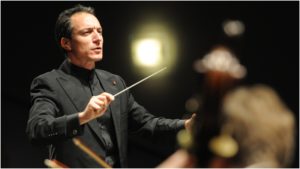

Q & A: Conductor Damian Iorio on Taking on Mussorgsky’s Titanic Masterpiece ‘Boris Godunov’ & The Key To Connecting With Younger Audiences

By David SalazarMussorgsky’s “Boris Godunov” is legendary.

The work is widely regarded as Russia’s greatest opera, even despite its labyrinthine history of revisions.

This week, the work opens at the Opéra de Paris in a production by Ivo van Hove with Ildar Abdrazakov and Alexander Tsymbalyuk sharing the title role. Alongside them will be conductors Vladimir Jurowski and Damian Iorio.

While Jurowski is a veteran interpreter of the famed opera, Iorio is only approaching it for the first time in his career. He kicked off his musical career as a violinist, but spent a great deal of time studying conducting in St. Petersburg before developing a burgeoning international career that has seen him work with such organizations as the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Helikon Opera, Bonn Opera, San Francisco Symphony, Opéra National de Paris, St Petersburg Philharmonic, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, Detroit Symphony, and BBC, among many others.

OperaWire recently spoke with Iorio about taking on the titanic work for the first time and why the time is right for this venture.

OperaWire: Boris Godunov is one of the greatest operas in history. What makes it such a great opera in your mind?

Damian Iorio: ‘History’ is the crucial word in this question. “Boris Godunov” is an important figure in Russian history, as is Pushkin, who wrote the play from which Mussorgsky took the libretto from. With this he is able to bring Godunov to life with incredible vividness. Pushkin and Mussorgsky lead us through his time as Tsar and explore the events and repercussions during an important part of Russian history. This historical canvas displays themes that still resonate strongly with us in the modern day. Mussorgsky had an ability to paint grand musical canvases and express deep emotional feeling through a musical language that was absolutely revolutionary at the time. This technique influenced composers not only in Russia but also composers such as Ravel and Debussy.

OW: What are some of your favorite moments in the work?

OW: There are some very moving moments, but I find the fifth tableau duet between Boris and Shuisky – a duel between two powerful men – and the final death scene particularly powerful. I am always deeply moved at the very end when Boris, on his deathbed, has one last burst of emotion and exclaims “Я царь еще! (“I am still the Tsar!”)” in fortissimo, before succumbing to his death.

OW: When was the first time you encountered the opera and what was your first impression?

DI: I first attended a performance of the second version at the Mariinsky Theatre sometime in the late 90’s when I studied conducting in St Petersburg. I remember being overwhelmed at the time by the sheer breadth and complexity of the opera. Up until then I didn’t know much of Mussorgsky’s music apart from “Night on Bald Mountain” and “Pictures at an Exhibition,” which I had played a few times as a violinist in the Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra where I resided for a number of years. I did realize at the time that it is an opera I would have to approach when I was ready, and now is the right time, as I have matured both as a man and as a musician. After over 20 years of studying and working regularly in Russia, I have an understanding of the country, the people, and the language – a very important aspect of this opera.

OW: The opera’s numerous versions are renowned. Which version will you be tackling for this production?

DI: We are performing the first version of the opera, which at the time was not approved for performance by the Repertory Committee of the Directorate of the Imperial Theatres. However, this version, which Mussorgsky never heard performed, presents us with challenges. Mussorgsky was mostly a self-taught composer and his abilities as an orchestrator were limited. But, with care and understanding, and some tweaking to help put clarity in the music, we are able to perform this incredible music in a way which I hope Mussorgsky would be happy to hear.

OW: Do you have a preference regarding the versions?

DI: I think that the first version, with its starker musical language, and that does not have the Polish act, is incredibly intense in a psychosocial sense. It focuses much more on Boris, his tortured soul, and his decline. It is much darker than the second version and I think that this version speaks more powerfully to us.

OW: What are the greatest challenges of conducting Boris Godunov?

DI: The complexity and depth of the music is very challenging. Every bar has something important to express, and it requires freedom and deep understanding in order to communicate this to the audience. At the same time, it is not music which really needs to be “conducted,” but should be approached like chamber music. Of course, in the big choral scenes the conductor has to be in control to make sure everyone is together. However, a lot of the music is intimate and conversational, so we have worked hard to give the singers the freedom to lead the music rather than being conducted. This version is much more intimate than the second version, but that does not mean that the big moments, the moments of violent explosion, are not impactful. The coronation scene, for example, is one of the most incredibly powerful moments in musical history and is quite an incredible sonic experience. This version concentrates more on the tortured soul of Boris, and his monologue and death are very intimate, which requires a great depth of understanding and expression from the singer, orchestra and conductor. We all have to breathe as one.

OW: What do you hope for from an interpreter of the leading role? You will be working with two different basses of the role. How are their respective approaches to the role different? What unique qualities do each bring?

DI: Boris is one of the great bass roles in the repertoire and requires a singer who is not only mature vocally, but also as a person because it explores the depths of the human soul. Ildar Abdrazakov is an amazing singer and artist who has a wonderful voice and musicianship. This is his role debut and it has been very interesting to see how his understanding of the character has developed and deepened each day. I am certain that he will have big success and will sing this role for many years to come. Alexander Tsembalyuk has already sung Boris many times, providing him with experience and insight into the role. As a result, we are working with him in a very different way to help him adapt to this interpretation of the production. It is interesting working with two singers who have very different voices and different experiences of the role. Both are great singers and musicians who understand the character of Boris.

OW: How does director Ivo van Hove approach the opera?

DI: This production will definitely not be a traditional Boris Godunov with historical imagery of Moscow and the Kremlin. Ivo is drawing parallels with the problems of today’s world, and at the same time focusing on the inner drama of the characters. The production is quite minimalist in order to help the audience concentrate on the internal conflicts rather than the grandeur of the surroundings. I don’t feel that I should go into more detail though as we are still in rehearsal and the production is still developing.

OW: What new insights does he bring that inform your approach to Mussorgsky’s music?

DI: When conducting opera, it is important to be flexible. There are times you might need to support an action on stage by adjusting your interpretation. The timing of a reaction or a movement can be helped by the length of a pause, small adjustment to tempo, or even with the dynamics. The simple act of someone moving from one part of the stage to another has to work with the music, so we might have to adjust something in order to help add to the image and intention that is being expressed. On a broader musical level, we are trying to support Ivo’s ideas about certain situations by adjusting the way we express the music in specific places. It is possible to play a single note in many ways, but again I don’t want to go into too much detail before we open!

OW: Shifting gears a bit, you are also a proponent of programs that bring music to younger audiences. In many countries, opera companies are struggling to connect with younger audiences. What do you think is the key to connecting with these audiences?

DI: This is a very difficult question to answer concisely. Many opera companies are taking great steps to connect with younger audiences and theatres are much more open than ever before. Students and young people are able attend general rehearsals and open days allow the public to see how the theatre works. They’re providing special ticket deals, and even have educational and social projects. However, the lack of music education in schools is where the real problem lies for many countries. At school level there is less and less teaching about music, so children are missing out on something fundamental in their development.

There are places which have well developed and supported projects. My children’s elementary school in Italy is involved in a fantastic project run by an opera theatre which is supported by the region of Lombardy. Each year they study an opera which is adapted for educational purposes and is supported by the outreach department of the theatre. This correlates with a school trip to the theatre to see the adapted version of the opera they have been studying. This means that all of the school children have a connection with music and opera from a young age. More importantly they are exposed to a tradition which is very important in Italian history. In my opinion, this grassroots approach is very important in connecting with younger audiences, but it has to be integrated with general education policy. If we work with schools, then children will grow up having experienced the power of music and understand that a theatre is open for anyone and everyone.

OW: What are some other exciting projects that you have coming up?

DI: My next opera project will be at the beginning of 2019 when I conduct Mozart’s “Magic Flute” at Welsh National Opera. There will be performances not only at the Millennium Centre in Cardiff, Wales, but also on tour throughout the UK. Before that, I have some exciting concerts including Holst’s “The Planets” with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and a tour of South Korea, a country I have never visited before. I also look forward to opening the new season as Music Director of Milton Keynes City Orchestra, that will include some fantastic soloists like the talented young cellist, Sheku Kanneh-Mason, whose name North American readers will recognize from his performance at the Royal Wedding this year.