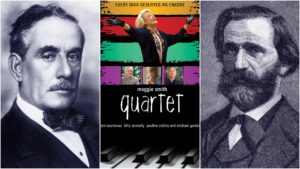

Opera Meets Film: How Puccini & Verdi Aid The Comic & Tragic Meta-Narrative of ‘Quartet’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Dustin Hoffman’s “Quartet.”

There is an old adage about success that goes something like this: “Fake it ‘til you make it.” That is exactly what Dustin Hoffman does with his film “Quartet.”

This is by no means a negative connotation with regard to the film. If anything, it is simply an example of a filmmaker making a specific choice and running with it to the end of the work.

“Quartet” follows the life of retired musicians at Beecham House. It’s chief protagonists are four opera singers who are dealing with issues from their past as they attempt to reconcile and put on a performance of the quartet from “Rigoletto.”

Faking It With Great Fun

The film actually goes to great lengths about the quartet’s importance, emphasizing that it was the four of them that made one of the great “Rigoletto” recordings of the post-war era and it is only fitting that they rejoin forces for one big showcase during a Verdi gala that the Beecham House residents are putting on to save the retirement home for musicians. If anything, this is the film’s chief objective – bring these singers back together so they can help save the fundamental institution.

And this is how Hoffman manages to pull of his big trick. None of his chief actors, Maggie Smith, Tom Courtenay, Bill Connolly and Paulin Collins, are opera singers. And Hoffman never puts them in a position to have to engage with performing at all. Instead, he keeps the audience wondering if they might. We understand the circumstances. They are all older and retired and likely not in great vocal shape. Jean herself has sworn off singing altogether. And yet, we fully believe them as artists and are waiting to hear them open their mouths and perform the piece they repeatedly talk about performing.

They never do. Or at least, not in the way that we expect them to.

When the four finally take the stage to put on their big show, the film draws to an end and instead we hear the quartet performed over the credits. It is a recording featuring Luciano Pavarotti and Joan Sutherland; opera lovers would be privy to this conceit and immediately identify the performers. But the effect is still quite potent. We get what we are waiting for, even if not the way we anticipated. In this manner, Hoffman plays with audience expectations, pulling a big prank on them throughout the entire experience. The fact that the film is a comedy only supports the ultimate effect.

It turns out, in fact, that we don’t actually need to see them sing.

Not Playing Anymore

But there’s more. Hoffman does actually showcase an opera performance on camera. But he does it with a true opera legend, specifically Dame Gwyneth Jones, who plays the character of Anne Langley. The aria of choice? “Vissi d’arte,” which in the context has both obvious and rather complex significance. On one level, Jones’ performance supports, for the audience, the authenticity of the performance and the world of the film one last time. But the aria itself plays on some of the themes of the film.

The text itself is about Tosca noting that she has given her life fully to art, love, and God and doesn’t understand why she must thus be forced to suffer despite her own good works. The aria itself, despite being full of so much suffering and pleading, is also truly cathartic and uplifting out of context.

It encapsulates the film at large with those living for art finding their own future hanging in the balance. The aria then becomes a plea for the people in the audience to recognize that these retired artists cannot simply be cast off. They have done a world of good through their art and now they are imploring that their home be saved.

It is worth noting how fascinating it is to find this particular aria as a counterpoint to the film at large. A story about how an older generation is being cast off and thrown out of their homes is presented as a big comedy with the dialogue and numerous scenes full of subtle but effect hijinks. The quartet from “Rigoletto” hangs over the proceedings as a “musical ghost” if you will with the audience constantly anticipating its performance. And while that piece comes from a tragedy, it is a deliciously melodic number in major key.

But for Hoffman to suddenly shift the tone and display one of the more tragic arias in the repertory is itself an effect counterpoint for the film and an emotional way to reveal the dark and hidden subtext that lurks throughout the story. Displacement of those that have already given so much and should be allowed to enjoy their final days is unfair. That they are forced to fend for themselves at the end of their lives is truly brutal. The characters all do it in jest and the film’s overall tone and conclusion is sunny; but this inclusion is a subtle interruption that lends essential commentary to the situation despite its overall presentation.