glamorous edge, which made listening to her a pleasure. The balance of her voice was startling throughout her range. Not a vowel nor an articulation tripped her up, and her beautiful legato never once faltered.

If Harmer maintains her control and technical proficiencies, Europe may knock at her door far sooner than expected. With a taste for nuance and a voice that can handle some of the operatic canon’s most difficult repertoire while still maintaining its vibrant charm, Harmer’s Sieglinde was positively the best thing about the entire night.

No review is complete without mentioning the all-star Valkyries of the evening: Angel Azzarra (Gerhilde), Ann Toomey (Ortlinde), Tamara Mumford (Waltraute), GeDeane Graham (Schwertleite), Jessica Faselt (Helmwige), Leah Dexter (Siegrune), Maya Lahyani (Grimgerde), and Krysty Swann (Rossweisse). Each one of these artists was absolutely brilliant in their roles. A ringing, vibrato-laden torrent of golden sound emanated from each during the opening scene. Hearty and jovial hojotoho’s soared through the air, while solid diction and resonant lyricism complimented the tension that followed.

All told, it was an evening full of ingenuity and all-star singing. Detroit Opera’s sensational, virtual-reality production of “The Valkyries” is a taste of the future of opera itself, and if Yuval Sharon continues down this road, there’s a place in operatic history waiting for him. In this novel conception, where Wagner meets “Tron,” Detroit Opera has proved itself to be truly ahead of its time.