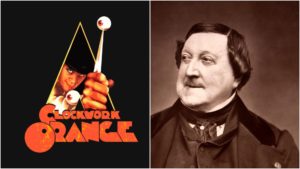

Opera Meets Film: Watch & Experience the Dark Truth Behind Stanley Kubrick’s Use of Rossini In ‘A Clockwork Orange’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment is Stanley Kubrick’s legendary “A Clockwork Orange.”

Stanley Kubrick was a genius and his dozen or so films bear this out. While this may be but the first time we take a peek at one of his movies, it is unlikely to be his last.

“A Clockwork Orange” is a ruthless look at violence and aggression in a young man. As the film opens, Alex, our protagonist and narrator, shows us a typical day with his gang of friends as they engage in acts of violence against a drunk old man in the streets, another gang, and unsuspecting people at home. Eventually, they attack one another and at the climax of the film’s first act, Alex’s reign as the leader of the gang comes to an end when he is arrested.

The film employs a ton of classical music, as was Kubrick’s wont, though most people would associate the film’s soundtrack with Beethoven’s ninth symphony, which Alex notes is his favorite piece. It plays a major part in the story, though interestingly, the composer to feature most prominently in the film is none other than Gioachino Rossini.

Two prominent pieces of Rossini’s appear throughout the film – the overture to “Guillaume Tell” and “La Gazza Ladra.” The first appears when Alex engages in a threesome in his room and later when he is taken to prison and when he returns home before attempting suicide.

“La Gazza Ladra’s” overture appears when Alex and his gang engage in acts of utter violence.

Think about Rossini for a second. What do you associate with him? Comedy. Fun. Sparkling wine. Bubbling energy. Likely not the aforementioned scenes.

But this is exactly why he functions as the perfect composer to complement Alex’s journey from violent teen to “reformed” human being.

Let’s take the sex scene with the sped-up “Guillaume Tell Overture.” (Beware of Nudity in the video below).

While the music undeniably adds to the energetic portrayal of the scene (in a sped-up framerate), it also makes it comical. We all know the piece and its associations, so to see it employed in this fashion adds to the satirical nature embedded in the film.

But the use of “Gazza Ladra” furthers this point even more. It’s a pleasant piece of music that, unlike the “Guillaume Tell” with its electrical adaptation by Wendy Carlos, is used in its original orchestral sound. Listening to the piece is engaging, fun, and catchy. Try listening to it and walk away forgetting it right away. Chances are, you won’t.

And that’s the whole point. The film ends with Alex conditioned to associate Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with violence, thus making it impossible for him to listen to his favorite piece ever again. Kubrick kind of plays a similar trick on the audience.

He underscores Alex’s reign of violence with Rossini’s great overture, lending it a strong counterpoint that expresses his satirical purpose in the content of the film. But he also makes the audience enjoy it. Just watch.

There are some disturbing moments in those two differing scenes. And while we consciously know how horrible these scenes are, Rossini’s music somewhat dulls the blunt nature of the violence. We don’t see Alex as a monster, but a product of his environment. We like him because the music contextualizes him in a charming manner. We want to keep listening, just as Alex wants to keep on with his violence.

And it is in this dark manner that Kubrick makes us unwitting accomplices in this violence. He is pointing a finger at all of us and reminding us of our own violent potential and enjoyment of it.