Mostly Mozart Festival 2019 Review: The Magic Flute

Suzanne Andrade & Barrie Kosky’s Production Is A Wonder To Behold

By David Salazar(Credit: Iko Freese)

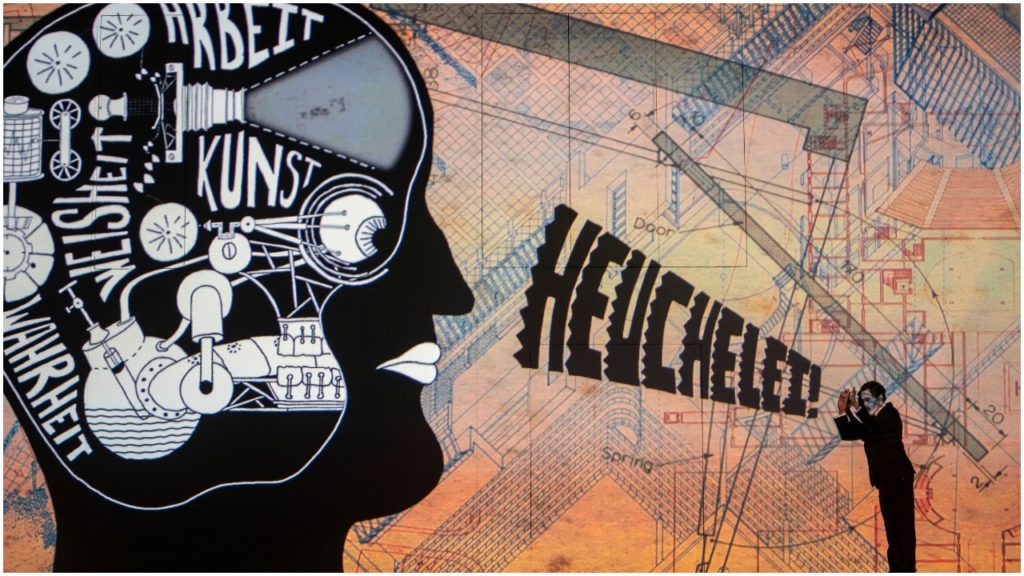

After a big red curtain opens up at the end of the overture, the audience is greeted with a massive movie screen. In the center, a door rotates to reveal Tamino behind an extension of the screen that covered the lower part of his body. Suddenly the projections came alive with the chase of the beast underway. The lower part of Tamino’s body projected running legs while the backdrop a crop of fields reminiscent of the famed helicopter scene in “North By Northwest.” The audience exploded in laughter at the entire scenario which brought the action of this scene to vivid and comic life.

This energy and creativity permeated Suzanne Andrade and Barrie Kosky’s “The Magic Flute” during the performance at the David H. Koch Theater on July 19, 2019. And to be honest it is one of the most fascinating operatic experiences that one can have.

The overall experience is akin to that of a silent film, albeit with lots of color and perfect comedic timing. In the ensuing scene, we are inside the stomach of the beast where the three ladies (now given names) each attempt to revive Tamino by blowing him kisses of hearts (real-looking ones) and compete digitally over his potential affections.

Papageno has a cat friend that follows him everywhere and creates a number of incredible visual gags that hit the audience’s collective funny bone each and every time (at one point, the cat faces off against Monostatos’ hounds).

The flute and glockenspiel are visually personified, giving them a greater bandwidth as to how they can impact the world around them. One character sings inside a snowglobe and we even get some video game jokes thrown in there for comic relief.

Here’s a trailer where you can get a glimpse of the visual splendor.

A World In Transition

But the visual gags aren’t just limited to visual jokes or simply technological marvels; Kosky and Andrade manage to tell a compelling fairytale through the technology that showcases the Queen of the Night’s realm as a damaged natural world with Sarastro’s being the world of technological advancement. The Queen is depicted as a large spider that towers over Tamino in their first encounter and does the same with Pamina in their big showdown. She tortures both of them, essentially dismissing the opera’s plot twist that she’s the big bad of the story. But having her as THE potent predator in a magical animal kingdom allows the directors to contrast, but also bring together the similarities with Sarastro’s own realm. For in this context, the Queen’s motives are not to kill Sarastro over religious or spiritual ideology, but as a biological instinct; she’s technically not evil, but trying to protect her world.

We see animals turned into machines with an entire sequence dedicated to watching live chickens unfeathered, roasted, and served up as a dish for Papageno. Humans are run through machines and injected with attributes that pop up on the screen. Sarastro’s world of technological advancement is inevitable, but the production puts it cautionary aspects on full display, suggesting that the heroes of the tale have in some ways been brainwashed into accepting this new way of life.

Of course, as Tamino underwent the trials and passed some of the tests, the 2D world seemed to take on greater dimensions with a crowd of men surrounding Pamina at one point. When Tamino managed to pass all trials, the initial red curtain came back down and the chorus took the stage in front of it, eventually climaxing in a moment where Pamina and Tamino enjoy their first kiss; they were all freed from the artifice and allowed to enjoy life in full dimensions.

It’s also worth mentioning that despite their “limited” movements, the actors are tasked with interacting with a digital environment that is behind them and in two dimensions; the timing and awareness that this requires is undeniably no easy feat as any misstep would bring the artifice of the entire world being created to light and throw the audience out of the experience. The fact that it was pulled off to near perfection emphasizes how well-conceived and directed this entire venture was.

(Credit: Stephanie Berger)

Changing The Script

In Kosky fashion, the dialogue of the original Singspiel has been done away with. Instead, in typical silent movie style, audiences get intertitles with the essential bits, allowing for a more streamlined narrative experience that gets the audience from musical number to musical number with minimal interruption. Kosky employed a similar narrative approach with his “Carmen,” eschewing dialogues and recitatives for voiceover narration, thus allowing his conception of the piece more as cabaret than opera to come to the fore. It didn’t quite work for “Carmen,” but the results are quite effective and cohesive in “Flute,” mainly because the audience’s attention remains onscreen the entire time; we feel like we are, in effect, watching a strange cinematic alchemy that might have been produced right in Sarastro’s laboratory.

The lack of dialogues does ultimately diminish the characters themselves, much as was the case in Kosky’s “Carmen.” The interactions are limited to stock poses and gestures that generally elicit laughter. But our attention as viewers moves to the words that appear onscreen anyway so the actors are pretty much an afterthought. We wind up formulating our understanding of the characters through how we interpret the text, not how the actors react to one another. In the larger framework, the actors become mere puppets for the drama, the story imposed on the viewer by the technology.

This style of storytelling, with the presence of the director/auteur looming large in every moment didn’t quite work for a human drama like “Carmen” where the emotional neutering made the entire opera void of emotional investment, but definitely manages to engage in a more archetypal fairytale like “The Magic Flute.” If anything, the technology’s power speaks quite openly to the opera’s themes themselves, as presented here, adding to the sense that the sum of the parts is a truly mesmerizing whole.

Perfect Casting

As noted, the singers themselves deserve tremendous credit for the way they make the entire artifice feel alive at every moment, even if their work comes off as more technical than vivid and life-like. But it does place a special emphasis on the musical numbers and the impact they can have.

Tenor Julien Behr as Tamino, managed an even tone quality throughout the night, coupled with a true vocal presence that made him the opera’s hero. “Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön” is a very challenging piece for any tenor, opening on an interval jump from a B flat to a G natural right in the tenor’s passaggio. But Behr displayed tremendous confidence with this opening line and the similar vocal jumps that followed, always creating a sense of unified line and a sense of forward movement and emotional yearning that characterized Tamino’s newfound love. At the climax of the piece, with several ascensions to high A flat, his voice grew in strength as he delivered each high note with greater intensity, but never any sign of strai n.

The second aria, “O wenn ich doch” was probably even more impressive, with the tenor opening on the most delicate of vocal enunciations, his voice growing into even more intense vocal outbursts (as he lamented the potential loss of Pamina) than anything he had showcased in “Dies Bildnis.” His singing then took on a brightness particularly in the ending “Vielleicht führt mich der Tonzu ihr.” It was full of tremendous range that allowed us to feel Tamino’s initial heartbreak, desperation, and eventually fulfillment and joy.

As Papageno, Rodion Pogossov’s clear and vibrant baritone also took centerstage every moment he was on. “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja” had a jubilant quality to it, the baritone simply allowing the fullness of his voice to carry the charming tune. In many ways, he was the comic scene-stealer of the entire production, but this was undeniably by design, particularly in his interactions with the digital cat he was given. This alone, allowed the character to gain a tremendous amount of emotional connection with the audience. And yet, for all the fun he managed to give the audience, he really shone in the dark “Nun wohl-an,” the voice taking on a darker quality with a hint of desperation that turned to bitterness on the final accented “Gute Nacht, du falsche Welt!” The transition to this darker moment was made all the more potent by the preceding enunciations of Eins, Zwei, Drei, with its long pauses and Pogossov’s own visual expressions and body language expressing a deep sense of increasing loss and disappointment.

This all made that final duet with Tayla Lieberman’s Pappagena pay off that much better with the two in perfect vocal harmony as the digital imagery around them depicted their homes and dozens and dozens of Pappagenos and Pappagenas; the audience was hysterical throughout this duet.

(Credit: Stephanie Berger)

Soprano Maureen McKay’s first vocal enunciations as Pamina displayed a hard-edged sound, but it suited the situation quite perfectly; Pamina is a prisoner, being menaced by three massive dogs on a leash held by Monostatos.

But as she eased into the opera, her voice took on a lighter complexion, which blossomed in the glorious “Ach, ich fühl’s” where Pamina is locked up in what looked like a snowglobe, lamenting the loss of her lover. Here McKay’s voice soared beautifully, particularly in the G natural that opens the second phrase “Ewig hinder Liebe Glück,” which she plucked out of the air without any seeming difficulty (a lot of sopranos struggle here and with ensuing phrases that open in the passaggio). The runs to the high B flat were delivered with ease and a great sense of connectivity, all of it adding to an increasing sense of torment and pain. She gradually dimmed her voice in the aria’s latter sections, delivering a floating high B flat on “Liebe Sehen” followed by a subtle crescendo on a G natural on “Ruhim.” The entire aria was an incredible display of vocal artistry and emotional depth.

Guiding Spirits

As the Queen of the Night, soprano Audrey Luna, who stepped in at last second for an ailing Christina Poulitsi, managed some tremendous applause all around and there is no doubt that her voice resonated quite potently throughout the hall in her two show-stopping arias. And while the high F naturals were well-placed and crystal clear and her phrasing was pointed and precise, her pitch in the upper regions of her voice frayed in both arias “O zitt’re nicht” and “Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen.” The coloratura runs were also sloppy in the first aria. Still, she was an imposing presence as the Queen, making the most of her brief appearances to make a lasting impact on the narrative.

As Sarastro, bass Dmitriy Ivashchenko displayed a warm and elegant bass sound at the start of “O Isis und Osiris” and “In diesen heil’gen Hallen,” emanating a sense of peace and gentility. Still, his Sarastro is an ambivalent figure in this production and there was a coolness in the bass’ singing overall; it worked within the interpretation and allowed the roundness of his middle and upper register to ring gloriously into the hall. Unfortunately, his lower range was barely audible in the hall and would often be covered up by the slightest of crescendos in the orchestra. One might blame the Koch Theater for its well-known limitations in the acoustics department, but the singers came through quite clearly and consistently throughout the evening.

(Credit: Stephanie Berger)

As the Three Ladies, Ashley Milanese, Karolina Gumos, and Ezgi Kutlu had a blast and it showed not only with their own physical antics (they arguably got the most to do physically), but also in how they managed to join their voices together seamlessly.

As Monostatos, tenor Johannes Dunz looked like Boris Karloff wearing a Megamind costume and he really played up the opportunities to be a lecherous monster. In arguably the most chilling scene of the production, we see Pamina in bed sleeping while Monostatos rises up from under the blankets to sing “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden.” The relish and brightness that he gave his merry tune only added to the overall sense of danger one felt for the unknowing Pamina. It was creepy and tense, especially with his every move toward her accompanied by black hands closing in on her. At the close, he jumped back under the sheets, adding to the darkness of the moment.

The chorus of the Komische Oper Berlin and Tölzer Boys Choir was excellent throughout the night, as was the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra, which breezed through the score with great energy and precision. Much credit must be given to maestro Louis Langrée who had to conduct the opera with the technology very much on his mind; any misstep could potentially bring down the entire show, but in his hands there was a sense of security. Of course, it meant that the music-making didn’t exhibit a great deal of risk-taking or even a great sense of flexibility with tempi, but it didn’t detract in any way from the performance.

Purists might be turned off that the opera, despite being sung in “German” didn’t have the full dialogues to accompany it. But there can be no doubt that this production is a true creative achievement that immerses the audience in the world of the story in a way that other productions simply can’t. There is a lot going on visually and yet there is never a sense of sensory overload or even a sense that some of the imagery is trying to fill creative gaps. It’s a wondrous conception that any opera house would be lucky to present to its audience.