Hungarian State Opera New York Tour 2018 Review: Bánk Bán

Levente Molnár’s Brilliance Makes Case For Hungary’s Beloved Masterpiece

By David SalazarFerenc Erkel’s “Bánk Bán,” which took the stage at the David H. Koch Theater on Saturday, Nov. 3, 2018, as part of the Hungarian State Opera’s New York Tour, is a fascinating study in the operatic canon.

For Hungarians, Erkel’s piece is their national opera. Outside of the country, it would be surprising to find many that have heard it live. And yet it is a work, that despite being nationalist theater, would probably have a greater claim to a place in the opera canon than many of the other works that are currently being postulated for such a spot.

Bel Canto & Shakespearean Influences

The opera premiered in 1861 when Verdi, Wagner, and Meyerbeer were the kings of opera. And while Erkel undeniably has his own style throughout the work, there is no doubt that in many ways, he is indebted to these two giants and their compositional styles. For “Bánk Bࣙán” is a Shakespearean tragedy in the Bel Canto style with orchestration that takes from the French Grand Opera style.

There’s a drinking song. There’s a mad scene. There are multiple pezzi concertati. There are arias, an ode to Hungary, and other such musical arrangements that would make it a cousin to any Bel Canto opera. But at the same time, we see some musical set pieces that are without the same structural limitations of that operatic style; the duets between the titular character and the queen or his wife are such examples of music drama that seems to borrow from what Wagner had on his mind.

Dramatically, this is a mix of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” with modern-day politics. Something’s amiss in Hungary. While the King is away fighting for his country’s freedom, the Queen has turned the royal court into a circus. She has no care for anything but her own image and power and to this effect, she is willing to step on anyone to get her whims. So when her brother decides that he wants to seduce and ultimately rape Melinda, Bánk Bán’s pure and loyal wife, she has no problem supporting him in the endeavor.

Meanwhile, the titular character is kind of confused about what he is supposed to do. He’s fighting for his country but sees it destroying itself all over. Whose side should he be on? Moreover, he finds out that his wife has been raped and now his loyalty really comes into question. Unlike most heroes and men of 19th-century dramas who would blame the woman for her loose manners, Bánk actually doesn’t condemn his wife and even sets out a course to continue living a familial life by her side.

Instead, he exacts revenge on the queen, but then finds his wife dead; Melinda’s trauma from the event is so great that she not only goes mad and kills herself, but she also kills their own child. Faced with total disgrace, Bánk sees no future for himself and also does away with his life.

It’s pretty tragic, but Erkel’s music manages to guide us beautifully through the opera’s sound world. The opening prelude, despite its repetitive nature, also creates a sense of being lost and isolated, much in the way that the eponymous character will feel throughout the story.

Melinda’s music, angelic and pure in the opening scenes, becomes more and more erratic in its vocal line, asking the soprano to jump from lows to high in rather challenging manner; it’s a voice-killer for any coloratura soprano.

Bánk was originally scored for a tenor, but the baritone role transposition has become far more popular. The darker hue suits the vocal line quite prominently, though Erkel does challenge the interpreter with all of his vocal resources, pushing into the upper register quite often.

All of this to say that “Bánk Bán” is a fascinating work that could undeniably find a sturdy place in the operatic canon if given that opportunity.

Mixed Direction

Unfortunately, the production, as directed by Attila Vidnyánszky wasn’t quite as riveting as the work itself. The program notes explain that the director placed a number of actions that were absent from the libretto but a part of the original source material, the play by József Katona. So to that effect, the villainous Biberach (an underdeveloped Iago type) gets his comeuppance, for example.

But other such elements, like showing another woman who Prince Otté had previously seduced, don’t necessarily add to the drama. We already feel that Ottó is a menace from the way he follows Melinda around. Having another woman following him around and suffer at being rejected by him doesn’t necessarily make us feel his villainy any more or less, especially given the times we live in.

Vidnyánszky seemed a bit anxious to have people just stand around and at times had actions taking place that were peripheral to the central action. Biberach’s murder happens while Bánk is engaged with another issue altogether. The rape itself disrupts from another duet taking place. While it layers the drama, it also confuses the audience; the music is telling us to pay attention to the two singers, but the director wants us to shift our focus to the rape that just clearly happened backstage. The result is that we potentially lose information from the two characters at the forefront of the drama.

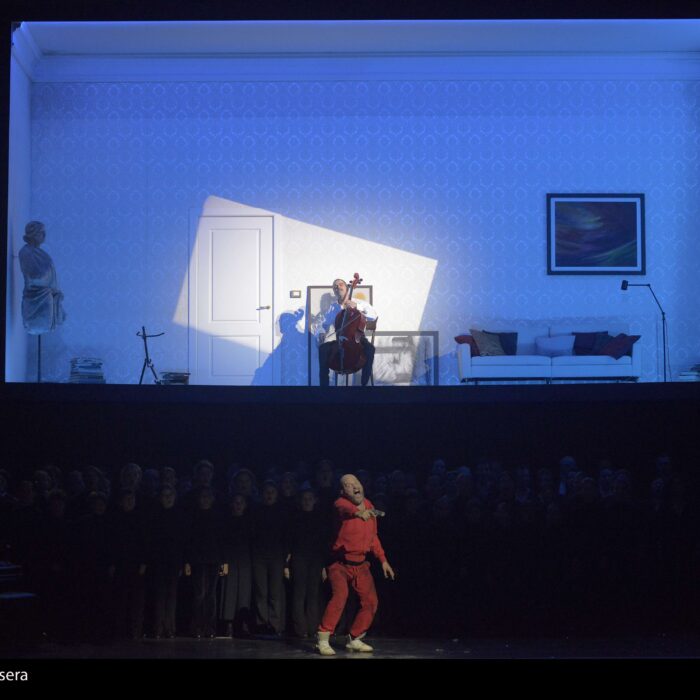

The set itself features two massive walls on either side of the stage with a large awning on which background action frequently takes place. There’s a pole with directions on it on one side of the stage and the “throne” on the other side. A large glass comes up and down at times to create a sense of separation, but on the whole, the set doesn’t feel like it is really doing more than giving us something to look at. The characters interact with it for sure and there are even hints that Bánk has so much power that he can take down both structures (he throws down the pole and at times shook the stage right wall), but on the whole, they don’t add much.

Of course, one of the challenges is that this production was not intended for this theater and one look over at the video recorded of the production in Budapest reveals a very different look and feel that includes lighting effects that were largely absent from the New York showcase. These choices add to the effect noted by the director in the program notes of the title character’s challenges in his public and private life.

I’ll make reference to the “Hamlet” moment (Bánk Bán looks at a skull in the classic “Hamlet” pose) only to note that it looked more like a director not trusting the quality of his source material enough to tell its own story; a reference to Shakespeare doesn’t make it any more or less like “Hamlet” in the viewers’ eyes, but forces unnecessary comparisons of quality.

Costumes looked as if they were aimed at being a mix of period aesthetic with something more modern, which hinted at a sense of timeliness in the story.

Performances were strong throughout, but ultimately, the visual aspect of the production didn’t really create much of an impact emotionally. The result was that the singers were given greater responsibility to explore the story through their singing.

One Hero Above All

This is where we talk about the David H. Koch Theater.

For whatever reason, the singers struggled the entire night with projecting into the hall from the center of the stage. The only place where they had any real chance was by standing on the two wings at the extremes of the stage. And so they did, again and again throughout the night. It didn’t ever seem to be an inspired directorial choice, but more of an essential one for vocal projection.

The only artist who never resorted to this, because he didn’t have to, was baritone Levente Molnár. From his opening aria, his voice was present, potent, and secure technically. His opening aria, in which the character sings of his beloved Melinda, was delivered with a gentle line, the tone in half voice at times, exploring the pure love and pain of the character. This contrasted with the ensuing duet with Biberbach where his anguish was explored through resonant sound and power.

The famed number, “My Homeland, My Homeland,” drew the greatest applause of the night as Molnár’s voice built up the melody, first from a mezzo piano sound to a full-blooded forte by its end. In his higher range, his vibrato retained a tautness and the quality a leanness that was resonated powerfully in the hall.

Physically, he unraveled more and more, the character’s violent edge giving way to similarly jagged singing. His confrontation with the queen featured Molnár’s most unhinged vocal approach, his sound harsher and his phrasing more disconnected. That isn’t to say there was no technical control, because it was evident that the intention was to paint a strong picture of the violent Bánk at his most desperate. Molnár was completely successful in this aim.

It also contrasted with the gentler singing of his previous scene with Melinda and ultimately the hushed tones he utilized in parts of the opera’s ending when all was lost.

Great Highs

Soprano Zita Szemere did a solid job overall with the treacherous role of Melinda. Her highs were quite punchy and bright, really taking flight in the opening concertato where Melinda is tasked with singing some sublime phrases over a massive choral ensemble. It was beautiful to be sure.

But then her vocal quality became erratic throughout the rest of the evening, mainly because her voice tended toward unevenness in its middle and lower registers, the sound rather bare and delicate. This was most noticeable in the second-act aria where she implores Bánk to kill her. Here, the soprano constantly moves from the middle and low into a quick high note and back. It’s undeniably tricky for any singer and it proved particularly challenging for Szemere whose phrasing was choppy. The result was that this painful exploration of grief and guilt didn’t quite hit the mark emotionally.

The soprano sounded far more at ease in the ensuing duet with Bánk, which allowed for their moment of embrace and unity to flourish. Her mad scene was quite effective overall, particularly in her higher range where her coloratura soared brightly. But again, her weaker middle range limited her ability not only to project in the theater but also express deeper emotions about the character’s grief.

A Big Mix

As Bánk’s friend Tiborc, István Rácz showcased a splendid baritone with weight and heft; the duet with Bánk was one of the true vocal highlights of the evening from an ensemble perspective. The two matched one another phrase for phrase, emphasizing the sense of friendship.

As the king, Bass-baritone Marcell Bakonyi had a solid night, though he didn’t get off to the strongest of starts. His voice sounded rather brittle and small in size during his first scene and even when he stood at the wing on stage right, he didn’t project much; as the power figure in the story, he came off as weak. But he recovered nicely a few scenes later for the end of the opera, his sound rounder, the vibrato sturdier, and the phrasing far more direct and crisper.

Tenor István Horváth had an uneven display as the villainous Ottó. He added what seemed like a conscience to the character at one point, making Ottó look undecided about taking the poison that will make Melina fall asleep beside him. But otherwise, he looked like a man on a mission to seduce the weak Melinda. Vocally, his sound didn’t quite resonate at any point in the hall and his ascent into high notes sounded pushed, the sound never blooming at the top. This was particularly noticeable on the high A on “Rám a kéj mosolyg va vár” in Act one when he does his best to coerce Melinda before Bánk’s arrival.

Judit Németh’s voice is rather hard-edged, the vibrato wobbly and the projection jagged. And while it wasn’t aurally pleasing, it suited the villainous and corrupt nature of the character quite well. The same could be said for Antal Cseh’s raspy sound as the evil Biberach.

Powerful Ensemble

The orchestra gave a refined account of the opera under the baton of Balázs Kocsár. The maestro seemed well-aware of the acoustical challenges from his soloists and adjusted accordingly; there never seemed a moment where he covered them or overpowered them. Of course, this made for a muted effect in some moments, though the music really comes alive when Bánk is onstage. Fortunately, in Molnár, Kocsár had an artist that could handle greater orchestral forces and the sound really took off in these moments.

Props must be given to the principal violist Veronika Botos who came onstage for the viola solo that accompanies Bánk and Melinda’s scene together. First off, it’s wonderful to hear this gorgeous instrument get a moment like that one, but another altogether to hear it spun with elegance and refinement of tone. Next, to Molnár, Botos might have delivered the most memorable moment of the evening.

The chorus also put in a solid shift throughout the evening, providing a nice foundation of sound onto which the soloists could soar. It didn’t always work for the soloists, but this could not be blamed on the chorus, which was consistent throughout.

When will “Bánk Bán” return to New York? Who knows. But it is wonderful that New York audiences got a chance to experience this overlooked opera at least once.