Bayreuth Festival 2023 Review: Parsifal

Jay Scheib’s Production of Wagner’s Final Masterpiece is a Confusing Mess

By Christina Waters(Photo Credit: Enrico Nawarth / Bayreuth Festival)

It would be difficult to exaggerate the ways in which Jay Scheib‘s “Parsifal” at Bayreuth 2023 fails its sublime musical roots. From amateurish digital enhancement to bargain basement stagings, this opera sold out its mission in every way, save for one factor (more much later).

In the front row of the loge section, I had easily a meter of leg room. A luxury in the midst of a heat wave in an un-air-conditioned hall. This turned out to be one of the only positive aspects of the much-hyped “Parsifal” experience. Customized AR (augmented reality) glasses provided 300 patrons a digital feed of oft-irrelevant, always obfuscating computer-generated images. Starting with a promising shower of points of light, tiny stars filled the entire panoramic “view” provided by the glasses during the breathtaking opening chords.

But then came rotating tree branches, aggressive swans, and bouncing skulls with flapping mandibles in shades of purple and pink. Snakes slithering or biting their own tails as persistent orobori then seemed to attack the viewer. Tree branches, paper maché flowers, more paper maché flowers, and worst of all, primitive motion-capture animations of male and female figures walking as if devised in a pre-CGI era. This may have been a post-internet style choice, as if to tell the viewer that in the future cheap animation, cheap AI, will be ubiquitous. There will be no real flowers. No fleshed out creatures. Or it may have been due to the failure of imagination and financial resources. Whatever the reasons, the effects were, from start to finish a barrage of tacky, view-obstructing clutter. But the view of the stage itself was arguably worse!

Mixed Performances

The glasses themselves were literally hot and heavy, so much so that many patrons in my balcony section had to resort to placing handkerchiefs on the bridge of their noses, cushioning the heavy AR glasses, just to endure the hot plastic. Many did as I did—after my digital feed blacked out for the second time mid-Act 2—and simply removed the glasses. Responsibility for the incomprehensible sets goes to Mimi Lien, a MacArthur “genius award” recipient. Inane costumes by Meentje Nielsen, referencing part surfer aesthetic, part military camouflage gear similarly intruded without heightening. The storytelling itself, convoluted even on a good day, was all but lost in the bewildering choices made by all the visual designers, from arbitrary AI graphics to vaguely post-apocalyptic color schemes.

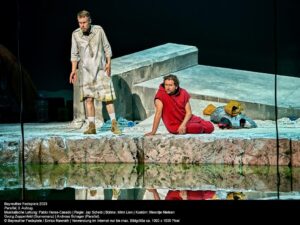

The various Grail supplicants, Gurnemanz (a masterful Georg Zeppenfeld), and poor bleeding Amfortas (a lurching Derek Welton) act out their quest at the edges of a shallow pool of green liquid (Fukushima?), while awaiting salvation in the form of the holy Fool, Parsifal (Andreas Schager).

Baritone Jordan Shanahan made a playful wizard Klingsor, with acting fireworks to match his tenacious vocals.

Ekaterina Gubanova seemed to still be finding her way through the admittedly complex and spiritually ambiguous role of Kundry. She was technically on the mark, yet failed to flower into emotional authenticity.

And while the renowned heldentenor Andreas Schager had youthful Parsifalian energy to burn—even up to the end—he allowed his top notes to decay into a vibrato the width of Bayreuth, especially at the top end of his incredible range. Schager might have been pacing himself, since he went on to soar through the role of Siegfried the very next night.

Most satisfying of all the vocal performances was the Gurnemanz of German bass Georg Zeppenfeld (who sang Hundig the evening beforehand). His elegant voice and serene gestures created a welcome through line of power and conviction.

Forming the background were stage-wide, live video projections of the singers as they moved about the stage. If this was an attempt to providing visual interest it only succeeded in providing redundancy. It too seemed a cheap way to fill up the space, rather than create illuminating reference to the on-stage narrative. The post-apocalyptic theme was complicated by the middle act, in which a red-suited Klingsor attempts to seduce Parsifal with a harem of flowermaidens in dollar store costumes. These temptresses had been outfitted as hippie hookers, decorated with body paint and scanty sarongs, lounging desperately at the edges of the green pool, over which hovered a circular ring. Was this a helicopter pad? a primitive religious symbol? Did the stage designer even know?

After a great deal of fine singing on the part of the Bayreuth Opera chorus (directed by Eberhard Friedrich) the grail itself turned out to be a faceted stone, passed from singer to singer, after which everyone hugged as if in a collective trance. Parsifal drops the grail at the end, and we watch it shattering on the stage floor wondering whether it might be better to put our AR glasses back on or not.

Confusion Abounds

Every time I repositioned the glasses to have another look, I was again bombarded with opaque visual debris, some of which—those rotating purple skulls!—actually hid Kundry and Parsifal as they sing each other into new love and compassion. It takes a lot of nerve to purposely cover up important scenes, thereby interfering with any possible enjoyment of the glorious music and powerful singing, in the name of cutting edge technology. Professional singers on the world stage work long and hard to finesse these arduous roles. Yet their efforts were trashed in the name of updating the Bayreuth experience.

Other than the willingness to look cheap and casual, the on-stage message seemed to be that this is a post-religious world, filled with empty rituals and sublime music. Riddled with flaws that could require the entire next year to suture, the disastrous production lacked enough stellar singing to smooth over the disarray. Schager, for example, was more memorable for his self-satisfied curtain calls than for his actual performance. Even the audience on the 23rd of August was amateurish, piercing the production with two cell phone interruptions and daring to applaud before the last, tender, ethereal notes had finished.

No detectable concept or central idea seemed to be involved in the choices made by director Scheib. The performances irritated rather than enthralled, and that’s hard to do with this apex of musical architecture. Even the music itself felt bruised by this as-yet unready mashup.

The AR potential might, someday, be quite exciting. Another time, with thoughtful, even skilled content, it might have added something extra, and extraordinary, to the experience of Wagner’s sacred festival play. This was not that time.

The only saving grace was conductor Pablo Heras-Casado, who gave a deeply felt and comprehensive account of Wagner’s final opera. Especially in his creative use of rubato, allowing the huge tidal pull of the rising chords to hover, poised almost breathless before plunging back into the tempo. Under his baton, the music articulated the Grail quest’s invisible structure and in most cases managed to survive the haphazard stagecraft.