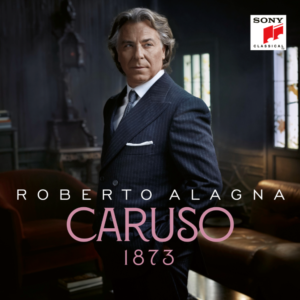

Long is the shadow that Enrico Caruso and his recordings cast on the history of singing.

At a critical juncture of technological advance, they inspired not only an epigonal school of tenors (whose famous “sobs” entered the mainstream of verismo singing) but also a whole array of cultural byproducts that range from semi-fictional biopics to Lucio Dalla’s global hit.

On a more philosophical level, however, Caruso created the myth of the Italian tenor that every generation or so is striving to incarnate. In his recent album Roberto Alagna certainly paraphrases this legacy, nudging the listener into his very own history lesson with many a clin d’œil.

And yet there is no sense of urgency after an already distinguished career that makes Alagna adopt a more casual or, in this case, reverential tone. It counts as the album’s greatest strength; its 70 minutes are an enjoyable and charming homage that is deliberating passing judgment on Alagna’s place in an illustrious lineage that counts – as Caruso’s heirs – no other than the greatest of the greats.

The Great Caruso

It it a very hard undertaking to rightfully assess the merits of his new album. With Alagna’s decision to produce a full-throated sound – analogous to early recording aesthetics – he also ventures into an understanding of opera that is largely foreign to modern day standards.

For the album replicates the 19th century practice of national styles of singing that are not by any means tied to a specific repertoire. Thus one finds the Italian translation of Bizet’s “Je crois entendre encore” and Massenet’s “En fermant les yeux” sung – as was customary – in a rather forward manner devoid of the vocal artifice traditionally heard by French interpreters.

In the former case, Alagna substitutes the orchestra for a mere piano accompaniment. This is all the more interesting, as there is evidence of two orchestra versions recorded in New York and Camden, NJ in January and March of 1908 respectively.

However, these takes have – to my knowledge – never been released and Alagna uses as his reference the 1904 version produced by the Gramophone Company. What becomes immediately clear is his attempt to strike the fine balance between imitation and originality; this extends to his relying on the chest voice even in high tessitura passages such as the arch on “folli ebbrezze.”

Similarly, he ends the aria in falsetto following the prototype rather than his own artistic instincts. Caruso had indeed not fully developed control of his high notes yet and the falsetto proved a welcome alternative; the interpolated high C in the 1905 recording of Mascagni’s “Brindisi,” for instance, falls into the same category of mixed sounds that do not altogether convince – at least not under the microscope of modern recording technology.

“Santa Lucia”

The two sacred arias “Domine Deus” and “Pietà Signore,” though popular and widely played even in today’s concert repertoire, might well be the most illustrative examples of the stylistic changes Alagna decided to undergo.

Here more than ever do the accelerated tempi add a sense of nostalgia so peculiar to the acoustic era. Alagna also manages the full-voiced sound production very well, compromising little to nothing on his phrasing and the melodic line. And yet, after multiple listenings, they appear to grow hard on the ear, as the dynamic range is small especially in “Domine Deus.”

What is more they have the verve of showpieces and the emotional or spiritual implications remain rather negligible, faultless as the singing may be. This leaves no doubt as to the most successful track of the album: “Santa Lucia” is a sparkling rendition where the sentiment matches the natural inclinations of a bright timbre.

Alagna dominates the song while certainly hearing Caruso at the back of his mind. It is after all recorded in the same tempo as its pendant, but the differences are nonetheless paramount. One might say lighter or more lyrical than the legato-heavy effluences of the Neapolitan tenor.

Whatever the case, it points towards a general tendency; and the more he asserts himself the better he fares. A reverse example can be found in Alagna’s treatment of “Mattinata” where his lines seem to drag in a somewhat uncomfortable attempt to match the elder tenor’s rhythm and caprices at the conclusion.

The Grand Tradition

On another, more historical note “Caruso” features some curiosities such as the bass aria from Puccini’s “La Bohème” and “Tu ca nun chiagne” recorded on a wax cylinder. The former has integrated the quasi mythological image of Caruso who, facing away from the public, performed the so-called “Coat Song” instead of the laryngitis-stricken bass Andrés de Segurola.

Alagna, while not displaying the same heft, surprises with a well-centered voice and warm phrasing. He is also very secure in the trio with Aleksandra Kurzak and Rafa Siwek whose monolithic Hermit I find particularly appealing.

As for the above mentioned “Tu ca nun chiagne” it is a potent reminder of the historical distance that separates Sony Classical’s lavish engineering from the pioneering works of the acoustic age. This divide – technological and epochal – is temporarily suspended in some 20 tracks of nostalgic enjoyment, paired with rarer moments of musical blandness where the role model is leaving Alagna behind.

That being said, neither his voice nor musicality are to be faulted; it is rather a change in taste that sometimes cracks through the 100 year-old facade of what is – in the famous words of John Steane – the Grand Tradition of Singing.

Categories

DVD and CD Reviews