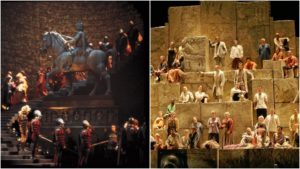

How Verdi Firmly Established His Ever-Evolving Style in ‘Nabucco’ & ‘Ernani’

By David SalazarOn March 9, 1842, Verdi scored his first major success with his opera “Nabucco.” Two years later, on March 9, 1844, the composer scored another riveting success with the world premiere of his “Ernani.” While the respective journeys of these two works have diverged over the one-hundred plus years since their respective debuts (“Nabucco” is a cornerstone of the repertoire while “Ernani” is only sung when major singers want to take it on), both works are widely recognized as crucial early gems in the composer’s oeuvre.

“Nabucco” was Verdi’s third opera while “Ernani,” his fifth. In between them is “I Lombardi,” an admirable work in its own right, but far from the more robust operas sandwiched around it. What is perhaps most crucial about the two operas is how they hinted at the genius to come, which would yet be realized after another dozen or so operas and beyond. Here are some of the features from these two operas that would come to define Verdi’s style over the long haul.

Chorus, Chorus, Chorus

The chorus was a prevalent element in the bel canto style but, with the sole exception of Rossini’s “Guillaume Tell,” it had never played as crucial a role as it did in “Nabucco.” Obviously “Va Pensiero” remains arguably the most remarkable choral music ever written for opera, but the drama revolves around the chorus, essentially making it a character in and of itself. Few other operas have managed the feat since, not even Verdi himself. But it was a major aspect of his work throughout his career and it all started with Nabucco.

A New Kind of Singer

In “Nabucco” Verdi seemed to finally find the voice that would become his and only his – the baritone. Simply put, Verdi’s baritone is a unique vocal phenomenon that no other composer since his time has quite figured out. “Nabucco” was the very first opera to employ this type of singer with a range stretching into the bass’ range and rising up into a particularly high tessitura. In “Ernani” we would see the evolution of this voice in the role of Don Carlo, showing us the grasp that Verdi had on this kind of voice.

Another New Kind of Singer

But that was not the only voice that Verdi discovered in these two operas. The second was of course the famous Verdi tenor, a voice more robust than that of the Bel Canto or French tradition, but retaining the flexibility of those iterations. In his first two operas, “Oberto” and “Un Giorno di Regno,” the composer stuck close to bel canto tradition. The tenor role in “Nabucco,” Ismaele, seems to hint at the type of tenor that would be prevalent in Verdi’s opera, but his role is limited, the vocal capabilities somewhat limited. We get more in “I Lombardi,” though the composer employs two distinct tenors for Arvino and Oronte. Oronte is the part that hues closer to the true Verdi tenor and gets the more popular tunes, but Arvino, a more lyric tenor, plays a more crucial role in the overall drama.

It is with “Ernani” that we finally get the true Verdi tenor in all of his glory, the tessitura established and the use of the voice essentially fixed for the composer. We would hear this kind of tenor in dozens and dozens of operas to follow.

Dramatic Form Through Ensemble

Verdi’s solo numbers for singers are remarkable and throughout his career he created a plethora of iconic arias that remain fixtures outside of their operatic contexts. But what is perhaps most remarkable about his dramatic output, is his ensemble writing. Few other composers before or after (with the exception of Mozart) were quite as brilliant at crafting an ensemble that expressed differing dramatic feelings simultaneously. We start to see those things in “Nabucco” and especially in “Ernani.” “Nabucco’s” grand duet between the titular character and Abigaile is a fascinating combination of conflicting emotions and power dynamics, the composer jumping from one emotional extreme to another without flinching. His ability to push the form and blend it at ease is also fascinating. Let’s be clear though. Verdi was not revolutionizing operatic form the way Wagner eventually did, but he was pushing its boundaries, blending double arias so they would remain continuous, giving the drama a greater cohesion.

“Ernani” also continues this experimentation with the final scene, the greatest musical-dramatic triumph of its time. Verdi’s scene starts with a brief duet that is cut off by a leitmotif figure, shifting the drama from bliss to foreboding. Then another brief scene follows with the tenor getting a brief solo number that approximates an aria. That too is cut off by Silva, the dialogue pushing toward its climax. But just when fate is almost sealed we get yet another interruption, this time by Elvira’s high note, launching us into a more “formal” trio. That leads right into the work’s tragic end. It moves at breakneck speed, one of the composer’s trademarks, because of his ability to play with form and combine it into brilliant dramatic ensemble.

We would see more refined examples in later operas such as “Rigoletto’s” Quartet, “Traviata’s” Act 2 duet between Germont and Violetta, the duets in “Forza del Destino,” the love duet in “Un Ballo in Maschera,” the quartet in “Don Carlo,” the concertato in “Otello” and the entirety of “Falstaff” among many other exquisite examples.