Vienna State Opera 2017-18 Review – Ariodante: Sir David McVicar’s sumptuous staging for the Wiener Staatsoper Is a Case of Handel With Care

By Jonathan SutherlandAn alien orchestra playing in the illustrious Wiener Staatsoper is about as rare as a running of the bulls on the Ringstrasse.

Apart from a one-night swap with the La Scala orchestra in 2011, in recent years only Les Musiciens du Louvre, Les Talens Lyriques, and the Freiburger Barockorchester have been granted such a privilege. The latest member of this exclusive club is another consummate baroque ensemble, Les Arts Florissants.

The common factor in almost all these guest appearances is the music of Georg Friedrich Händel. Considering the German-born, anglicized baroque master wrote more than 40 operas, the five in the Staatsoper’s current repertoire certainly leave room for many more discoveries. Given the rapturous reception accorded to “Ariodante” and almost simultaneously, the oratorio “Saul” at the Theater an der Wien, Handel could well become as ubiquitous in Stadt Habsburg as Sacher torte.

After more than 200 years in the operatic wilderness, “Ariodante” recently leapt out of oblivion to become the Handel opera du jour with new productions in Glasgow, Amsterdam, Stuttgart, and Salzburg, and outstanding concert performances by Alice Coote and Henry Bicket with the English Consort at the Barbican, the Theater an der Wien, and Hamburg’s capacious Elbphilharmonie.

An International Opera

“Ariodante” is inherently international. Written in Italian by a native German, first performed in London and set in Scotland, this was 18th century musical ecumenicalism at its zenith. Appropriately for the Staatsoper production, five nationalities were represented in the seven principal roles, with American-born William Christie on the podium for good measure.

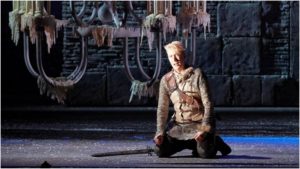

Celebrated Scots director Sir David McVicar is no stranger to the Haus am Ring, but his previous productions of “Falstaff”, “Tristan und Isolde” and “Adriana Lecouvreur” were obviously not part of the baroque canon for which he is particularly acclaimed. Typically, McVicar’s stage pictures were gorgeous to look at with a huge sea and sky scrim behind simple but effective high stone walls which shifted to form various scenes. McVicar took certain pardonable liberties with several specific locations, and the “delightful valley” was populated by preening courtiers instead of picnic-ing peasants. The Great Hall in the final scene became a boozy beachfront barbeque. The “royal gardens” similarly suffered from terminal pruning, but the massive bookcases in the gallery of the palace were splendid indeed, albeit closer to Stuart sumptuousness than Antonio Salvi’s assimilation of “Orlando Furioso.”

Vicki Mortimer’s stage designs provided a stylish background for her opulent 18th century silk, satin, and velvet brocade costumes. Plumed hats and thigh-hugging britches prevailed and the whole mise-en-scène looked like a Hogarthian tableau vivant. The Hibernian milieu was craftily represented by some Gray plaid tartans, the odd highland fling and an enormous dead deer which was later roasted on a spit to celebrate the happy ending. Perhaps not so happy for the stag. The only quirky accessory was the diadem worn by the King of Scotland which was so enormous it made the Imperial State Crown look like an inconsequential bauble.

Handel had not incorporated ballet into his operas before “Ariodante” and Christie restored almost all the dance music which was written for the Pavlova of the period, Marie Sallé. Colm Seery’s choreography was consistently diverting, inventive and whimsical. The simulated drunkenness of the courtiers during the concluding Gavotte/Rondeau/Bourrée was particularly amusing. Even more memorable was the ballet of Good and Bad Dreams as Ginevra watched a mannequin double of herself shamed and violated by malevolent accusers.

Finest Singers Around

When Handel wrote “Ariodante” in 1735 he had the finest singers of the age at his disposal including the pulchritudinous Anna Maria Strada as Ginevra, acclaimed soprano Cecilia Young as Dalinda and the Farinelli-esque castrato Giovanni Carestini for the title role. Reputedly Carestini tossed off the pyrotechnic roulades and leaps in “Dopo notte” with the insouciance of a jaunty jingle.

Benedikt Kobel sang the bearer of bad news Odoardo sympathetically enough but was generally undistinguished. The King of Scotland was performed by Wilhelm Schwinghammer who seemed a tad too young for a venerable monarch with a grown-up daughter. Vocally “Voli colla sua tromba” was full of semi-quaver bass bravura and plumy low E flats and F naturals and Schwinghammer’s palpable despair in “Invida sorte avara” was moving. Rainer Trost was an adequate Lurcanio but with limited stage presence and less than ideal baroque vocal technique. A light tenor di grazie, his natural repertoire is more Mozart than Merula. The fast fioratura in “Il tuo sangue” was managed with accuracy if not Handelian elegance. “Del mio sol vezzosi rai” required more precise diction although the sustained D naturals were solid. “Tu vivi” was earnestly sung but lacked finesse in the agitato roulades.

The Heavy Weights

It’s easy to spot the bad guy in this opera, and Christophe Dumaux scored a singular triumph as the Machiavellian malefactor Polinesso. There was Don Giovanni-ish carnality with the power-hungry seducer groping a maid in Ginevra’s boudoir and his overt sexuality with the gullible Dalinda was entirely credible. From his first unctuous “Ginevra” it was clear this was no knight in shining armor. Caressing Ginevra’s bare shoulders with a horsewhip suggested a touch of S&M was also part of Polinesso’s D&A. Despite its jaunty rhythm, “Spero per voi” was more cynical than seductive, notwithstanding the trills. The French countertenor’s quaver roulades and ornamentations in “Coperta la frode” were as strong in the upper range as in the impressive low chest notes and “Se l’inganno” was a study in musical malice.

As Polinesso’s easily duped accomplice who is later racked with genuine remorse, Dalinda is not exactly a mono-dimensional bimbette. Handel’s music for this confused character has some of the most lyrical writing in the score and Staatsoper ensemble member Hila Fahima excelled in the role. This is a soprano who has the Königin der Nacht in her repertoire, but the voice also has the pellucid lyricism for Pamina. “Apri le luci” with its high tessitura was plaintive with a crystalline timbre. The peppy “Il primo ardor” displayed fine agility in the runs with some scintillating top B flats. It was easy to understand why Lurcanio would forgive her blatant infidelity.

The role of Ginevra is arguably the most demanding in the opera, especially as the range of emotions and corresponding vocal line is so extreme. The vain frippery in “Vezze, lusinghe” and disdainful “Orrida a gl’occhi miei” established at the outset that this is a princess who feels no oblige to her noblesse. The psychological collapse after Lurcanio’s false accusation of sexual impropriety gave “Il mio crudel martoro” an abject pathos. Ginevra’s eventual euphoric rehabilitation requires refulgent articulation in “Bramo aver mille vite” and Israeli soprano Chen Reiss more than satisfied all these dramatic and vocal demands. The rapid semi-quaver roulades and top B flats in “Volate, amori” were exact and effortless. The unusual “Che vidi?” accompanied recitative ending to Act two had Handel’s desired dramatic impact. Consistently limpid intonation, clean trilling and intelligent word colouring made Reiss’ performance one to savour. Only the lilting 3/8 “Prendi, prendi da questa mano” duet with Ariodante and cello obbligato lacked her usual lustrous legato.

The Big One

Like Armida or Alcina, the title role in “Ariodante” is no baroque bagatelle. Sarah Connolly is an indisputably accomplished singer in many different genres, but there was something missing in this performance. Admittedly all the notes were there and the low chest voice D naturals and E flats in a slightly sluggish “Scherza infida” had punch but the middle range fioratura lost projection, if not focus. The measured legato phrases in “Qui d’amor” were more successful than the slightly fuzzy roulades in “Con l’ali di costanza” and “Dopo notte.” There was also a slight dramatic detachment. For some reason, McVicar’s Ariodante doesn’t do a Senta-like leap off a cliff after “Scherza infida,” but ambles into the briny only to roll back again in Act three like a piece of mail-suited flotsam.

Les Arts Florissants & Beyond

The chorus of the Gustav Mahler Chor acquitted themselves with distinction and there was some commendably engaged and puissant singing in the rollicking “Sa trionfar ognor virtute in ogni cor” finale. Individual characterizations made this fine choir even more interesting.

William Christie and Les Arts Florissants rocketed to fame in 1987 in a now legendary production of Lully’s long forgotten “Atys” for the Opéra Comique in Paris and never looked back. On this occasion, the esteemed ensemble’s maestro and muse led the performance with precision, pathos and pétillant panache. Christie’s tempi were more measured than precipitant but there was still plenty of fire. This was a welcome change to recent interpretations by other soi-disant baroque experts where every allegretto is turned into presto. There was some outstanding woodwind and brass playing and the baroque bassoon obbligato in “Scherza infida” gave an oboe-ish melancholic timbre to the exquisite aria. The string accompaniment to “Dopo notte” was particularly potent with acerbic down-bowing and pristine trills and the introduction to “Quì d’amor nel suo linguaggio” gracious and grand. The gifted musicians based in Caen have a particular penchant for early French music and relished the lengthy instrumental ballet passages. There was both lilt and lyricism to match the crisply articulated marcato indications.

The combination of an inspired regisseur with outstanding musicians and accomplished singers made for a triumphant return of baroque opera to a house which does not normally resound with roulades and ripieni. Perhaps Pamplona in the Prater is not so impossible after all.