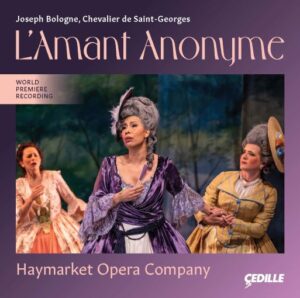

CD Review: Joseph Bologne’s “L’amant anonyme”

By Bob DieschburgThe life of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799) reads like an operatic plot set in the decades between the heyday of the Ancien Régime and the interim years of the Directorate. It involved some of France’s most illustrious figures, including Marie-Antoinette, whom he frequented in Versailles after being famously denied the directorship at the Académie Royale de Musique.

Similarly, he knew François-Joseph Gossec and remained friendly with musicians the likes of Mozart and Salieri while stunning, as a virtuoso fencer, international sword masters Domenico and Harry Angelo, as much as the revolutionary Louis-Philippe II to name but a few.

Yet it is as one of the earliest biracial composers that the Chevalier asserts his historical significance. Nicknamed “l’inimitable” and “the Black Mozart” as a token to his virtuoso skills (both with the fencing foil and the violin) he is credited with over 200 compositions of which the symphonies and concertos have, so far, received the most attention on disc.

With “L’amant anonyme” the balance shifts, as the label of Cedille Records releases Saint-George’s third and only surviving opera for the very first time.

Qui Pro Quo

Based on Madame de Genlis’ play of the same name, “L’amant anonyme” revolves around the theme of a comedic misunderstanding or qui pro quo in the vein of Molière and Marivaux. Its premise, however, is more tenuous and lacks the dramatic elements which make the denouement of pieces like “L’avare” or “Le bourgeois gentilhomme” (set to the incidental music of none other than Lully) so cathartic and memorable.

For “L’amant anonyme” stages a love triangle which, in reality, does not exist. It comprises the noblewoman Léontine as well as Valcour who doubles as the title-giving anonymous lover to test the sincerity of her feelings – or, indeed, her virtue in love, which the choir somewhat amusingly turns into a hymn to Frenchness.

Unlike in the near-contemporary “Finta giardiniera” there is no antagonist and the overall stakes are surprisingly low. Yet it is tempting to see in the confidant Ophémon a musical predecessor to the Rossinian Figaro, knowing of course that its model, Beaumarchais’ “Le Barbier de Seville,” was published as early as 1775 (“L’amant anonyme” premiered in 1780).

A Palimpsest of Danses

Musically, the Chevalier overcomes any weaknesses in the libretto by adopting a palimpsest of dance forms to illustrate the action and, in true rococo fashion, trace the emotional progression of its characters in virtuosic variations of the orchestral texture as much as the vocal writing.

Léontine’s ariette “son amour, sa constance extrême,” for instance, finishes with two high Cs in the da capo section of “non, rien ne peut toucher mon coeur” to mark her increased resolve not to submit to the unknown lover’s advances.

In the wonderfully informative booklet, Mark Clague describes the score’s intertwinement with the narrative in much greater detail than I would be able to retrace within the narrow scope of the present review. Suffice to say, it gives a valuable account of the technical and interpretive difficulties the members of the Haymarket Opera Company have to face.

The Anonymous Lover Regained

The latter starts with the high tessitura of the main roles, not to mention the ornaments which both Nicole Cabell and Geoffrey Agpalo as Léontine and Valcour master admirably. Notably, the warm and simultaneously veiled sound of Agpalo’s tenor is a sheer pleasure to listen to. It is sensitive, melancholic, and joyfully expansive at will while it blends in the duets with the grainy bass-baritone of David Govertsen.

He is a sympathetic Ophémon, less imaginative than Agpalo in the recitatives but phrasing smoothly in his second-act aria “aimer sans pouvoir le dire.” Similarly, Erica Schuller and Michael St. Peter fill the secondary roles of Jeannette and Colin with remarkable ease, Schuller’s airy coloraturas deserving special praise.

However, the most remarkable contribution to “L’amant anonyme” comes from the American Nicole Cabell, as she navigates the considerable extensions as well as the pitfalls of the Chevalier’s virtuoso demands without ever compromising the integrity of her line and honeyed tone. She is equally inventive in the spoken dialogue where, a true comedienne, she processes Léontine’s falling in love.

Constitutive to the success of “L’amant anonyme” is also Craig Trompeter’s historically informed approach to Saint-George’s score. He conducts the Company’s orchestra with firm hand, moderately fast tempi, and clear attention to chromatic detail, thus defining the performing standards of his oeuvre for decades to come.

More importantly perhaps, he is instrumental in realigning Joseph Bologne with the finest composers of his generation, Mozart, Salieri, Gossec, Gluck, and others.