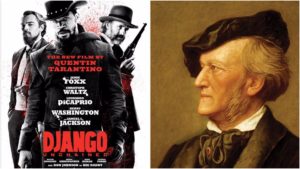

Opera Meets Film: How Quentin Tarantino’s ‘Django Unchained’ Is Inspired By Wagner’s ‘Siegfried’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Quentin Tarantino’s “Django Unchained (2012).”

At first glance, one might look at the title of this piece and say – what does a Civil War spaghetti Western about slavery by an American filmmaker have anything to do with a mythological German opera by one of the art form’s great intellectual masters?

Everything.

In fact, Tarantino is said to have been inspired, in part, by a visit to the opera alongside actor Christoph Waltz. The work they saw? “Siegfried.”

The opera itself makes an appearance at one point with Waltz’s character Dr. Schultz relating the myth to the protagonist Django.

The Characters

But the similarities don’t end there. Django is ultimately Siegfried’s surrogate in the opera, growing from a speechless slave, much like the inexperienced and brutish Siegfried of the opera, into a polished hero that slays his own dragon and saves the love of his life.

The dragon in the film is Candie, the plantation owner played by Leonardo DiCaprio, who hoards his wealth much in the same way that Fafner has a hold on the Ring and other possessions. Like the dragon, he gets killed off two-thirds of the way through the work.

Schultz is a mentor to Django, who is morally ambiguous, much like Mime is to Siegfried. Both characters use the protagonist to further their own agendas. In the case of Mime, he wants Siegfried to reforge the sword to help him get the Ring that will fill his material desires while Schultz wants Django to help him in his activities as a hitman to earn a big bounty. Again, both characters are killed off about two-thirds of the way through their corresponding works.

Tarantino is rather explicit in the name he gives to the wife of Django, Broomhilda von Schaft. When we first encounter her, she is sleeping in a “hot box,” which undoubtedly is a direct correlation to Siegfried finding Brünhilde on the mountain surrounded by fire. She is often portrayed as sleeping throughout the film as well, a callback to Brünhilde’s initial state for much of the opera.

Crumbling Institutions

One major difference that might pop out to opera lovers is the absence of a Wotan character in “Django.” On the surface, that can be justified by one major reason. Wotan’s story is a continuation from previous operas, a narrative that continues into one more opera. “Django” does not have that responsibility of carrying over the mythology of other movies and hence can easily do away with the Wotan character without major cost to the work.

But Wotan does exist in a different way in the film. Being the God that governs all through his deal-making spear, establishing a firm and often contradictory and oppressive society around him. We see this in “Die Walküre” where he suffers the death of his own son due to being bound to contracts he instituted. He is, as Wagner makes it plain in the final opera of the quartet, a crumbling institution of Gods that are no longer fit to rule the modern world of the myth. Wagner, of course, was in constant contact with Fredrich Nietzche, who famously wrote “God is Dead” and decried religious institutions.

In the third act of the “Siegfried,” Wotan and Siegfried lock horns with the former impeding the latter from accessing the mountain where Brünhilde sleeps. But Siegfried dispatches the older God with the sword Nothung, making swift work of him and setting the stage for Wotan to burn in Valhalla by the end of the next work, aptly named “Götterdämmerung (The Twilight of the Gods).”

Tarantino’s Wotan is the institution of slavery itself. Oppressive, contradictory, as explored in the character of Stephen (a slave who oppresses other slaves, played by Samuel L. Jackson), and ultimately out of step with the times, Tarantino uses his film to destroy the institution, much in the way Wagner’s tetralogy does.

As the film draws to an end, Django burns the plantation Candieland, the ultimate symbol of cruel slavery of that era, to the ground. Much like Wotan by the end of “Ring,” slavery will face a similar rude awakening, burned to the ground during the forthcoming Civil War.

***I am aware that the film uses an excerpt from Verdi’s “Requiem,” though I plan to explore that in a later installment. Wagner’s music fails to appear anywhere in this film.