Tiroler Landestheater Innsbruck 2017 Review – La Gioconda: Elena Mikhailenko Shines In Controversial But Effective Production

By Alan NeilsonAmilcare Ponchielli was unfortunate in being born after his time had passed. Although recognized as a talented composer, he developed a reputation for composing music which always appeared to be a little dated, with the result that his operas have now largely been forgotten and rarely performed, eclipsed by the greater talent of Verdi, and that of his pupils at the Milan Conservatory, Puccini, and Mascagni. His grand opera, “La Gioconda,” composed in the wake of a belated interest in the genre on the Italian peninsula, illustrated this conservative tendency, yet it also highlighted his undoubted talent, for this is a well-crafted opera, full of memorable tunes and dramatic intensity, which in turn has enabled the work to maintain its place in the world’s opera houses. Moreover, it is a work in which we can clearly discern a certain influence on verismo, and the operas of his more illustrious students.

“La Gioconda” is an opera of strong contrasts, both musically and dramatically. Musically, it shifts between periods of intense conflict and tenderness to lighter, entertaining sections, such as the masked ball scene and its accompanying ballet music, the “Dance of the Hours.” Dramatically, it is certainly very dark and bleak, with a tragic ending in which Gioconda commits suicide and her mother is murdered, yet it is played out against the colorful backdrop of 17th century Venice with its canals, its carnival, the songs of the gondoliers and the wonderful sights of the city. There is a lot of material for a director to work with, and allows for a variety of interpretations with its large cast of interesting, if not always fully filled out, characters.

A Darker Outlook

In this production for the Tiroler Landestheater the directors, scene and costume designers, Alexandra Szemerédy and Magdolna Parditka decided to downplay the contrasts and delivered an unremittingly brutal and grim reading of the work. Divertissements and lighter moments were underplayed or given a sinister twist. The ballet scene was imaginatively presented as the dancers mechanically followed Barnaba, the spy cum puppet master, who laughingly and menacingly led them in a contorted and fractured dance, while in an adjacent room Laura was experiencing the violent effects of the drug which was administered to simulate her death, with the help of a little physical abuse from the masked protagonists. The carnival scene at the opening of the first act became a political demonstration with the populace demanding “Bread and Circuses.” Nothing was allowed to distract from the heavy oppression that hung over the drama. All the characters, with the possible exception of Barnaba, who seemed to enjoy the entire experience, were portrayed as miserable, put-upon or emotionally deficient. This was nowhere better exemplified than in the role of Gioconda herself, who was portrayed as a downtrodden and unloved housewife, struggling to look after her blind mother, and who experiences nothing but heartache and strife.

The colorful scenic possibilities of the Palazzo Ducale, Ca d’Oro, the Venetian Lagoon and the views from the Giudecca were abandoned in favor of a nondescript country suffering under a communist dictatorship. The sets comprised of an aggressive-looking structure made from scaffolding, which rotated to reveal a cheap courtroom cum general utility room for dead bodies and other miserable goings-on. Moreover, Szemerédy and Parditka highlighted the oppressive nature of the State, never failing to take advantage of any opportunity to emphasize its tyranny. In Act one, La Cieca is accused of witchcraft, and instead of Alvise and his wife entering and quelling the crowd, as per the libretto, she is dragged in front of the court from which she is eventually released, courtesy of Alvise, who is not just the military leader of the State, but also its supreme judge. In fact, the personal nature of the tyranny is very much to the fore, as Alvise, following Laura’s “death” takes Gioconda, against her will, as his next consort. If all this sounds depressing and depressingly one-paced be assured it was not; this was a dramatically and emotionally gripping piece of theatre, in which the very real themes of State oppression and violence, which lie at the heart of “La Gioconda,” are explored in an imaginative and forceful manner.

A Step Too Far

Nevertheless, questions have to be asked about the degree to which it is acceptable for a production to move away from the limitations imposed by the libretto and its music. Szemerédy and Parditka may well have stuck closely to the themes and the dynamics that drive the drama forward, but in doing so they played fast and loose with the narrative and score. Shifting the setting in time and place is normal for many productions in opera houses throughout the world, and generally considered to be a valid and, in many cases, illuminating exercise. Changing the actual story itself is a step further and not so easily justifiable.

Act four, in particular, came in for some very heavy-handed treatment indeed. According to the libretto, Gioconda stabs herself to death and leaves Barnaba seething that his act of revenge in killing La Cieca was, thus, a pointless deed, as Gioconda dies oblivious to his actions. Szemerédy and Parditka, however, have Enzo stab Gioconda, a wound from which she eventually dies, who herself poisons Barnaba, now her husband (or partner), before being comforted in her death throws by La Cieca, who has not been killed by Barnaba. Dramatically, this created a stronger ending than the original – but it is a long way from what was written!

If this seems somewhat controversial, then changing the score is likely to prove more so. For sure, it is normal to combine various versions of the same work, or to delete parts of the score in order to tighten the dramatic impact, but to actually reprise the opening chorus as a closing chorus, as in this production, is not so usual. Again the dramatic impact was enhanced by this decision, as Alvise alongside his new consort, look out on the people, who are looking forward to more “bread and circuses.” Everything has come full circle, normality has returned. Great theatre maybe, but it does raise questions about the extent to which it is still the work of Ponchielli and his librettist, Arrigo Boito, and of course, whether or not such concerns matter.

Powerful Leads

On the musical side, this was a very strong production, containing no weak links, and some excellent singing performances. Moreover, almost without exception, the singers were excellent singing-actors.

In the title role of Gioconda was the Russian dramatic soprano, Elena Mikhailenko. She produced an intense and expressive performance, underpinned by wonderful vocal control, as the put-upon daughter of La Cieca, and the jilted wife/lover of Enzo. In the first act she is seen looking after her house, her blind mother and her husband, Enzo. It is a thankless task, and through the course of the opera, her life deteriorates as she faces one problem after another, culminating in her death in the final act. Mikhailenko’s performance was truly impressive, managing to uncover the emotional core of the character and convey it wonderfully through some splendid acting and formidable singing. She possesses an array of vocal colors, backed by the ability to inflect the voice with subtle dynamic accents, which she applied intelligently to bring about a convincing portrayal of Gioconda. Her voice is warm and dark in the lower register, bright and steely in the upper register, and powerfully consistent throughout. She negotiates the transition between registers with apparent ease and fluency, losing none of its power or quality in the process. Moreover, everything she did was done with emotional honesty.

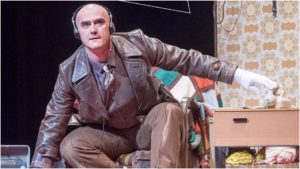

Marian Pop gave a truly mesmerizing acting performance in the role of Barnaba. From his first entrance onto the stage, in which he is seen bugging Gioconda’s phone, he exudes evil, and moreover, he relishes in the fact. He is never far from the heart of the action in one guise or another, whether it be a lawyer, an army captain or a seaman, yet he is always a spy, always intent on destruction. Pop played the part for all it was worth, his every gesture, his every facial expression perfectly placed. He laughed at people’s despair, enjoyed their pain and hated everyone, including Alvise. In Act two, a group of citizens are caught attempting to escape the country on Enzo’s ship. The curtain falls to Barnaba orchestrating their execution. Pop has an accomplished singing technique, which he employed to good effect. His phrasing was always finely measured, with exactly the right amount of venom or irony in the voice.

Viktor Antipenko essayed Enzo as a mentally fragile and self-indulgent individual, willing to act on impulse with little regard to his responsibilities. Although he took a little time to work his way into the role, when he did so he gave a really splendid singing performance, full of passion and emotional intensity. His aria, “Cielo e mar,” was dispatched with a great deal of quality, his voice displaying a warm solidity in the lower register, with an impressive secure upper range. Antipenko infused the role with energy and drive and brought depth to what can be a fairly superficial character

The American dramatic mezzo Jennifer Feinstein put in a fiery performance as Alvise’s wife, Laura. Like Gioconda she is in a loveless marriage, and is therefore, more than happy with Enzo’s arrival on the scene. Her Laura is a feisty woman, more than happy to lock horns with anyone, especially with Gioconda. Feinstein is ideally suited to the role, having an expressive and vibrant mezzo, with a bright powerful high register, yet also a wonderful lower register with dark musty tone. Her commitment and energy were admirable as she battled against formidable opponents in Alvise and Gioconda.

Nuance in Support

Anna Maria Dur gave a nuanced and convincing performance as the blind old mother of Gioconda, La Cieca. The expressive aria “Voce di donna, o d’angelo” in which she thanks Laura for saving her was delivered with great a deal of sensitivity, and emphasized the beautiful timbre of Dur’s voice. It also allowed her to display her excellent vocal control, which culminated in a wonderful pianissimo legato.

Dominic Barberi cut an impressive figure as Alvise. Physically tall and broad, he suited the part perfectly and portrayed the military leader as callous and uncaring. His sexual assault of Gioconda was brutal. He acted out the part well enough, although his voice lacked the power and gravitas to totally convince. Nevertheless, his voice does possess a pleasant timbre and he showed ability in characterization. He would certainly benefit, however, by improving his vocal projection.

However, it was the ensemble pieces, especially the scenes of confrontation, which really set the opera alight, and caused the emotional sparks to fly, producing in the process the evening’s most compelling scenes. Gioconda’s confrontation with her rival, Laura, “L’amo come il fulgor del creato” was possibly the most fiery. Such was the quality of both Mikhailenkos and Feinstein’s voices that they created a scene of the highest quality, in which their clash bristled with electrical energy, that threatened to discharge at any moment.

The Tiroler Symphonieorchester Innsbruck, under the direction of Francesco Rosa, elicited a refined, if occasionally understated reading. Rosa was very considerate to the needs of the singers, possibly overly so, which slightly compromised the orchestral side of the performance. However, in the work’s numerous orchestral passages the ensemble was allowed to blossom and produced a very rich and satisfying sound.

The Chorus Tiroler Landestheater, under the charge of the Chorusmaster Michel Roberge, produced a solid, pleasing performance, if never really hitting the heights.

Overall, this was a wonderfully well-acted and well-sung performance of “La Gioconda,” full of dramatic intensity, which was roundly appreciated by the audience of the Tiroler Landestheater. Whether this can be seen as a result of, or despite the, decisions taken by the directors will probably depend, to large extent, upon one’s view of the scope of the director’s role. Either way, it is a fine production containing some first-class singing.