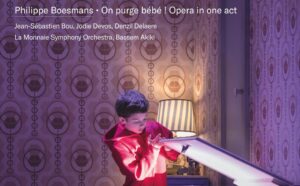

CD Review: Philippe Boesmans’ ‘On purge bébé!’

By Joe Cadagin“This could be my last opera,” predicted Philippe Boesmans in February of last year, just two months before his death at 85. “I’ve done tragedies…so I decided that I have to finish with total lightness, total insouciance.” Virtually unknown in the U.S., the Belgian composer garnered European success with exquisite settings of serious drama: Schnitzler’s “Reigen“ (1993), Shakespeare’s “Winter’s Tale” (1999), and Strindberg’s “Miss Julie” (2005). But in a Verdian burst of geriatric productivity, Boesmans bid a wickedly irreverent farewell with his eighth and final opera, recorded by Fuga Libera at its 2022 Brussels premiere. Posthumously completed by his former student, Benoît Mernier, “On purge bébé!” tackles the highly irregular subject of constipation.

The libretto by director Richard Brunel is based on a 1910 play by Georges Feydeau, better known in its 1931 film adaptation by Jean Renoir. The title translates clumsily into English — something along the lines of “Let’s purge baby!” It’s no infant we’re dealing with, but a smothered seven-year-old, Toto, who wakes up with a mild case of defecatory difficulty. His helicopter mother, Madame Follavoine, demands her husband administer a laxative to their reluctant son. But Monsieur Follavoine, a porcelain producer, is busy trying to land an exclusive contract to manufacture chamber pots for the French army. Hilarity ensues as the coarser affairs of child rearing intrude on daddy’s business meeting.

Feydeau’s farce scathingly satirizes the hypocrisies of bourgeois domesticity. Madame Follavoine can’t bring herself to name Toto’s affliction, euphemistically telling her husband the boy “hasn’t been.” And Monsieur can barely stand the sight of the slop bucket his wife is emptying. Yet the merde of their miserable family life is put on shameless display for the military official Chouilloux, who uncomfortably witnesses a dissolving marriage and, in Toto, a little neurotic in the making.

With his penultimate stage work, “Pinocchio” (2017), Boesmans brilliantly demonstrated the comedic potential of his ebullient style. “On purge bébé!” seems to cram all the mischievous energy of that previous, two-hour opera into a single act. Indeed, the score is bursting with sonic hyperactivity. Boesmans’ musical language is cartoonishly mercurial, in the vein of Ravel’s “L’enfant et les sortilèges” or Poulenc’s “Les mamelles de Tirésias” — either of which would pair splendidly with this work on a double bill. Every onstage action is accompanied by manic Mickey Mousing or instrumental sound effects from the La Monnaie Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Bassem Akiki. The players provide a running commentary on the vocalists’ patter-paced dialogue, mimicking and punctuating the Follavoines’ incessant bickering.

Mercifully absent are any overt, whoopie-cushion imitations of bodily functions. Like the author of the original play, Boesmans is tactfully subtle in how he approaches the scatological. Toto’s constipation, for instance, is represented by queasy, constricted-sounding harmonics on solo violin. For Chouilloux’s enteritis, on the other hand, the ensemble executes a fast-and-loose descending scale — “the runs,” if you will. While there aren’t any excremental gross-out moments, Boesmans does tend to nauseate in other ways. The opera’s unrelenting, merry-go-round frenzy leaves one feeling rather dizzy. And as the plot grows progressively crazy, there’s nowhere to ramp up to since we’re set in high gear from the get-go.

If a tad formless, the opera is granted some structure through Boesmans’ clever employment of leitmotifs quoted from existing compositions. Monsieur Follavoine promises to track down the location of the Hebrides for Toto, and his geographical hunt is accompanied by a bouncy, fugue-like development of Mendelssohn’s “Hebrides” Overture. Later, as he shows off his supposedly unbreakable chamber pot, Wagner’s grail theme from Parsifal rises from the orchestra with mock solemnity. When he dashes the dish to pieces in a failed demonstration of its durability, the motive is transferred to tinkling piano and chimes that conjure a thousand bits of chipped chinaware.

One particularly dark musical reference comes at the end, in the short portion of the score completed by Benoît Mernier. As the parents’ row spirals out of control, Toto is left alone in a tense moment accompanied by the “Hebrides” Overture theme. Only, it’s twisted to resemble an eerie motive from Strauss’ “Salome” — the one that repeats as the princess gazes lustfully into John the Baptist’s dead eyes. The implication seems to be that the Follavoines are headed down the same self-destructive path as opera’s arch-dysfunctional family. It’s unclear whether this allusion was Mernier’s idea, but it definitely gels with Boesmans’ concept for the work: “maliciousness and a complete lack of poetry and spirituality.”

Stage director Richard Brunel undoubtedly picked up on this rather Freudian angle and cast an adult in the spoken role of Toto, as if a troubled adult were working through his childhood traumas. To be sure, precocious child actors are downright irritating. But it’s infinitely more obnoxious hearing a grown man put on a baby voice.

The sung performances, however, are first-rate — especially that of soprano Jodie Devos, who carries the show as Madame Follavoine. Boesmans sets her tessitura intentionally high to evoke a shrieking housewife. Yet Devos defies this shrewish stereotyping, hitting impeccable bell-tone top notes and tossing off sprightly flights of coloratura reminiscent of Bernstein’s “Glitter and be gay.” If by no means nagging, the soprano conveys a certain feistiness and even a charming deviousness in her portrayal. She dons a faux-pathetic wail, for instance, whenever Madame attempts to guilt her husband for being a neglectful father.

As Monsieur Follavoine, Jean-Sébastien Bou is a brilliant foil for Devos — bumbling, self-important, and braggadocious. The baritone’s air of deluded confidence during his salesman’s pitch is particularly comical, especially when he proceeds to obliterate two chamber pots in a row. Denzil Delaere is an adorably clueless Chouilloux, the potential military investor. In a parody of a sentimental Massenet aria, he nostalgically reminisces about his gastrointestinal spa treatment, flipping into tender head voice as if he were fondly remembering a long-lost love. Mezzo Sophie Pondjiclis and bass Jérôme Varnier as Madame Chouilloux and her cousin are an amusingly pompous buffa duo, calling to mind Marcellina and Bartolo from “Figaro.”

The CD booklet includes a QR code leading to the online French libretto, but it’s only translated into Dutch. Even if your French is rudimentary, it’s relatively easy to follow along with the text. Non-speakers might consider watching the subtitled Criterion Collection DVD of Renoir’s film before giving the opera a listen.