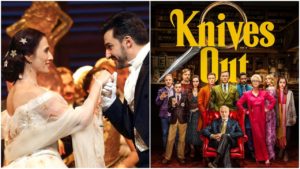

Opera Meets Film: How ‘Knives Out’s’ Use of ‘La Traviata’ Provides More Thematic Depth Than Meets The Eye

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment looks at Rian Johnson’s “Knives Out.”

[MASSIVE SPOILER ALERT]

Director Rian Johnson has recently been expressive of his love and passion for opera. He was very supportive of the Met Opera’s production of “Der Ring des Nibelungen” at the end of the Met Opera’s 2019-20 season and has also been a champion of the company’s own “Aria Code” podcast.

So it wasn’t surprising to see that his latest film, “Knives Out,” found a way to include a fleeting excerpt from one of the greatest operas ever written to go along with what is arguably his best film to date.

Old & Dying

As the film heads toward the end of its second act, detective Benoit Blanc heads over to the one person that he has not spoken to in the entire film – Greatnana, the matriarch of the family and mother to dead Harlan Thrombey. Throughout the film, she has been but a museum piece in the massive house. An artifact of another era that has little to say and can’t really take any action on her own.

So it is no surprise that to match this characteristic, Johnson chooses an art form that some might align with these characteristics in the eyes of his audience. An Anna Netrebko recording of “Ah, fors’è lui,” with a dated vinyl quality, rings out to commence the scene. Johnson provides a closeup of the record player with the music providing little other context until he cuts to a wider shot that reveals Greatnana all alone in front of a window, trapped inside her old age, all supported by the somber tones of Verdi’s famed aria. Blanc himself muses on the nature of aging and this very sense of wisdom and knowledge being trapped. He tells her that he feels she has much to say about the events unfolding. The entire scene is full of nostalgia and the inevitability of death as Blanc offers his condolences to the mother who has lost her son (he is the first to do so in the film). The music’s own emotions seem to hint that Blanc is not going to get anything out of this interaction. It’s a literal dead end.

And sure enough, Grandnana ultimately provides the answer that Blanc needs to connect the dots – Ransom did return the night of the suicide before Marta came back.

But Johnson is constantly feeding the audience information so that they feel comfortable with one interpretation before revealing that there is much more to look for that he originally provides.

And in the same vein as Greatnana has more to say than meets the eye, the excerpt from “La Traviata” also has more to communicate in this story of deception and mystery. In fact, given the context of a detective film, it is no surprise that this excerpt itself provides clues into the film’s overarching themes.

Two Heroines

On the surface, the aria might just be a representation of a dying era. But Violetta, the opera’s protagonist, is in many ways more connected to the film’s main protagonist Marta. The aria itself might not necessarily serve a thematic function outside of its emotional potency within the context of its scene, but this is undeniably one of the most renowned passages from the Verdi opera and it immediately draws an intertextual reading between the opera and the film at large.

First off, Marta and Violetta are women on the margins of their society. Violetta is a courtesan of 18th-century France while Marta is an immigrant in the U.S., her country of origin of no interest to the privileged members of the Thrombey family. Both of these characters are abused by the upper class and their value is determined by their usefulness. Violetta is allowed to party with barons and other people of high repute because she provides them with pleasure. But when she accepts a love given to her freely, that very society, embodied by Germont, sees her as a threat to the social order and tries to crush her. She ultimately chooses to sacrifice herself to ensure that her beloved “Alfredo” gets the right life society has taught her that he deserves. The tragedy of the opera is not that Violetta dies of tuberculosis but that she is killed by a system rigged against her.

Marta, meanwhile, is useful to the Thrombey’s because she takes care of Harlan so that they don’t have to. Harlan does have affection for her because, like Alfredo with Violetta, he sees beyond her function in society and treats her like a human being with feelings. As such, he gives her his inheritance freely and a chance at a better life. But when Marta is revealed to be the heir, the Thrombeys do everything they can to try and stop her. She is no longer useful to them, but instead a plague on their legacy.

Unlike Violetta, Marta ultimately survives this ordeal and is allowed to restructure the social order, as established by the film’s final shot where she holds up a mug that says “My house… my rules…” But Johnson’s masterstroke in all of this is how it connects back to Grandnana. He could have put the opera in any other scene, even as non-diegetic music. But he chose precisely this scene and this moment to connect the two heroines of the film and opera. And she did it through the oldest character in the story – the one who was the least likely to have any impact on the story because of her age. Like Marta, Grandnana is marginalized throughout until she is allowed the opportunity to right the wrongs of the following generation. In “La Traviata,” Germont realizes his mistake but it is ultimately too late.

Grandnana speaks up and ultimately gives Marta an opportunity to take her place as the matriarch of the house and the new social order. Those marginalized unjustly by society are the ones best suited to right those wrongs for one another.

Categories

Opera Meets Film