Metropolitan Opera 2018-19 Review: Samson et Dalila

Roberto Alagna & Elina Garanca Struggle Through Disappointing Production on Opening Night

By David SalazarOver the last few weeks, the Metropolitan Opera has hit one home run after another with news of a more accessible schedule structure as well as support for newer operas in new locations over coming seasons.

These major stories have emphasized a new era, so to speak, for the company, and the organization has even baptized that progress with a new marketing slogan, “Drama in every breath.”

But as they say, “the more things change, the more they stay the same.” At least this was the big takeaway on Monday, Sept. 25, 2018, with the company’s new production of “Samson et Dalila.”

Of course, nothing was going to change overnight and even a progressive master like Yannick Nézet-Séguin can’t get general manager Peter Gelb to suddenly start putting together a clearer strategy for how to tackle his new productions.

As has become an increasing motif of the Gelb era, the message seems to be that new productions exist to provide a fresh coat of paint on older ones. It doesn’t seem to be about creating a new aesthetic or thematic style for a new audience, but simply to put on a newer flashier piece of clothing or a more colorful set. It’s all style with little to no substance.

And this was at the core of Darko Tresnjak’s new production of the French opera on opening night.

Style Over Substance

Entering the theater, one was immediately struck by the semicircular curtain dominating the stage. Handprints permeated the image, emphasizing the enslaved Jewish community and one got the sense of something that could be both raw, but with a hint of poppy color. Once the curtain came up at the start of the opera, Tresnjak and set designer Alexander Dodge (both in their Met debuts) made a bold design to leave part of the curtain down, the metallic pattern expressing this sense of imprisonment that suited the opera’s opening passages. Two large towers and a central stairway allowed for a visual exploration of the society of the story. The people of Israel, clad in grey, stood at the bottom of the staircase as the Philistines, wearing gold, stood above them. As an opening image, it was strong and to the point. But it never progressed and the production’s major issues would manifest themselves ever so slowly from here on out.

The second act takes place in Dalila’s home. Again, there is a staircase and what seems to be a large mirror on stage right; what the mirror is doing exactly is beyond me as the characters barely interact with it and its massive size seems to warrant more importance than it deserves. There is a firepit in the center to create ambience that unfortunately never comes. Act three is undeniably the most impressive of the sets, the first scene taking place in a cramped cell where Samson pushes the mill wheel. There is an awkward transition to the great temple, but the reveal is quite epic and the applause indicated that the audience was undeniably stunned. A massive statue of what one presumes is the god Dagon (though he distractingly looks like Dr. Manhattan of “Watchmen” when the lighting turns him blue and his eyes pure white) stands tall at the center of the stage amongst a sea of red and gold; he is split in half to allow space for characters and dancers to enter to and fro. The wardrobe by Linda Cho, also in her Met debut, is also quite impressive with those of Dalila oozing with sensuality and luxury.

On the whole, the production looks impressive. But there is one major issue that makes it all seem so in vain – the stage direction. And because of this, there wasn’t “drama in every breath.”

No Payoff

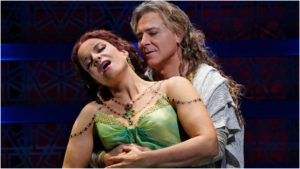

Tresnjak’s most bewildering achievement with this production is that he makes two incredible actors like Elīna Garanča and Roberto Alagna look lost on stage and lacking in utter chemistry. Their first confrontation in Act one is all about flirtation and Dalila’s progressive control over him. But it is all static and weightless. They glance at each other a few times, she takes his hand at another. She ignores him a bunch. He looks over at her confused. But their interactions don’t really express or suggest much in the way of interest; it doesn’t build to anything. The stock gestures and robotic nature of the staging took me out of the moment and at one point it felt like the Serbian director had popped in the DVD of these two great artists in “Carmen” and asked them to replicate their performance from the first Act where the titular heroine starts insinuating herself to Don José in front of the other women and soldiers before his duet with Micaëla.

Things didn’t improve in Act two, the chemistry between the singers slightly stronger, but there were major questions about intention and characterization, especially of Dalila,that didn’t allow anything to build or develop in a cohesive manner. The seduction of Samson was rather bland, Dalila pulling off one layer of clothing, then standing over him, before they eventually lay together. The crackling fire suggested something sexy and hot on the way, but it never got there. When Dalila demands that Samson reveal his power, why not continue in that direction? Dalila talks of using her power and sway over Samson, but she just stands over him like a mother scolding her child. Her POWER over him is clearly of the sexual variety, so why doesn’t Tresnjak explore this further instead of having his characters revert to standing around and looking lost onstage?

Act three fares best, though the final moment where Samson “destroys” the temple is anti-climax at its best. With the massive Dr. Manhattan / Dagon statue standing so potently, one would imagine that the fall of the temple is related to it in some way. Samson destroys the chains, everyone stands around, some lights flash in the background and… The End. Nothing. No coup de théâter. We are all left waiting for something richer to end our experience. It never comes. Maybe you could blame the audience here for establishing high expectations, but everyone knows what’s coming; the set-up is in the opera itself. Moreover, Tresnjak plays the audience by having Samson exiting upstage, seemingly leaving the space and creating anticipation that he might be heading elsewhere to set up that final moment. When he finally reappears from where he left, it is clear that this stage direction was unnecessary and ultimately a red herring for the viewer. And the ensuing lack of payoff is all the more disappointing.

The choreography is a hit or miss with the Act one dance of the Philistine maidens erotic but sloppy and the Bacchanal more entertaining though never quite managing the sensual heights of the previous production by Elijah Moshinsky. The fight choreography in Act one, wherein Samson kills Abimélech, was also robotic. It makes you wonder what the point of all these new productions ultimately is if they bring little new to the stage.

Of course, the answer lies in the singers. These new productions at the end of the day are all about providing vehicles for the stars. But none were shining all that brightly.

Cool, Aloof & Confused

Elīna Garanča’s last performances at the Met were of the scene-stealing variety; her Octavian in “Der Rosenkavalier” remains one of the best displays of vocal acting over the last decade. To have her return to open a season was certainly an exciting proposition, but in some ways, she put on the most frustrating display of the evening. She took considerable time to vocally warm up into the role, her sound pure but rather small in the opening Act. Moreover, her French pronunciation often lacked clarity in this opening portion. She was noticeably better by the time the second Act, HER act, came around, the sound opulent and powerful, especially during the opening passage “Samson, recherchant ma presence.” Here her sound filled the theater in waves, generating great excitement. Her duet with the Grand Priest continued in this vein, the sound forceful and intense in its directness (she also threw off a coloratura passage with insane confidence and security out of nowhere). And the duet with Samson climaxed with the famed “Mon coeur s’ouvre à ta voix,” Garanča’s timbre oozing with sensuality, the phrasing gentle and yet building in waves. The ebb and flow of her phrasing was seductive to be sure and you could feel that for the first time, she really had complete control of everyone’s attention in the entire theater. The building phrases of “responds a ma tendresse” surged with energy, keeping us under her spell, tempting us emotionally. It was the undeniable high point of Garanča’s performance, the hit number’s transcendence coming alive.

But unfortunately, it all came packaged with what seemed to be an unfinished characterization. Who Dalila was or what she felt remained a mystery throughout the night, though that didn’t seem to be the intention. Did she feel anything for Samson? We’ll never really know. There were suggestions at different junctures that she might feel guilty over betraying him, but they were nothing more than suggestions. At one point, as he opens his heart to her, she turned away from him, rested her head in her hands and looked away. Was she feeling guilty? Bored? Annoyed? It came so suddenly and without any setup, that we don’t know what it meant. Earlier she seemed afraid of something as the Grand Priest walked out, but again, we didn’t know exactly what she might be afraid of. Hurting Samson? The priest’s wrath? In the final act, she seemed to be upset at the treatment of Samson, but it was hard to really empathize with her position when there really hadn’t shown much proof beforehand that she has any such noble feelings. What it did was ultimately make Garanča’s overall interpretation seem cold and distant, perhaps even disconnected. Her Carmen was undeniably cool and collected, but within the production and her interpretation, we understood her coldness to be a defensive mechanism against an inconsiderate and chauvinistic world. Here, Dalila’s coldness rips dramatic potential away from the opera. We don’t feel much of anything for Dalila, which makes it so easy to dismiss her character. It makes it all about Samson’s goodness and the evil seductress who took away his pride and morality; there’s nothing progressive in that reading. One could claim that the libretto has its own limitations in this regard (and you wouldn’t be wrong), but there are other interpretations by arguably lesser actresses than Garanča that show us that Dalila as a three-dimensional character is certainly not out of the realm of possibility. The overall characterization (or lack thereof) just didn’t feel like Garanča at all. This I lay at Tresnjak’s feet.

A Hero Battling His Voice

Roberto Alagna was far better in terms of his characterization of Samson of a fallen hero who finds redemption. He was best in the second Act where Samson’s tortured soul and indecision comes to the fore and the implied sense of paralysis fit well with the dramatic context. And in Act three, he was definitely the broken man one would come to expect.

Vocally, however, it wasn’t his night. His way with the text was always clear and decisive, but his sound showed increasing wear and tear over the course of the evening. He doesn’t possess beauty of tone, especially in the upper range, but Alagna has a knack for making his instrument work to his needs. He’s as expressive as they come and even if the aesthetic beauty of his sound doesn’t get you, his expression certainly will. And for one act and change, he sounded great. His opening entrances “Arrêtez, ô mon frères,” had clarity and directness that emphasized Samson’s stance as a potent hero. And for the better part of an hour of music, Alagna maintained this level of vocal stability. every challenge Saint-Saëns threw at him was no challenge at all for the French tenor. Then came Garanča’s big moment and he started to fade. His cries of “Dalila je t’aime” in response to her seductive “Mon Coeur s’ouvre à ta voix” sounded rather faint, the end of the phrase chopped off. The placement of phrase is certainly not easy for the tenor, but here it sounded like Alagna’s sound was losing clarity and vibrancy. The reprise of the main theme of the aria, with tenor accompaniment, saw Alagna struggle for accuracy of pitch and the climactic B flat to end the duet was strained, the tenor pushing with extra effort to get the right pitch.

Things didn’t get much better in Act three as Alagna’s ascension into the passaggio and beyond was met with a raspy tone that grew coarser and coarser until the climactic high B flat at the close of the evening that the tenor had to cut short because, well, he didn’t have it. One could argue that this raspiness of sound (the tenor was either doing battle with a phlegm or a dry throat during Act three) coupled with the choppier phrasing suited Samson’s broken state. You could almost buy that the vocal difficulties were a part of the characterization, but it became so frequent that it was clear something else was up. It’s a true shame for Alagna because his commitment to the role and performance at hand could never be in doubt and he was undeniably compelling throughout.

As the High Priest, Laurent Naouri went for a more violent and animalistic portrayal, his vocal exploration of the character heavily accented and aggressive. It suited the colder approach employed by Garanča and gave the world vocal contrast. This was furthered by the presence of Dmitry Belosselskiy’s Old Hebrew, whose calmer singing also gave richer counterpoint to the fiery Priest and unsteadiness of Alagna’s Samson.

The Stars of the Night

The stars of the night, however, were the larger ensembles. The Met chorus always seems to be in a world of its own. A good one, that is. From the opening passage, “Dieu! Dieu d’Israël,” the voices rippled as one through the theater with immersive effect. The crescendo throughout this opening passage was captivating, pulling us in deeper and deeper into the suffering of the collective. From the quietest of sounds to the most explosive, we were with the ensemble every step of the way. In the final act, the chorus’ display was just as powerful, the contrasts between pious Hebrews and orgiastic Philistines was quite clear in the sudden shift in sound; this final act featured the chorus vibrant and forceful, each note crackling with rich and bright sound.

The orchestra, under Sir Mark Elder, was in fine form from the opening note to the last. Few things remain as memorable as those sforzando low B’s in the lower strings at the start of the work, the interjections creating a sense of foreboding over the hymn-like nature of the woodwind passages. It was in these opening bars that I knew we were in from a magical evening from the orchestra. The crescendo throughout the opening chorus was palpable, but things really took on another dimension during the second Act’s opening passages, the whirling sextuplet rhythms becoming the lifeblood of the piece. It all came down to the precise and yet seamless melding of instrumental voices in these insistent figures, the passing of musical baton from one to the other impossible to turn your attention away from. The Bacchanal surged with energy and even if the vocal and orchestral ensembles seemed to be performing different measures at the same time during the ensuing prayer to Dagon, it wasn’t enough to derail what had been a mesmerizing evening from the orchestra.

Ultimately, though, one can’t shake off the nagging sense of disappointment that this opening to the season had. After a steady and methodical build-up in the news cycle that expressed the theme of great change, it felt like the Met was poised for an opening night for the ages that would further this theme. But this change was simply not reflected onstage. The takeaway from this production is that the creative heads are still trying to figure out where they’re heading from an aesthetic standpoint with the insistence on traditional productions, dressed up as “modern” and “theatrical,” still the trademark. They look newer and fresher, but they still don’t have much to say. Fortunately, we all know that the performers will only get better with each passing performance as they grow into the roles and the staging, and that should make subsequent performances more interesting and engaging for the viewer.