West Edge Opera 2019 Review: The Threepenny Opera

Exciting Singers Can’t Overcome Muffled Intentions By The Production

By Lois SilversteinWould Brecht have liked it? The effort? Definitely – the range of visual idea, the splicing of moments of fantasy with hard-core, everyday sauciness, and the righteous indignation of the young, the belligerent, i.e., the protest.

Would Weill? The sharp cacophony of instruments injected any hint of romance or nostalgia, with splatter, splash, and crash, the happy-go-lucky life of the rich, famous and comfortable, with I dare, I go, I act. WestEdgeOpera’s production of “The Threepenny Opera” in this summer festival carried out its mission all right, but did it penetrate?

Not really.

What we had was target practice: yesterday, today, always – greed, lust, domination, lying, you know, the litany of human sins, wrought once in John Gay’s “Beggar’s Opera”in the 18thcentury and revised in the 20thby the brilliant Bertold Brecht and Kurt Weill.

But anything else? No.

Missing the Mark

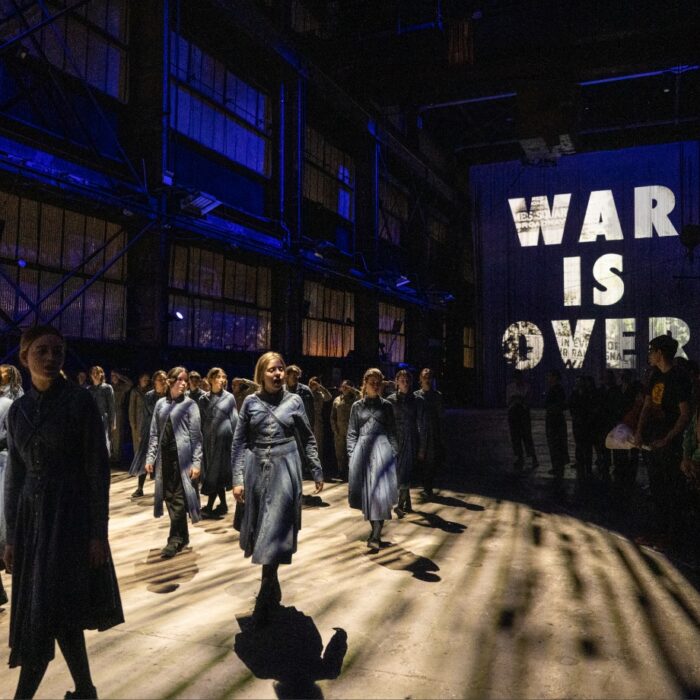

WestEdgeOpera’s production was directed by Elkhanah Pulitizer, set designed by Chad Owens, conducted by David Moschler. The set was static yet animated by a large, metallic-style curtain swung back and forth multiple times throughout Acts one and two. It served to convey change on the surface rather than narrative development.

The same could be said of the central aisle entrance of J.J. Peachum at the outset, the bicycle-riding entrance of Macheath up the ramp onto the stage, and the appearance of marvelous puppet-masked characters in Act one who do nothing more than stand-in for live action. It was an artistic idea, but inflated with only display.

Moschler led the orchestra with clean strokes, crisp sound, and verve. Trumpet and clarinet, accordion and banjo, acoustic guitar, timpani, various saxophones and flute, along with piano, aptly joined together to give us Weill’s inspired score. The ensemble bewitched with the thrum and twang, the whine and the wheeze of the sounds leading and following the story-line zig-zagging through personality and emphatic and witty social critique.

Bewitching Singers

Maya Kherani as Polly Peachum, the waif-style heroine, offered a full-throated and rich soprano display. Plaintive and poignant, she persuaded in almost every aria, showing that she was not only up to the task of reckoning sympathy, she too could bite. Nobody’s fool, Polly, Kherani more than made her point. No classic girl done wrong here; if we expected that, we were happily disavowed.

The same went for Lucy Brown, performed by Erin O’Meally, who was especially notable in her duet with Polly. O’Meally gave an energetic, convincing, and satisfying performance. O’Meally played a good comic foil, pillow-pregnancy and all, and the two energized the last few scenes.

Jenny Diver, performed by Sarah Coit, offered another layer of these, as well as a taste of melancholy, again, sonorous but unsentimental, strong but neither wayward nor affected. Her upper register soared at times – the lower sometimes disappeared into her chest – and her beauty coupled with genuine eros pinged the stage with genuine sensuality. She had something to say, in both words, music and performance: that was a pleasure.

Of course Catherine Cook more than did as well. Her lively, funny, and classy mezzo voice and her acting was a seamless contribution. We were in good hands with her full sound, her vigorous presence and her energy. Dance and sing, scoff and doff, she was a terrific Mrs. Peachum, seemingly without effort.

Other Questionable Players

The “girls” of the Brothel and the streets, more than looked their parts – their costumes terrific – all done by Christine Crook – and their antics. The color alone was stunning.

MacHeath, sung by tenor Derek Chester, also looked the part of London’s lively and vigorous criminal, six pack abs and all, his sometimes sonorous voice over-all ringing out the top notes with robustness, and his flexible movement was a good addition to the stage action. His acting, however, left much to be desired. He was “doing” MacHeath rather than being him. It seemed like impersonation throughout, and while added all the right touches, the acrobatics, the kisses, the devil-may-care-they-love-me-whatever-I -do routine, and kept the scenes going, he wasn’t alluring.

So too Peachum, sung with élan by Jonathan Spencer, but with perhaps too emphatic pomposity – a windbag rather than an appealing Papa; the same went for Tiger Brown, played by Robert Stafford, who was only occasionally convincing as the bleeding heart friend of Mackie. If we kept expecting genuine friendship between these two, we were let down.

The Narrators “barged” in rather than joined the pieces of the plot; perhaps it was the microphone set on extremely high, defied any more connection, though we suspect it was detachment and insufficient attentiveness.

The various “friends” coming and going created more of a small crowd effect rather than the real deal – differentiated characters/types, who engaged rather than entered and exited. These bits not only disappointed but intruded on our sinking into the scenic presentation and surrendering to the situation, which, without sentimentality, was no doubt Brecht and Weill’s intention.

“The Threepenny Opera” not only unfolds, it aims to stick and prick and puncture. It is a wake-up call to all us half-asleep participants in a world wrapped in complacency. It aims for us to act otherwise.

Overall, the performance lacked genuine coherence or connectedness. It was look-see rather than a come and share, care, do something about the way things are. And that disappointed.

West Edge Opera is a genuine group of artists and visionaries, with flair, vitality and wit. They aim to entertain and deliver the goods. It is always something to look forward to, when West Edge Opera is taking on a classic or a new production. The warehouse, setting, like it or not, brims with the real world, the getting to the West Oakland shipyard world a bonus for theatergoers whose best and worst jeans and tee shirts to spend a sunny Sunday afternoon with living creativity. Perfect.

Where the line was between daily life and London, Berlin, the moon – we could never draw. It was a shame because it muffled intention.