Caramoor 2018 Review: Atalanta

Handel’s Music Given A Special Rendition In Outdoor Setting

By Matt CostelloLast summer, amidst Caramoor’s summer festival, I got a chance to informally talk to Jeff Haydon, the CEO of the music and arts center that happens to be in my home town of Katonah.

I was told that Caramoor’s long-time successful operatic series “Bel Canto at Caramoor,” headed by Will Crutchfield, would be leaving. Crutchfield, after decades at Caramoor, was moving to the nearby State University of New York at Purchase.

Crutchfield had passionately presented archival performances of both familiar and lesser known gems of the bel canto repertory. He also on occasion, with the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, would tackle some pieces that were decidedly of a different order such a Verdi’s “Otello” and “Don Carlos.”

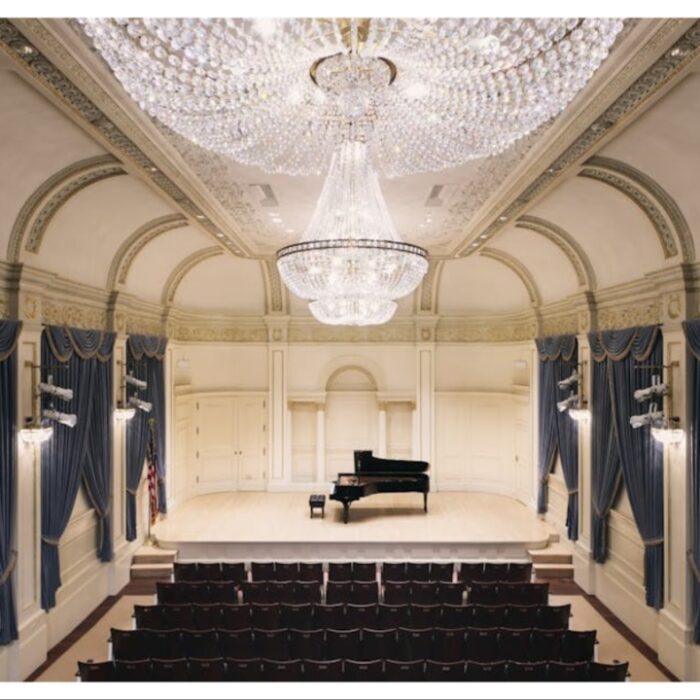

But what of the Caramoor program, I asked? I was relieved to hear that opera at the summer festival would not be abandoned, that companies would be invited to the Venetian Theater stage, a beautiful setting, albeit with an architecturally limited stage size, to mount productions.

And the first such post-Crutchfield opera on that stage, Handel’s “Atalanta” debuted, on recent hot Sunday afternoon, in a production that, well, if there was a strong case to be made for the baroque work, this was the ensemble and artists to do it.

What Story?

Many know Handel mostly from his familiar pieces, such as his Music for the Royal Fireworks or the holiday perennial, Messiah. But Baroque opera has a structure that is both stately, formulaic (to some) — and yet can be dramatic, albeit in different ways from the mainstream canon.

The vocals adorned by embellishments are where the real fireworks of the piece occur. And once you let yourself drift into the world of baroque opera and that performance style, the work can attain a rather special beauty.

The libretto (author unknown) of “Atalanta” is a pastoral story of mistaken identities, misplaced ardor, with a wild boar threatening all (that event left largely to one’s imagination), and finally, hours later, a story where love triumphs all.

One thing I noted is that even with translation of all the Italian dialogue, I doubt one could actually follow said story without having read the synopsis.

It is only really with the synopsis in hand that one can learn that this “shepherd” is actually the king, and the other shepherdess is a princess, both seeking, it would seem, a summer’s day unrecognized outside the palace walls.

We call all relate, no? There is also another couple of genuine shepherds, again with a conflicted trail to their true love.

But when I explained to someone attending with me that one of the sopranos was the king, a role designed for a castrato, it is only with the help of the synopsis that I knew such “insider” information. So, story-wise, I would argue that it is perfectly “okay” to not pay too much attention to the plot and lyrics.

Instead, on a hazy summer afternoon, simply listen to the sound. Because that was indeed special.

But the Music…

The opera was performed by Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, led by Nicholas McGegan.

McGegan and the orchestra are extremely experienced with this music, specializing in the baroque to global acclaim for their accurate and passionate performances. Numerous recordings and awards have come their way (including a “live” “Atalanta”), and I imagine there could be no group better to make this centuries-old music come to vibrant life.

The orchestra is small, by operatic standards, and features instruments not often heard, such as the theorbo and baroque horn. Not many programs, by the way, list the orchestra members and the exact provenance of their period-authentic instruments.

And while the music might seem to lack the more visceral emotional power of classical and certainly romantic works to come, there is, as said, both a stately beauty and emotional power in Handel’s work here, composed specially for the then newly-built Covent Garden.

And when the equally experienced singers enter after the overture, we enter a different, dare I say, rare world.

Three Female Leads

The singers share a background both with the baroque and this specific orchestra and its conductor.

The three female leads —- sopranos Sherezade Panthaki as Atalanta and Amy Freston as the King, Meleagro, with mezzo Cecile van de Sant as the real shepherdess, Irene — produced sounds of crystalline clarity, beauty, that had me dreaming of reclining on a grassy lawn, and letting this slim, pastoral tale with such heavenly voices accompany a wonderful chilled Sauvignon Blanc.

The embellishments made a convincing case for why this style of opera and the singing – with the rippling, cascading fioritura— was something to relish from all three women, even as it is remains so distant from the more modern operatic masterpieces we know and love.

With both van de Sant and Freston commanding that stage with their perfect and sumptuous singing, producing real sparks, it was Panthaki as Atalanta who – I am sure — could be heard well into the woods that surround the gorgeous grounds of the Caramoor site. Her soaring voice, both thrilling and powerful.

While Panthaki certainly masters this baroque style, I would welcome hearing that voice in other repertoire (and she has, in fact, sung in pieces such as “Carmina Burana”, “Beethoven’s 9th”, and Rachmaninoff’s “Vocalise”).

Likewise, van de Sant’s mezzo had a bell-like, ethereal sound, the beauty immense, regardless of the often endlessly repeated and mundane lyrics being sung, with singing this beautiful, just maybe, who cares about the words?

And in the role designed for a castrato, Freston was both gamine and plucky, while also sending her soprano voice rippling up and down with what seemed like ease. (But in truth, such signing from all the cast speaks of a tremendous attention to the music and a major, matching talent.)

The Male Leads

The women were equally matched with the three male leads — not counting, of course, the king, who technically, back in the day, would have been a male castrato.

Irene’s father Nicandro was smoothly and warmly sung by the stand-out baritone, Philip Cutlip. Isaiah’s Bell’s lovelorn tenor as the realshepherd, Aminta, was sung with grace and power.

And not to forget the late-to-the-party god Mecurio, ably sung by Davone Tines, who arrives to kick the festive opera’s end into high gear.

And the vocal treasures in the score continue to abound over the course of the opera, each act with exciting highlights such as the duet in Act three with Atalanta and Maleagro. The interplay of all the singers throughout was nothing short of sublime.

As so often with the great musical festivals of summer, nature plays a part her too, not only in the story of “Atalanta” but also in the Caramoor surroundings where a gentle breeze could be heard rustling the trees just outside the tent of the Venetian Theatre.

As the audience traveled back to a time where there was on offer a very different beauty, originally designed for royals, but here to be discovered and enjoyed by all.