Chautauqua Opera 2017 Review – Don Pasquale: A Top-Notch Cast & Production Make For An Enjoyable Evening of Donizetti’s Comic Masterwork

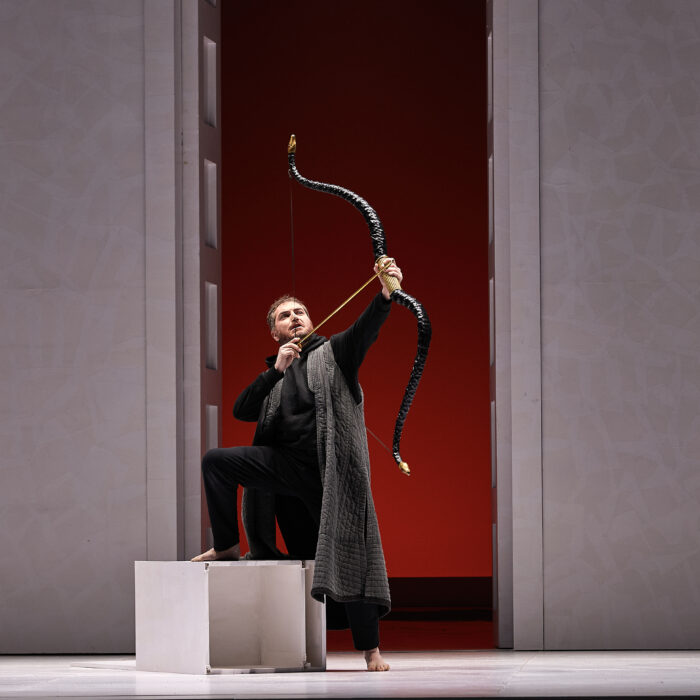

By John S. TwinamIn what appears to be a trend this summer, Chautauqua Opera’s production of Donizetti’s classic opera buffa “Don Pasquale” was distinguished by its treatment of a non-title character, in this case the gorgeous lyric baritone of Kyle Pfortmiller as Dr. Malatesta. Under the direction of David Schweizer, Malatesta doesn’t just engineer the complicated ruse designed to unite lovers Norina (Laura Soto-Bayomi,) and Ernesto (Arnold Livingston Geis) and thwart the foolish ambitions of the aged Don Pasquale (brilliant buffo bass Stefano de Peppo), he controlled the entire theater. In what appears to be another trend (sending performers out on stage before the orchestra has even tuned up, seen at Glimmerglass last season in “The Thieving Magpie” and this season in St. Louis in “The Grapes of Wrath” and Des Moines in “A Little Night Music”), Pfortmiller appeared on stage while the house lights were still up and the audience still buzzing. The orchestra began tuning only on his command, and when he grew bored with that, with a sweep of his arm and a wave of his cane, the house lights came down, conductor Steven Osgood literally popped up in the pit, and Malatesta was nearly blown off the stage by the huge opening phrase of the overture.

Faithful on One Hand, Untrusting on the Other

And there he remained throughout the overture, as the Chautauqua Opera Orchestra melted into some of Donizetti’s most confectionary melodies, so light and delicate and simple they require enormous artistry to truly elevate. To prepare for last night, I watched Muti’s production at La Scala on YouTube; the extreme liberties he took with tempo and meter in service of his vision sometimes reminded me of my high school choir director messing with “Lullay My Liking” just to make sure we were paying close attention. Osgood is generally more faithful to the text and score, yet with minimal portamento still managed to achieve the airiness and grace in the strings and winds without which Donizetti can become a bit plodding. Without a real story to tell as the overture continued, Malatesta needed something to do as the music played on, and so was given a small desk and chair at which to do imaginary work. While establishing the theme of Malatesta as the puppet master for the evening, I’m quite sure this pantomime throughout the overture is what one couple was referring to at intermission, when the wife complained that the company “didn’t trust the music, “ and the husband replied, “Or the audience. Oh well, a lot of companies do it.”

In Complete Command

As the overture wound down, Pfortmiller sprang back into action, pulling on imaginary ropes to open a series of red plastic curtains. At his command, stagehands appeared to dress the set for scene 1, which from the Edwardian costumes and tattered Victorian settee appeared to be later than the early 19th century identified in the libretto. With shredded furniture and pictures on the wall askew, Don Pasquale’s residence does not appear to be that of a man of means. Surrounded by his three loyal, shaky, shuffling, zombie-like servants, Pasquale is plotting against his nephew, Ernesto for refusing the hand of the wealthy woman chosen for him in favor of his impoverished beloved, Norina. The first of many brilliant comic moments occurs when Malatesta arrives to set his own plot in motion. Pfortmiller’s rich baritone filled Norton Hall in “Bella siccome un angelo” as he described Pasquale’s bride-to-be using a sly, slightly naughty demeanor. De Peppo then took command of the stage to express the vigor of his newly-inflamed loins in “Ah, un foco insolita.” He totally won me over to his side, and when Ernesto slouched in, young louche that he was, with the attitude of boredom and disdain common to youth being castigated by their elders, I stayed with the Don. Not until Ernesto leapt off the sofa and launched into a passionate defense of his love for Norina did he become the romantic hero. Exquisitely tailored, in sharp contrast to the ragged ensembles of the rest of the household, Geis’ gleaming tone brought vigor to what can be a bit of a sad sack, “woe is me” series of arias, as he continued to be buffeted by events he neither understood nor controlled.

The Turn of the Shrew

With all the leading men having established a high standard in the first scene, Soto-Bayomi, making the jump to leading lady after two years as a Chautauqua Opera Studio Artist, entered in her unmentionables and thrilled the audience with her rendition of “So anch’io la virtu magica,” which is basically Norina’s “Una voce poca fa.” In what was the first clear indication that we were in modern times, and not the Edwardian era as I suspected, the book Norina usually reads during her introductory aria was replaced by a glossy tabloid gossip rag; that impression was later confirmed when Ernesto wheeled in a hard shell spinner suitcase, sported a backpack, and drank from his water bottle on his way out of his uncle’s house. Those modern touches could have made Malatesta’s exaggerated horror at bursting in on Norina in a state of dishabille somewhat out of place, but Pfortmiller’s charming manner overcame any awkwardness. His comic duet with Soto-Bayomi, as she proposed and he rejected various approaches to solving their dilemma, showed the chemistry Pfortmiller displayed with de Peppo had been no fluke, and that all the principals were well-prepared to carry the farce to its conclusion.

In a bit of an inversion of the Samantha/Serena syndrome, feisty Norina is transformed into demure Sofronia, Malatesta’s sister straight out of the convent. Pasquale is smitten and, in a fit of passion, turns control of his house and half his fortune over to his new bogus bride. He enjoys about a half a second of wedded bliss before Sofronia becomes a shrew who mercilessly bullies the dumbfounded Don. De Peppo was in his glory in Act III, calling on all his comic gifts to portray Pasquale’s stupefied bewilderment as his once tranquil household spins out of control around him. He teamed up with Pfortmiller again, delivering a blistering “Cheti, cheti, immantinent”

so precise and so rapid that the subtitles, to the audience’s amusement, simply couldn’t keep up.

Playing with audiences sympathies can be a dangerous thing, especially an audience of wealthy older men being asked to accept the idea that foolish seniors should renounce any notion of marrying sweet young things. Being of a certain age myself, I perhaps felt more sympathy for the Don than intended. But it’s a comedy, and in the end, as it must, true love wins out and the bumptious male Marschallin has a sudden change of heart and graciously stands aside in favor of the young couple amid general rejoicing.