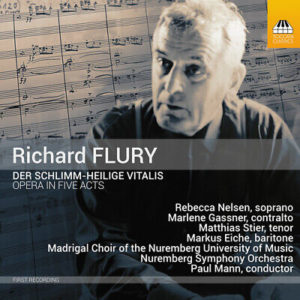

CD Review: Richard Flury’s ‘Der schlimm-heilige Vitalis’

By Bob DieschburgIn line with their commitment to promote the works of unrecorded and near-forgotten composers, the forces of the British Toccata Music Group have, since 2017, dedicated their attention to Richard Flury, a “Swiss Romantic” (as the title of Chris Walton’s biography reads) and creator of four operas written in truly eclectic and, to some extent, anachronistic fashion.

“Der schlimm-heilige Vitalis” is not only their latest release and a world premiere recording, but also the last opera Flury composed before his death in Biberist in the canton of Solothurn in 1967. Translating as “Lustful Brother Vitalis” it narrates the zealous endeavor of its titural character to eradicate the sinfulness of the local prostitute Jucunda – only to be seduced by the young Jole into admitting his desires, cathartically breaking his vow, and, an apostate, celebrating marriage.

Hedonism, Crudely Retold

The story is based on the eponymous tale by Gottfried Keller which the Swiss author published as part of a (pseudo-)hedonist set of novellas: bold, erotic, and often scandalous in content, but counterbalanced by the positively atheist substrate of Ludwig Feuerbach’s philosophy. The latter is essential to the broader understanding of Keller’s text, but very poorly translates to the libretto that Franz Johann Danz wrote in preparation of the opera. Setting, for the most part, an overtly sexist and voyeuristic tone, the work is devoid of the merriness which the Viennese operetta for scenarios of similar lasciviousness so easily achieves.

Take the second-act confrontation between Vitalis and Jucunda in which the libretto directs her to “tear off her top and stand half-naked in front of the trembling Vitalis” who, in the end, “ties her to the bed” to an exhausted “Gloria in excelsis Deo.” Nothing could be further from modern sensitivities, let alone poetic virtue.

What is more, when Danz does not hurt the decorum, he resorts to some kind of pastiche verse which the literary student will recognize in the grand finale. Here, the theme of love’s omnipotence echoes not only the wording, but also the trochaic meter of “An die Freude” (the ending of “Fidelio” also resonates) paired with the so-called “chorus mysticus” from Goethe’s “Faust.” All the while, Danz remains strangely shallow and derivative at best.

A Swiss Romantic

A self-professed Romantic, Richard Flury remains skeptical of the tonal revolutions of Schönberg and the Viennese School, modulating his chromatic effects only for the sake of atmosphere and not intellectual or constructivist coquetry. His 1923 Symphony No.1 in D-minor may best exemplify the neo-Romantic idiom in which he operates (and which is vaguely reminiscent of the Lithuanian Čiurlionis’ orchestral style).

“Der schlimm-heilige Vitalis,” however, retreats into the soundscape of a small-scale orchestra, which Paul Mann, the conductor of the Toccato release, attributes to the limited capacities of the Solothurn City Theatre in 1963. Indeed, the instrumentation is much more akin to the style of early 20th century operettas than the rest of Flury’s oeuvre or, for that matter, the intermezzo in Act four might suggest: it is simple (simplistic some might say), and coherent with the drama and psychological state of the characters.

The violins, for instance, quiver to translate the inner tension of the friar, second the vocal line of Jole in her relentless efforts to seduce Vitalis while, on a different level, reflecting the composer’s own taste for the virtuosic as well as his background as an instrumentalist.

I will concede that “Der schlimm-heilige Vitalis” does not abound with inventiveness and its most effective ideas are rather short lived. To some extent this has to do with Flury’s rejection of the leitmotif system, which makes the orchestral texture appear less dense.

As for individual arias, the brindisi-like tune of “Ihr Leut’! Ein Trunk bis auf der Kanne Grund” counts among “Vitalis’” most resourceful tunes, playing with the contrast between debauchery on the one hand and the serenity of the psalm on the other.

Impeccable Musicianship

As mentioned before, the score is leanly orchestrated but still boasts a significant number of roles extending beyond the mere function of comprimari: The libretto lists 16 roles not including the mixed chorus of “people, soldiers, and citizens.” It therefore goes without saying that the consistently high quality of the cast is deserving of every accolade.

Markus Eiche as the Soldier, for instance, fills his introductory aria with charm and esprit. In “Wie das Kätzchen auf dem Dache” he demonstrates comedic intuition, delivering the high-tessitura romance with a delightful staccato leading up to the onomatopoeic repetition of “Ju-Ju-Ju-Jucunda.”

The Texan Rebecca Nelsen lends her youthful soprano to the witty character of Jole. Phrasing intelligently she creates the most dynamic portrayal of all the cast involved, lifting the youthful heroine beyond the gender-based stereotypes that a less incisive interpreter might otherwise have suffered from. Particularly, her ability to have the lightheartedness of her role prevail in true operetta-fashion is an achievement of itself – even more so when the crudeness of the libretto does not do her role any favors (as in the seduction scene of Act four).

The same goes for Marlene Gaßner’s Jucunda whose waltz “Ja, Jucunda” is a somewhat ungrateful task, eclectic in its reference to the “Habanera” but without its melodic ingenuity. It is a shame really, as I believe Gaßner’s timbre to be instantly recognizable and very apt to produce gripping characterizations in the more established repertoire. Her best moments in “Der schlimm-heilige Vitalis,” meanwhile, are heard in the duet with the title character.

The latter benefits from the versatile, baritonally-colored tenor voice of Matthias Stier. The Swiss Stier excels in the duets as well as in the cantabile of “O Sancta Maria” in which breath control and fine dynamic shading give a fair measure of his musicianship. He manages the part impeccably (it is by no means an easy one) and convincingly shows the transformation from religious zealousness to secular desire embedded, that is, within the matrimonial context of his love for Jole.

Finally, the concise but no less spirited conducting of Paul Mann leads the Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra to give a crystal-clear performance that binds the otherwise uneven and – in parts – heterogeneous score into an overarching vision.

In short, Toccata’s release of “Der schlimm-heilige Vitalis” cannot be faulted for its musical execution. It does not, however, belie the inherent deficits of a score that is lukewarm at best and a libretto which, nowadays more than ever, remains offensive to the point of canceling out any philosophical or broadly moral overtones Keller’s novella had.

As such, it does not commend itself to being more than a curiosity and a listen to Flury’s many symphonies and concertos (available on the same label) will hold better value to Swiss musical history than the last of his operatic works ever could.