Teatro Real de Madrid 2020-21 Review: Rusalka

Asmik Grigorian, Karita Mattila Rescue Dvorák’s Masterpiece from Cold, Confused Production

By Mauricio Villa(Credit: Javier del Real)

This review belongs to the third performance of cast A on the 16th of November 2020

After an absence of nearly a hundred years, “Rusalka” returned to the stage of Teatro Real, with a new production directed by Christof Loy in co-production with Säschsische Sttaatsoper Dresden, Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona, and the Palau de Les Arts Reina Sofia in Valencia.

Sublime

Leading the way in the title role was soprano Asmik Grigorian who has great international attention with her interpretations of Salome and Chrysothemis. This young soprano has a voluminous dark voice that maintains a round timbre from her low register up to B flat, gaining in intensity and volume as she rises up the tessitura. Her center is stable and present, something adequate for a role which is written mostly in the middle of the stave.

Her interpretation of the famous “Song to the moon” was delicate and expressive, navigating through the famous melody with easiness and subtly. The final high B flat was immensely resonant and vibrant, although her voice lost some of its roundness as the vibrato widened on the climactic moment. Her singing in Act two is very short as she remains mute throughout ( the mermaid obtains a human form in exchange for losing her voice) but it’s where the most dramatic momentums arrived that she rose to the occasion with her physical performance.

Grigorian was otherwise sublime in her vocal display of dramatism and desperation, coloring with detail the central singing line of the tessitura and with brave attacks on the two B naturals written in the oppure on the score. In the third act, Grigorian deftly portrayed the sorrow and pain of the abandoned heroine, with the highlight of her performances coming during the sorrowful aria “Necitelná vodní moci.” Here, her attention to dynamics and color was exquisite. Her personification of the crippled ballet dancer was incredible. I don’t know if she has a background in Ballet training, but it was very brave of her to dance and move “on pointe,” something which is really hard to do, especially while singing.

Mixed Bags

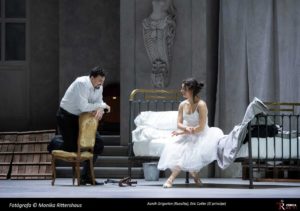

Unfortunately, American tenor Eric Cutler was not at his best as The Prince. It’s also worth mentioning that he had had a medical intervention on his right ankle and rather than canceling his performances he went onstage in crutches, adapting the movements and using extra chairs throughout. I applaud the effort, but do wonder whether the performance was especially hindered by this.

He recently gave an impeccable performance of “Idomeneo” at Teatro Real, but Dvorák’s Prince, with its central writing and sporadic ascensions to A flat and natural (and a high C in act three) and orchestral density, seemed to overwhelm Cutler’s voice, which often sounded distant and far.

Due to his background as a Bel Canto singer earlier in his career, his legato singing was on point throughout his first act aria, but when the music called for more vibrant excitement, coupled with a heavier orchestra, his sound thinned. It was alarming to hear him struggle on the high C in the third Act, especially when considering that Cutler’s high notes are where his sound is most reliable and secure.

Katarina Dalayman sang the witch Jezibaba with strength and determination. She started her career as a soprano, specializing in the Wagnerian and Strauss repertoire, but her big dark voice has settled perfectly into the mezzo-soprano repertory. Here she displayed a big central register, easy sonorous high notes, and fluid legato. She made the most of her two appearances in Act one and three.

Russian bass Maxim Kuzmin-Karavaez sung Vodnik, Rusalka’s father. His role probably has the highest tessitura in the whole opera, navigating constantly between D and E, and with a stratospheric high F sharp in Act two (an extreme note for a bass). He delivered the notes, even if the F sharp sounded forced and strident, but his sound is guttural and small and he, therefore, was mostly overpowered by the orchestra or his colleagues.

Karita Mattila is an opera legend, but her voice tended to be sound worn down in this role. She still maintains an ample high register, proven specifically by the first B flat during her entrance, but the consequent high C was somewhat forced and flat. Nonetheless, she used her formidable stage presence to deliver a robust interpretation of The Princess, reminding us of why she is one of the great opera stars of the past few decades.

Cold & Unengaged

German director Christof Loy presented the masterwork in a cold production. Despite clearly defined stage directing and an elaborated clever concept, his production failed in portraying the magic and passions of Dvorák score.

There is no doubt that Loy is a man of the theatre, so he manages to make everything come alive, with the interaction of the characters and the use of extras and dancers. There is always action happening on the stage. He presented a single set for the three acts, something that has always been his trademark. This time he set the action in the foyer of an opera house, with realistic white marble.

But even if it was aesthetically pleasing, it remained remote. His concept of turning the mermaid who wants to be human into a handicapped ballet dancer with injured feet and crutches distances itself so much from the plot that you feel like you’re watching something completely different.

His choice of turning the gamekeeper and turnspit/kitchen boy into an imitation of Laurent and Hardy did not work because of the huge contrast between their comical exaggerated code of interpretation with the realistic performance of the rest of the cast; this resulted in them turning into absurd clowns.

His choice of turning Rusalka into a ballet dancer was also questionable. It takes years of training to dance on point shoes, so even if I applauded the hard work of the singers, it was hard not to feel that they were anything but poor imitations of dancers as the arches of their feet did not resemble that of a ballet dancer at all, and keeping the legs turned in ( as dancers performed with the legs turned out) all the time, on point or simply standing, did not help at all. It came off as parody in many ways and blatant disrespect to dancers and the hard work they put in. Again, this is not on the singers, who likely have little agency in deciding the concept of the production, but on the director and his choices.

Ultimately, Loy is an extraordinaire clever and talented director, but I believe that this time his work did not help to enhance Dvorák work at all.

Ivor Bolton, Musical Artistic Director of Teatro Real, knew how to transmit Dvorák’s symphonic world by creating dense atmospheres and bringing out multiple colors from the instruments of the orchestra. He worked the harmonic richness of the score, keeping a wonderful balance between all the instruments and the voices. His interpretation was simply brilliant and with the singers, he saved the performance from the production. The brief off-stage appearances from the Teatro Real chorus were solid.