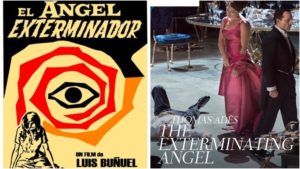

Opera Meets Film: Comparing the Humanistic Views of Buñuel & Adès’ ‘The Exterminating Angel’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features the classic “The Exterminating Angel.”

For this week’s series, we are going to move in a slightly different direction. In past installments, we’ve reflected on the way that opera appears within the cinematic media and how it informs us on character and story.

But there is a major event taking place in the opera world at the moment that is impossible to ignore outright – Thomas Adès’ “The Exterminating Angel.”

Based on the film by Luis Buñuel, the opera essentially represents a straight adaptation in so many ways. The general plotline remains intact, save for the ending. And yet, the opera and its current staging at the Met preserve the theme of perpetuated psychological prisons in society.

But what is interesting about seeing a film adapted into an opera, is that it provides us an ample opportunity to see how the two artforms contrast in expressing similar ideas. And that is the purpose of this piece.

Buñuel’s black and white cinematography provides a rather ample starting point, the director’s imagery elegant and straightforward in its style, expressing the upper class of its main characters. As the film unravels, and so do its protagonists, Buñuel’s pristine visual style strikes a tone of irony; these supposedly refined individuals are not quite what they seem and at their most desperate, certainly, reveal a more vicious underbelly. Animals are littered throughout the film, from a bear hiding in one bedroom, to the flock of sheep that end the movie, underscoring this idea that humans are animals despite our own belief that our reason gives us more moral and natural authority.

Now let’s compare this with how Adès portrays his characters through his music. From the get-go, we hear musical repetition from characters, we hear Leticia Maynar enter with a high A above high C and remain in a vocal stratosphere that essentially characterizes many of the female voices throughout. Vocal lines are generally frayed and chaotic; comfortable melodies aren’t something that we come to recognize in the early going of the opera. If anything, Adès’ music is wild, unhinged, and animalistic. The composer, unlike the filmmaker, is making no qualms about his characters and the way he views them.

Contrast that with their development as the night proceeds. Buñuel preys on the absurdity of the situation, the characters becoming more predatory in nature, the way they are represented visually through their wardrobe and makeup showing them as beasts. Adès’ narrative follows the same line, but the characters grow more human in how they are portrayed. We get a lyrical lullaby of a desperate mother. The two lovers, Béatriz and Eduardo, who commit suicide in rather strange and ultimately unceremonious circumstances in the film, get a love duet in the opera, allowing the audience an opportunity to connect with their love and even justify their need to die together in this prison.

Finally, Leticia, who resolves the entire mess, gets deeper humanization through her identity as an opera singer. At the start of the opera, she is asked to sing, but ultimately opts out and the entire experience begins for its characters. But when the characters get a second chance to relive the events of the first night to free themselves, she does sing. The aria she gets from Adès soars with lyricism in a way that we are not able to hear from the character. Instead of the vicious and rhythmic high notes that we hear from the get-go, the high range here is connected by flowing legato. She too has been given an added dimension.

As the audience connects with the characters on the opera stage in a more humane manner as the night progresses, the ending, which hints at continued psychological torture, becomes all the more tragic. In contrast, Buñuel’s similar ending doesn’t quite leave us with that same sense of loss; the irony and absurdity reign deeper in our understanding of his story. We might even smile.